Disclaimer: The term “woman” is sometimes used in the following article to refer to people who menstruate for the sake of consistency with sources. Not all people who menstruate are women, and not all women menstruate.

It’s 9 a.m. on a Tuesday. A junior sits in her first-period class, clutching her stomach as her body feels like it’s trying to tear itself apart. She woke up this morning in pain, feverish and nauseous, but she’s not technically sick, so she has to go to school — her period is “normal.”

Every month, roughly 1.8 billion people menstruate. In fact, there are about 300 million people on their periods at any given time.

Menstruation is treated differently by different cultures around the world. Women’s Health Magazine published an article in 2016 exploring how people experience menstruation globally, and the stories from women around the world varied widely — from cultural celebrations for girls who get their periods to being kept at home until it’s over.

The culture in the United States typically lies between the two, though the presence and intensity of social stigma vary by situation and place. Periods are talked about, but not often celebrated.

With time, technology has advanced, and the understanding of menstruation has changed. For example, the long list of premenstrual symptoms and period side effects has been further developed — from headaches to nausea to, infamously, menstrual cramps.

The prevalence of pain

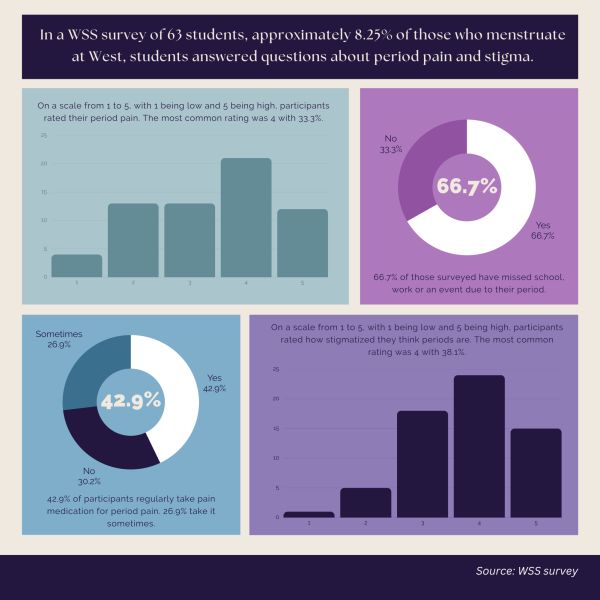

In a 2023 study, 84% of respondents reported having moderate to severe menstrual pain. Severe cramps, known as dysmenorrhea, are common and can interfere with women’s daily lives.

According to West High nurse Jamie Mears, menstrual side effects are the most common reason female students come to the health office.

“One of the number one complaints when [female] students come in is menstrual cycle or period pain, cramps, nausea, vomiting, a lot of those side effects caused by pain in general,” Mears said.

Ruven Andrews ’26 said that before they started medication for their dysmenorrhea, they would be bedridden due to pain and subsequently miss school. Missing one day a month may not seem like much, but by the end of the year, those days would add up to almost a week and a half of school missed due to period pain.

There are multiple ways to cope with the pain, and they largely fall under two categories: medication and lifestyle changes.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as Advil or Tylenol, are often the first line of treatment due to their accessibility, effective pain management and minimal side effects — though, excessive use can lead to nausea, stomach pain, stomach bleeding or ulcers.

When it comes to lifestyle changes, many people find using a heating pad or even exercising helps manage pain. Physiotherapy, abdominal stretching and connective tissue massage are proven to mitigate pain, among other benefits.

However, at school, most students can’t utilize a heating pad or stretches. They aren’t allowed to keep medications like Ibuprofen or Tylenol on them at school, and the nurse’s office doesn’t keep its own stock of those medications, either.

Students are able to store their own medication in the office so they can have access if they need it. Students under the age of 18 can find the necessary paperwork to do so in the nurse’s office.

Some people, such as Andrews, take prescription medication to help manage their menstrual symptoms.

“[My doctor] was able to diagnose me with dysmenorrhea, which is that extremely painful period, [and] heavy flows,” Andrews said. “She was able to get me the right medication, and if any complications came up, she handled it swiftly and effectively.”

But even with multiple coping mechanisms, sometimes period pain gets in the way of daily life. Eva Esch ’25 has a connective tissue disorder, and her pain often gets in the way of things as simple as going to school in the morning.

“When it’s really painful, it’s quite debilitating. I have to take meds, and sometimes I do have to miss school for it, and it’s difficult to do anything really,” Esch said.

Many medical conditions result in worsened period pain, such as endometriosis, where tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside of the uterus, or fibroids, where noncancerous growths form in the uterus.

While conditions that result in worsened period pain are very common — for example, about 77% of women develop fibroids at some point in their lives — women sometimes struggle with getting the right treatment for their pain.

“It can be difficult to have doctors understand, especially with a connective tissue disorder, because there really isn’t that much to be done about it,” Esch said. “I feel like being a young woman also has something to do with it. You could bring up any problem, and they’ll just be like, ‘Oh yeah, that makes sense.’ And you just got to live with it.”

The importance of education

Quality education on menstrual health isn’t always accessible, despite the fact that about half the population will menstruate at some point in their lives.

Last year, fourth-year medical student Pratyusha Bujimalla founded the University of Iowa’s chapter of the Period Education Project, a national physician-led organization that aims to improve access to education regarding menstrual health. The U of I’s chapter is small and made up of around five medical students besides Bujimalla.

To expand access to period education, the U of I’s chapter of the PEP takes matters into their own hands, visiting local high schools and other local programs to help educate young people about menstruation.

“When we talk about period health and how we counsel kids and teens about period health, we want them to have a really good understanding of their own bodies,” Bujimalla said. “And the ability to talk to their loved ones and to their doctors about [periods], and what that looks like, what healthy should be and what to do in case something isn’t how it should be or doesn’t feel healthy to them.”

And while health classes are required in the Iowa City Community School District, sometimes these classes skip over information. The PEP aims to break down their knowledge about menstrual health into what is most helpful for young women.

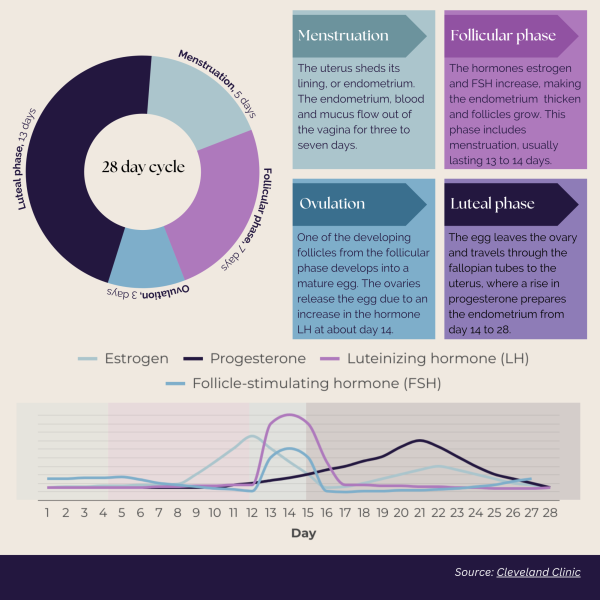

“Sometimes when we think about period health or what health class was like when we were back in middle school, it’s either you completely skip over the things that might be really important and helpful, or you spend a lot of time looking at these charts about hormones that may or may not be really helpful to a kid who’s just trying to understand why all of a sudden they’re bleeding for a couple days out of the month,” Bujimalla said.

In the ICCSD, health education starts in fourth grade with lessons about communication, safety in relationships and puberty. In fifth grade, students learn more about anatomy, sexual harassment and sexually transmitted diseases. With the limited time given for this instruction, that education doesn’t always outline what is healthy and what isn’t.

So, when does one’s period become unhealthy? It depends on the person, but Bujimalla said there are some signs that something may be wrong.

For example, if a person relies on NSAIDs to curb period pain, that medication should be able to manage pain just by taking the recommended amount and for only a few days a month. If that medication isn’t working, it may be time to see a physician.

The line between what is healthy and what isn’t when it comes to menstruation is a big focus of the PEP’s programs.

“Can we talk about when is the pain too much? And when should you be talking to a doctor about these kinds of things? Or finding your mom, your dad or a loved one to talk to you about these kinds of things?” Bujimalla said.

Educating young people about periods helps combat stigma by simultaneously giving them a space to talk about periods and providing them with the tools to advocate for themselves if they are worried their period isn’t healthy.

Breaking the cycle

Period pain is a reality of almost everyone who menstruates.It isn’t necessarily something that can be eliminated completely — but stigmas can.

“I think a good way to [challenge stigmas] is just trying to combat some of that shame that we have within ourselves, and trying to talk more openly about it,” Esch said. “Maybe you don’t put your tampon up your sleeve when you’re walking to the bathroom. Or maybe you can say, “Oh, I’m in a lot of pain today because I started my period,” instead of just trying to hide those little things.”

It’s fair to say that the social stigmas in western culture have come a long way from where they were centuries or even a few years ago, but many people still experience stigmas around talking about their period.

“It’s seen as disgusting for some reason, even though since the dawn of humans, women have had periods, and after all this time, why are we thinking of it as something bad that should be shunned?” Andrews said.

A 2022 study by Mary M. Olson, Nay Alhelou, Purvaja S. Kavattur, Lillian Rountree and Inga T. Winkler examined the effects of the stigma around menstruation. Within the study, the authors write: “These impacts range across all facets of menstruators’ lives, yet they all relate back to power relationships in a society characterized by sexism and misogyny. Menstrual stigma carries an invisible power to define what is normal and acceptable—and what is not. The hairpin is; the tampon is not. A broken bone is; endometriosis is not. Education on nutrition is; menstrual literacy is not. Menstrual stigma is so pervasive and deeply embedded that it remains largely invisible.”

The impacts of not talking about periods are wide-ranging: from shoving a tampon up a sleeve when walking to the bathroom to not talking about being in chronic pain. Mears said that stigmas surrounding menstruation and the idea that period pain is “normal” can make it difficult for women to know when to seek help.

“My big thing with the stigma is we don’t want females to feel like they should not go seek treatment or help because we’re saying it’s normal to just have that pain,” Mears said. “I would say if it’s, if it’s abnormal to you, then you should go get it checked out, because there are things that medically [doctors] can prescribe… [and] there’s other reasons you can have abdominal pain even with your period.”

The reality of how some people experience periods can be very different from what is represented in media, like commercials for period products.

“I think sometimes there’s some stigma associated with pain tolerance and the exaggeration of what periods really look like and how painful they can be. People don’t believe how terrible it is sometimes,” Esch said.

A 2019 study of 32,748 women reported that symptoms of menstruation can cause a loss of productivity that is longer when they go to work on their period, as opposed to staying home. The study also exposed a lack of flexibility in both work and school schedules for women on their period. 13.8% of respondents reported absenteeism during their period, with 3.4% reporting it every or almost every period.

Women also struggle with access to period products.

“Everyone who’s menstruating can relate to those 10 minutes that you’re in the bathroom trying to find a period product, and it’s so lonely. You have so much dread. It is embarrassing. It shouldn’t be, but you’re made to feel like you’re inconveniencing the people around you for not being prepared enough on your period. And that’s something that students should not be feeling from their period,” Maanya Pandey said in an interview with the Des Moines Register.

Pandey, a junior at the University of Iowa, started the non-profit Love for Red with the goal of ending period poverty. Padney is an advocate for Iowa’s House File 883, which, if passed, would require free period products to be provided in school bathrooms.

As of January, 28 states and Washington D.C. have passed legislation to help improve access to period products —— Iowa is not yet on that list. But people like Bujimalla and Padney will keep up their fight to improve access to education and products alike.

Organizations like the PEP and legislation like HF 883 are making big strides to destigmatize periods and support women, but that doesn’t mean that smaller actions aren’t effective. Staying educated and having open conversations about periods is half the battle, and it’s something that everyone can do, whether they menstruate or not.

“We don’t always do a really great job of taking care of women. We don’t always put in the same money and time into research and those kinds of things as we should. And I just thought I really wanted to be a part of the solution to that problem,” Bujimalla said.

This story was originally published on West Side Story on April 24, 2025.