Understanding mental, physical aspects of pacing, distance racing

Sidekick File Photo

Coppell junior Lane Jacobs stays ahead of a pack at the Coppell Invitational on Sept. 4, 2019 at the course at Coppell Middle School West.

November 17, 2020

Whether pushing off the starting block for a 500-yard freestyle or starting a 5K run alongside many others, distinct patterns emerge as long-distance racers compete using various strategies tailored to improve performance.

Coppell’s long-distance racing and training strategies are designed to avoid buildup of lactic acid. Typically, the human body gets its energy aerobically (with oxygen) but when unable to get that energy as quickly as necessary through aerobic respiration during intense activity, the body will switch over to anaerobic respiration. This is the use of lactic acid that builds up in the blood as the strain of activity increases. Eventually, the acid reaches a threshold and at this point, the amount of lactate in the blood is overwhelming and a racer is forced to stop.

From this comes the discovery that going all out at the beginning of a race is less successful than going all out closer to the end.

“It’s very scientific, it’s pure physiology,” Coppell swim coach Marieke Maestebroek said. “[When] I talk about a longer race like a 500 [yards], [a swimmer] has to stay out of that oxygen deprivation zone where they don’t build up that lactic acid early on in the race in their muscles, because they won’t get through the whole 500 yards. Now if you do a shorter race, they’re going to get [lactic acid building] in the start, but if they get too crazy with it in the beginning, they won’t get through the race in a decent way.”

Similarly, Coppell’s strategies for racing the 5K in cross country are derived from personal mile times. In order to avoid reaching a lactic acid threshold too quickly, runners practice with tempo runs to increase the threshold, allowing the body to more effectively clear lactate. In these runs, runners run just below their 10K pace, which is the fastest they can go while aerobically respirating.

“Let’s say you have five miles,” Coppell cross country coach Nick Benton said. “If we were doing a tempo run, it would be about 40 seconds slower than your mile time, which would then get you ready for a race. In your races, you’re trying to go below that 40 seconds.”

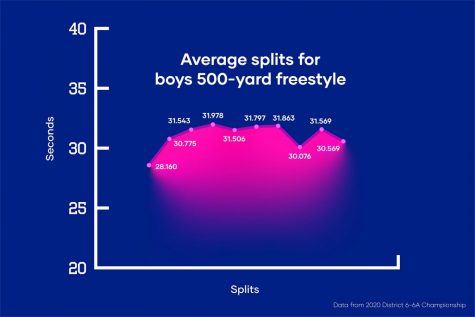

For swimming, the approaches to pacing vary across races. For the longest distances, 500 yards, the first 100 yards are a sprint, the next 200 are at a steady pace, and swimmers pick up speed again during the last 200 yards. The last 100 yards is an “all out swim,” in which runners expend all their remaining energy. For shorter distances, the strategies are relatively similar, though sometimes the pacing differs based on a racer’s muscle fiber.

“There are some exceptions in longer races; some kids are sprinters and they don’t have that pickup speed, so sometimes you have to tell them to sprint the whole thing,” Maestebroek said. “The race strategies aren’t much different [by swimmer], but they can depend on which muscle fiber the kids have – that’s genetic and somewhat it can be trained but limited.”

At other times, pacing for swimming changes depending on stroke and swimmer. Although the only 500-yard race is freestyle, the next longest competition is 200 yards for all other strokes. The planned approaches are the same for this race, but some swimmers are able to sprint the entire distance. The 200-yard individual medley is especially different, as it requires multiple changes in stroke.

“The 200s are pretty similar as for when [it feels like] the man with the hammer hits you,” Maestebroek said. “Breaststroke can be very difficult on the legs. but the medley is more like a long sprint because every time you switch strokes, you use different muscles, almost like it alleviates you.”

According to Maestebroek and Benton, racing is largely mental.

“There’s a few people who are mentally talented that can bite through that difficult part of the race, the part of the race where there’s so much lactic acid buildup,” Maestebroek said. “You can train yourself to get tougher in practice to get through that uncomfortable part of the race better but some people are mentally tougher and able to ignore it and cut through it better than others.”

Beginning any race, the immediate starting speed is typically the fastest a racer will go throughout. Common belief holds that the end of any race is the toughest but in reality, the end of races often turn out to have the second fastest paces. Instead, the third quarter of any race tends to be the hardest and slowest – mainly from a mental standpoint – as racers feel their top speed has already been met.

“That last quarter of the race is just adrenaline keeping you going to finish the race, you can always finish fast when you want to win no matter how tired you are,” Coppell senior cross country runner Colin Proctor said. “When you start the race, you’re nice and fresh, you go out hard ready to run, then at about the midway point you start to feel it a little and it starts to hurt but you push through. That third quarter though always defines who is stronger mentally because that’s where most people give up.”

This story was originally published on Coppell Student Media on November 16, 2020.

![IN THE SPOTLIGHT: Junior Zalie Mann performs “I Love to Cry at Weddings,” an ensemble piece from the fall musical Sweet Charity, to prospective students during the Fine Arts Showcase on Wednesday, Nov. 8. The showcase is a compilation of performances and demonstrations from each fine arts strand offered at McCallum. This show is put on so that prospective students can see if they are interested in joining an academy or major.

Sweet Charity originally ran the weekends of Sept. 28 and Oct. 8, but made a comeback for the Fine Arts Showcase.

“[Being at the front in the spotlight] is my favorite part of the whole dance, so I was super happy to be on stage performing and smiling at the audience,” Mann said.

Mann performed in both the musical theatre performance and dance excerpt “Ethereal,” a contemporary piece choreographed by the new dance director Terrance Carson, in the showcase. With also being a dance ambassador, Mann got to talk about what MAC dance is, her experience and answer any questions the aspiring arts majors and their parents may have.

Caption by Maya Tackett.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/53321803427_47cd17fe70_o-1-1200x800.jpg)

![SPREADING THE JOY: Sophomore Chim Becker poses with sophomores Cozbi Sims and Lou Davidson while manning a table at the Hispanic Heritage treat day during lunch of Sept 28. Becker is a part of the students of color alliance, who put together the activity to raise money for their club.

“It [the stand] was really fun because McCallum has a lot of latino kids,” Becker said. “And I think it was nice that I could share the stuff that I usually just have at home with people who have never tried it before.”

Becker recognizes the importance of celebrating Hispanic heritage at Mac.

“I think its important to celebrate,” Becker said. “Because our culture is awesome and super cool, and everybody should be able to learn about other cultures of the world.”

Caption by JoJo Barnard.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/53221601352_4127a81c41_o-1200x675.jpg)