Whether in the hallways, at a bus stop or at a grocery store, one sight is almost guaranteed: teenagers sporting a pair of headphones, listening to music. With a plethora of platforms to choose from and 6,000 genres on Spotify alone, listeners have more options now than ever before.

Coinciding with music availability has come a surge in time spent listening. A study by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry reveals the average person listens to 20.7 hours of music weekly, or roughly three hours per day. Some students, like Derick Doresca ’26, choose to listen because of comfort and habit.

“[Music] helps me get in the right state of mind. It helps me relax, especially if I’m really stressed out,” Doresca said. “I can’t do homework without music. I spend a lot of time [playing] music, so when I’m doing other stuff, I like to be listening to music.”

Like Doresca, an estimated 55% of high school students across the United States listen to music while studying. Though research has repeatedly shown that the human brain cannot effectively multitask, a study by the Association for Psychological Science introduced selectively dividing attention, meaning that, by remaining selective and intentional with music choice while studying, listening to music has little to no negative impacts on human cognition.

West psychology teacher Camille Crossett explains that music’s effect on learning depends on the listener’s environment.

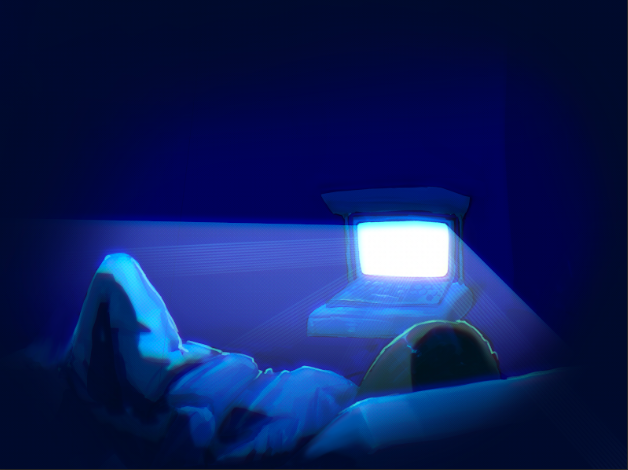

“If you learn in the same environment as you take a test in, you can generally expect better results than if you were learning in a wildly different context,” Crossett said. “For instance, if you were to study at home, laying down on your bed, playing music and multitasking, you probably won’t do as well on that task. You’ll have a harder time recalling information than if you were to study sitting at a desk in a quiet environment, the environment that you might be tested in.”

This phenomenon is known as context-dependent memory, which relies on external surroundings to trigger memory retrieval. Working parallel with this is state-dependent memory, which alters memory retrieval based on one’s emotional and physical state; for example, if an individual’s mood during testing matches that of studying, they will likely have better recall.

While many harbor concerns about remaining productive when listening to music, studies indicate that music increases neuroplasticity, which promotes productivity. Abbey Dvorak, an Associate Professor of Music Therapy at the University of Iowa, explains the connection between listening and the brain’s retention of information.

“Music can enhance brain neuroplasticity, [which] is the process in which our brain makes new connections and it prunes old connections. [Music is] a rhythmic auditory stimulus that can synchronize neural firing in our brains,” Dvorak said. “Neurons that fire together wire together, so it strengthens our learning and our connection to music.”

Music’s effect on neurological functions isn’t limited to neuroplasticity — research indicates that music releases neurotransmitters into the brain’s frontal lobe that evoke positive emotions.

“We know the alphabet by the time we’re two; it’s because we put it into a song, and we remember the song because it’s engaging. Dopamine is released [because] it’s rhythmic, so our neurons are firing,” Dvorak said. “[Children] want to sing it over and over again. The repetition piece is there, which also enhances our long-term memory.”

Aside from improving recall, music-evoked nostalgia stems from the hippocampus and provides emotional comfort to listeners.

“Familiar music can be associated with positive memories of pleasant experiences, so when we hear a piece of music on the radio, we might think back to that wonderful time in our life,” Dvorak said. “Many older adults reminisce with music this way, and even younger generations can enjoy music because the lyrics of music pieces might have positive messages or positive associations that help us feel better.”

On Dec. 4, 2024, Spotify released Spotify Wrapped, a comprehensive list of individual listening time and artist preferences. With over 147,000 minutes of streaming on Spotify, Flora Zhu ’25 understands the importance of having an emotional connection to music. Zhu listens to music to not only uplift her mood but also bring back nostalgic memories.

“One song I’ve listened to for a long time is ‘Everything Goes On’ by Porter Robinson,” Zhu said. “I’ve been listening to it since ninth grade, and it’s one of my top songs. It’s been there throughout my whole high school journey, so it represents my adolescence.”

However, neurotransmitters can also stimulate negative emotions. Though sad songs can serve as emotional outlets, listening to sad music repeatedly can worsen one’s emotional state instead of improving it. Coupled with the winter season, negative music is shown to perpetuate Seasonal Affective Disorder, commonly referred to as seasonal depression, among listeners. To combat an excess of negative emotions, Zhu recommends that listeners oscillate between consuming sad and uplifting music.

“When you like a sad song, it’s because that song is something you can relate to. For example, if an artist wrote a song about breaking up with their boyfriend, you [might] listen to it because it’s relatable,” Zhu said. “That’s fine, but at some point, you also need to find other music that makes you happy.”

Dvorak echoes Zhu, reminding listeners to remain mindful of their music consumption.

“It’s okay to listen to a sad song, and it’s okay to use the Iso-principle, which is [when] you match [your] mood and the mood state of that song,” Dvorak said. “But slowly try to listen to music that gets you out of that stuck state, until you’re feeling the way you want to feel.”

According to Tallahassee Memorial Health, the Iso-principle can be an emotional coping mechanism, while simultaneously improving moods with increased dopamine production. Doresca employs this tactic, using it to identify and enhance his emotions.

“If I’m down, I [have] one playlist that has more slow songs; say I’m working out and trying to get hyped, then I have another playlist for that — it’s different depending on my mood,” Doresca said.

Not only does Doresca listen to music; he also performs it, playing the drum set in West’s Jazz Ensemble and other percussion instruments in the Wind Ensemble. According to Penn Medicine, playing instruments involve multiple sensory inputs — visual, auditory and emotional — that require complete focus. Due to the amount of concentration necessary, Dvorak believes that playing music increases mindfulness.

“By playing an instrument, singing or dancing, we can be fully engaged, attentive, aware [and] non-judgmental,” Dvorak said. “The whole music experience itself is our focus, and in that way, we can be very mindful as well.”

Because musicians require complete focus in such music, Zhu, who is a violinist and pianist, finds that listening to classical music while studying is often distracting.

“[Listening to classical music] is a totally different experience than listening to pop music because I’m a classical musician,” Zhu said. “When I’m playing music, I have to be more absorbed in it because I’m trying to convey that to someone else. But when I’m listening to pop music, the artist conveys that feeling to me through their lyrics.”

While musicians may be prone to distraction when listening to a certain genre of music, others may not be — so what genre can music listeners consume without distraction? According to John Aiello, an Emeritus Professor at Rutgers University’s Department of Psychology, music distraction varies across listeners.

“It depends on who you are because there’s no one-size-fits-all answer to how music influences task performance,” Aiello said. “That’s why it’s such an intriguing question, because it’s one of those situations where you have to know the person to know how music is going to affect them.”

In 2019, Aiello conducted research revealing that music’s effect on cognitive task performance is dependent on personality. This stems from social facilitation theory, or the way one’s environment stimulates or impairs performance, which influences both cognition and performance. With music, the piece’s complexity, the listener’s boredom-proneness and social stimuli can affect cognition and task performance.

“Social facilitation theory has multiple components to it,” Aiello said. “Attention is one component, and that’s particularly within the cognitive domain, but there’s also the arousal component — the presence of other people has been known to impact how people perform. If you are more aroused, you might have a better opportunity to put some of that toward the task at hand.”

The Iowa City Community School District implemented a district-wide technology policy aimed at reducing students’ use of devices during instructional time. Effective Jan. 21, the policy requires students to remove cell phones and headphones in classrooms. While many students utilize headphones and devices in school, Zhu believes that music has little impact on her learning ability, but rather her mood.

“Music keeps me happy — it doesn’t really help me focus or do better in school,” Zhu said. “[Music also] keeps me not bored all the time. I’ve also learned to zone it out, so I’m paying attention to the teacher.”

Although Crossett believes using music in educational settings can be beneficial for students, she acknowledges that it may be distracting for some.

“If there were someone who was like, ‘I really want to listen to this music right before I take my test to hype myself up for it,’ I’d be like, ‘Absolutely, do what you got to do,’” Crossett said. “The difference is, [when you’re] in the midst of taking a test or engaging in an academic task, music can pull your focus away from that.”

Ultimately, students must utilize metacognitive strategies to remain mindful of what music will distract them the least. Aiello recommends that students analyze their own learning capabilities and environment before listening to music while multitasking.

“It’s one thing to have elevator music on — it’s another to have intense [music]. If you have the least bit of complexity in your task, you feel overloaded or overwhelmed having loud, complex music in the background. It’s the nature of the task, your capability, personality and external stimuli that make a big difference,” Aiello said. “You want to make sure you’ve reduced the number of distractions as much as possible.”

Although music may pose as a distraction in work settings, Dvorak finds that music ultimately strengthens connections in a world where many feel disconnected.

“Music helps connect people together — whether it’s drumming or singing, [music] mediates the release of oxytocin, a neurochemical that allows us to bond and connect with others. By doing music together, we feel closer to people around us,” Dvorak said. “That’s really important, especially when many feel isolated from others. Music brings people of all backgrounds, ages and characteristics together and helps us feel more connected.”

This story was originally published on West Side Story on January 22, 2025.