At the back of the classroom, a boy sits quietly, his gaze fixed on his notebook. His peers see him as just another Carlmont student. What they don’t see are the words swimming on the page, twisting and fading as his dyslexia challenges his comprehension of every sentence.

Students with “silent” disabilities, those that are not outwardly obvious, overcome challenges that many other students do not face. Living with a silent disability such as dyslexia, other learning differences, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or social anxiety means facing unique challenges, sometimes with the help of special resources. While these disabilities may be difficult for others to see, their impact on students’ lives is often profound, impacting academic performance, social interactions, or mental health.

According to the Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease, as of 2024, approximately 133 million Americans, nearly 45% of the population, live with at least one chronic disease, and more than one in five experience a mental illness. In addition, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), approximately 15% to 20% of the global population exhibits some form of neurodivergence, defined as people whose brains process information in unique ways compared to others. Neurodivergence is not a medical condition; however, it can be associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and learning disabilities.

These statistics highlight the high prevalence of silent disabilities. For some of these individuals, these challenges can lead to daily feelings of loneliness as they struggle in silence, misunderstood by peers and teachers. The lack of visible signs of these conditions may make it harder to find support, understanding, and inclusive environments.

Impacts on schoolwork

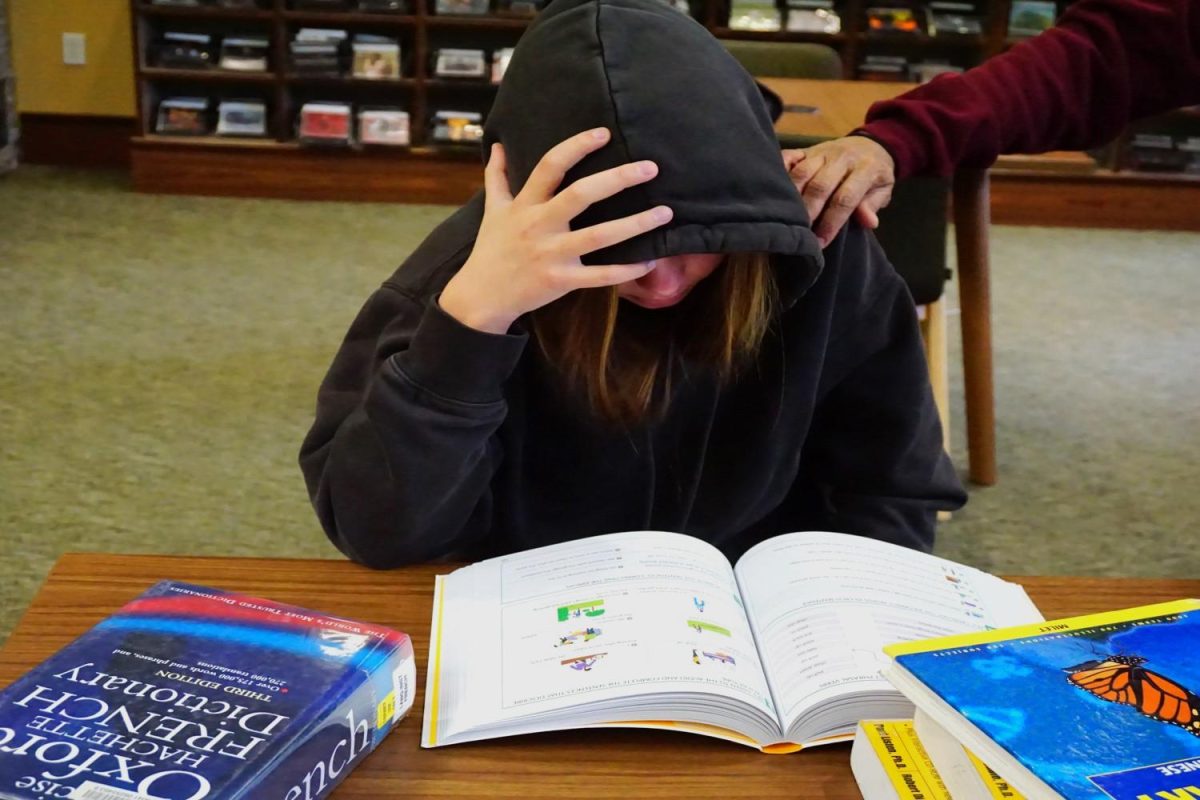

For students with silent disabilities, the challenges of classwork often go unnoticed. Days may be filled with tasks that seem straightforward to others but require immense effort from those with learning differences or mental health challenges. The effort to complete assignments, stay focused in class, or keep up with fast-paced lessons can become overwhelming.

“It takes longer for me to complete assignments, and the more time I take, I’m falling even further behind,” said Carlmont student Hanna Thatcher*, a student who is in special classes for her learning differences.

In the classroom, where focus and comprehension are required, some silent disabilities can turn even routine lessons into significant hurdles. Students may find themselves unable to process information quickly when it is presented, leaving gaps in their understanding.

“My forgetfulness is especially prominent in classes like English and world history, especially if the teacher talks fast or there are a lot of things packed into a lesson for the day, so they have to go fast, which doesn’t give me a lot a lot of time to process the information,” said Trey Cardona*, a student who has learning and social challenges.

These moments can accumulate into larger struggles. Tests and quizzes meant to measure knowledge can instead highlight learning obstacles that these students face.

“It’s like I’ve worked long hours, but I can never really set time for myself to relax,” Thatcher said.

The constant effort leaves her feeling drained, both mentally and emotionally, and can impact her performance on class-based timed examinations.

Group projects can also be difficult for those with silent disabilities.

“I am not a very social person. So just having group work is a bit more difficult, and I usually prefer alone projects,” Cardona said.

Even the structure of the school day can feel unforgiving. Long periods of concentration, fast-paced lessons, and the pressure to meet deadlines amplify the difficulties for these students.

“Sometimes I’m so tired that I can’t focus,” Thatcher said. “These are days I kind of close my eyes and can’t keep up.”

Local experts suggest that some of these disabilities have become more prominent over the last few years.

“Postpandemic, it’s my experience that many students experience lingering social-emotional difficulties,” said Racquel Walker, the school psychologist at Carlmont.

“Emotional disabilities have led to a significant uptick in school referrals, and while some adults believe that life is back to normal and that the effects of the pandemic are behind us, I challenge this concept when I see students who were once thriving socially, physically, and academically before the pandemic now just trying to get by,” Walker said.

Social barriers

For some students with silent disabilities, simple social interactions, like joining friends at lunch, can feel exhausting. While others may chat effortlessly and share laughs, some of these students struggle to fit in and may feel lonely and alienated.

“I’ve struggled a lot with talking to other people, like having conversations and knowing what to say at the right time,” Thatcher said.

For others, the hardest part is not being able to understand why they feel the way they do.

“It’s starting to really deteriorate my mental health, and I’m trying to figure out why this is,” Thatcher said.

Resources and solutions

Schools like Carlmont High School provide a number of interventions designed to help these students succeed. Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and 504 plans are two methods by which schools offer tailored accommodations, aiming to create a more accessible learning environment for those with challenges.

IEPs provide personalized goals and accommodations for students who qualify for special education services. These might include extended time on assignments, access to written notes, or preferential seating to help reduce distractions. The California legislature has developed recommendations around best practices for the development of these plans.

Over 200 students at Carlmont currently have IEPs, and these plans are highly individualized, according to Grant Steunenberg, a vice principal at Carlmont.

“The specific accommodations are going to depend on the decisions made in an IEP team meeting or a 504 team meeting,” Steunenberg said.

Similarly, 504 plans provide adjustments for students who may need accommodations while in a regular classroom, with the goal of allowing equal access to educational opportunities for these students.

About 14% of students at Carlmont have 504 plans, according to Anh Truong, the Carlmont Intervention Counselor who manages the 504 program. Nationally, around 2.5% of all high school students have a 504 plan according to the U.S. Department of Education.

“Students are always included in meetings to share how their disability affects them in the classroom,” Truong said. “Based on the impact and needs the student has, we tailor each accommodation to support them.”

Teachers work proactively to ensure students receive the help they need.

“Most of the accommodations are just automatic in the classrooms,” Steunenberg said.

Some of these students need to advocate for themselves when utilizing these resources. For example, if a student requires extra time on an assignment, they may need to approach their teacher in advance.

“You have to talk to the teacher ahead of time and say, ‘I need extra time on the assignment,’ and the teacher would be like, ‘You got it,’” Steunenberg said.

Carlmont High School offers a variety of other programs designed to support students with diverse needs, including those with silent disabilities. These programs go beyond just providing accommodations, but also create spaces where students can feel understood and capable, while focusing on their emotional and social development.

The Social Academic Class (SAC) focuses on helping students who struggle with social interactions and communication. SAC acknowledges how daunting social situations can feel for some students, providing them with tools and practice to build confidence.

“The class teaches students how to have social interactions and gives them a chance to practice these strategies,” Steunenberg said.

Carlmont’s Associated Student Body (ASB) also plays a role in supporting these students through its Reach Out commission, which organizes inclusive activities such as dances and social events to help students who sometimes struggle with socialization.

For students facing emotional challenges, Carlmont also offers the Successful Transition Achieved with Responsive Support (STARS) program, which provides a small group supportive learning environment tailored to an individual student’s emotional needs.

The dedication of teachers and staff plays a vital role in students’ success in these programs. Justine Hedlund, a teacher in the SAC program and a board-certified behavior analyst, explained how her dual expertise helps her students.

“I’m able to use a lot of strategies from my other degree, using a variety of positive behavior reinforcement systems,” Hedlund said.

In her classroom, students have access to unique tools like wobble chairs, stand-up desks, and fidget spinners which support focus and comfort.

Hedlund also emphasized the flexibility of her classroom design.

“We don’t have to align to specific standards or a curriculum, and we get to address directly what our students are struggling with day to day,” Hedlund said.

Support through understanding

These programs all offer a glimpse into the often unseen challenges faced by students with silent disabilities and the myriad of solutions that schools can provide.

The quiet student in the corner or the one who hesitates to raise their hand or avoids the crowded lunch table may be dealing with their own differences. Only when others understand the weight these students carry can we begin to create a world where they are no longer invisible.

“Everybody faces their own struggles,” Thatcher said. “Personally, for me, it can have a really big impact on my life, but it is better when everybody realizes that we all have our own strengths.”

*These sources’ names are changed to protect them from emotional harm. For more information on Carlmont Media’s anonymous sourcing, check out Scot Scoop’s Anonymous Sourcing Policy

This story was originally published on Scot Scoop News on January 31, 2025.