In 2016, Leah John, a freshman at Dougherty Valley High School (DVHS), experienced her first interaction with the dress code.

While doing quiet work in one of her classes, John’s teacher called her up to their front desk and told her plainly: go to the locker rooms to cover up or to the front office for a dress cut.

“My spaghetti straps were allowed according to the handbook yet my teacher called me out in front of the class and asked me to change,” John said.

Terrified of being disciplined, John left to change into her PE uniform. In tears, John begged the gym teacher to pause his class and open up the locker room for her.

That was just the first of four “humiliations” she endured because of the dress code in her four years at DVHS, where a lack of data, inconsistent enforcement and insufficient communication pathways made it hard to measure whether dress code discipline is implemented fairly.

The discriminatory nature of school dress codes isn’t uncommon. According to former California State University Sacramento student Jaymie Arns’ master thesis on California high school dress codes, 31.9 percent of the dress codes evaluated targeted male students of color and “37.9 percent of the total dress code rules targeted high school girls,” using words such as “immodest” and “revealing” to place “responsibility and blame on the female students to preserve a distraction-free learning environment.”

There is also no shortage of outrageous dress code enforcement in the national headlines either. In a 2014 article published by The Nation, Cecilia D’Anastasio reported that students from high schools in New Jersey, Texas and New York and a middle school in California “have issued complaints about their dress codes, many of which have resulted in full-on protest.” D’Anastasio finds that stories from female students about harassment, dismissal from school or forced dress into gym clothes are “rapidly becoming more prevalent” on platforms such as Tumblr and Twitter.

The San Ramon Valley Unified District (SRVUSD) or DVHS was not referenced in the D’Anastasio article. Nor has the district or school gone viral on major social media platforms for problematic dress code enforcement. That goes for the majority of districts or schools across the country as well; you could understandably call the examples outlined in D’Anastasio’s story “outliers.”

That’s where the common misconception lies: because we haven’t seen explicit condemnation or a groundbreaking protest movement against our dress code, our school — along with other schools across the country — is perceived as a “moderate” school in comparison to the ones that do receive major public backlash. This results in the district’s dress code appearing relatively acceptable and harmless.

The problems behind the dress code aren’t just the ones in the media. The narrow stereotype of an unfair dress code vindicates DVHS when in actuality, we have plenty of problems with our dress code policy— they are just more complex than the issues presented in the media.

Hidden flaws in DVHS’s dress code policy: lack of data collection

One of these problems is the absence of data around discipline.

SRVUSD uses Infinite Campus (IC), a student-parent information portal, to track student records of attendance, grades and discipline. However, per state education guidelines, only the reasoning behind disciplinary actions such as suspensions and expulsions is required to be logged into the system.

For any discipline below suspension, DVHS Assistant Principal Lauren Falkner explained that “defiance” (defined as repeated resistance to authority) is a sufficient explanation in IC. This means that even if a detention is given to a student as a result of multiple dress code violations, IC would not provide that explanation. Thus, the vague nature of how disciplinary action is detailed makes it impossible to determine the true extent to which dress code enforcement influences disproportionate discipline.

Johann Somerville, DVHS United States History and AP Research teacher, doubts that IC is tracking all disciplinary action. Somerville said he thinks the less conventional forms of “punishment” yet more common consequences involving dress code violations– such as requiring a student to change into a different shirt — are not being recorded at all. He urges the administration to collect more definitive data.

Arns’ research finds that most dress code policies list the first offense punishment as changing into alternate clothing, which is why it constitutes 85.7% of punishments related to dress code violations; this was the punishment John received when she was first dress-coded in freshman year.

According to Arns, this consequence disproportionately affects female students because they “cannot take off their dress or shirt and continue to class, so they are removed from class until they can change.” On the other hand, “offending clothing worn by male students can easily be corrected by removal of a hat or pulling up sagging pants.”

The impact is concerning — a certain gender group receives less education than another. When John went down to the locker room the first time she was dress-coded, she missed almost the entire class lesson that day.

Arns explains that “any time instructional time is lost, the academic development of students is hampered, diminishing their probability of success.” Furthermore, a study published by the UCLA Law Review finds, “the amount of instructional time a student receives is an important predictor of achievement.”

As there is no written record of whether a student has to leave the classroom to get changed, not only are they receiving less education but the administration is also unable to find these patterns and take steps towards fixing the problem.

To prevent a repeat of John’s scenario we need to have better data so that we can analyze and prevent it from happening again.

“It’s more than just the student’s record. It’s an ability for us to collect data and analyze it to address issues,” District Director of Student Services Ken Nelson said.

Teacher training surrounding enforcement

The persistence of unjust enforcement based on personal interpretations of the dress code is largely due to a lack of teacher training.

“I printed out the dress code and I highlighted the area that showed that she could not dress code for having spaghetti straps,” John said about her third experience with the dress code.

According to John, as a reaction to her printing out the dress code and presenting it, John’s teacher said: “Sorry, I know it’s not against the official dress code, but this is too much,” while “pointing at [her boobs].”

The infiltration of personal bias in John’s case is clear. It may have been her teacher’s own opinion that her breasts were “too much,” but that judgment is nowhere in the written dress code. But if it bothers the teacher, could that still be grounds for a dress code violation? It’s a question of whether the situation is truly a disruption of the learning environment or “[their] problem, not mine,” John put it.

When asked why the district does not mandate teacher training on accurate dress code enforcement, Nelson explained that it would be “really difficult, especially when things are slightly different” between school policies. Thus, it falls more on individual sites to carry out training with staff.

“It’s probably at the beginning of the year or if dress code starts to become an issue, then they might talk about [it at] another staff meeting,” he said.

Because individual site training is not district-mandated, it depends on the initiative of each school. California High School has a specific clause in their handbook addressing training: “school staff should be trained and able to use student/body-positive language to address code violations.” But DVHS’s handbook has no such clause.

In fact, according to both DVHS Principal Evan Powell and Falkner, there is no official training on dress code enforcement. The only “training” that is conducted is an announcement at the beginning of each year that teachers should call administration if they feel “uncomfortable” disciplining a student for a dress code violation.

This reminder centers around the prioritization of teacher comfort, not students’, which should be the entire purpose of implementing training in the first place.

So, what can be done?

First, sites need to ensure that teachers understand the specific policies of their school’s dress code. Whether that’s by hosting training throughout the year or even implementing some sort of “quiz” for teachers at the start of each year, it has to be done somehow. We cannot tackle the problems in writing while teachers are enforcing different policies in the classroom altogether.

As for change on the district level, according to Nelson, the district has the capability to require training across schools if they want to. Following up to the Courageous Conversation program (focused on anti-bias training and culturally sensitive teaching), the district should invest in similar training initiatives for school sites, but with a specific focus on the skills necessary to carry out fair dress code enforcement, especially with regard to equity.

This includes general anti-bias training, but also teaching staff about body positive language and body shaming.

Teachers and administration should also be exposed to the data that exists on disproportionate dress code enforcement. Educating teachers about the history of dress codes, the statistics surrounding sanctions affecting marginalized students more adversely and other research that acknowledges the ideological issues with dress code policies is a necessity. Making teachers aware of the dress code’s negative potential can help schools rethink punitive enforcement as well as avoid unfair judgement.

Impractical communication pathways

It is always possible that a student feels they are unfairly treated under the dress code, no matter the policy. This brings up the need for communication channels between students and administration to voice concerns and suggestions.

Unfortunately, neither of the three main communication pathways outlined by SRVUSD are sufficient.

The first way a student can communicate their concerns is by going directly to their school principal. In fact, Powell prefers students to default to this option.

“No one needs to go above my head; it’s going to come back to me anyways. We can resolve anything and if I can’t, I’ll be the first one to say ‘let’s kick this up to a director and let them make the decision,’ because that’s how it goes,” Powell said.

However, the assumption that students feel comfortable enough to communicate their concerns face-to-face with administration is not necessarily true.

No matter how welcome the administration paints themselves to be, a student reporting an experience where they felt treated unfairly is inherently daunting.

“It’s hard to speak [up] against authority, because you always assume they’re right,” John said.

Additionally, if a student felt wrongly disciplined by the school administration, it may not seem like an ideal option for a student to ask for help from the very actors that hurt them. It is understandably hard for students to place their trust in those who violated it in the first place.

That’s where the second option comes in.

“If you’re not comfortable talking to your administration about what your concern is, you can always go the ‘Report a Concern’ route,” Nelson said.

Located on the district website homepage, Report a Concern is a form open to all SRVUSD community members that can be used to report any type of federal or state-specified discrimination. District staff are required to respond within 48 hours to anyone who fills out a report.

The biggest issue with this option is that students don’t know it exists.

John said that she never knew about Report a Concern, even though she experienced multiple instances of unfair treatment by school administration regarding dress standards in her freshman year.

DVHS former student Fern Torres was also unaware of Report a Concern, agreeing that the option “is not properly communicated” to students.

“Publicize it more if you care about it,” John said, suggesting that the district make the form readily accessible on individual school websites (in DVHS’ Quick Links section, for example) because students use their own school sites much more frequently than the district page.

The last main option students have is perhaps the most impractical of all: filing a Uniform Complaint Procedure (UCP) complaint.

Similar to Report a Concern, students can fill out UCPs if they feel they have been unfairly discriminated against for their race, gender and a variety of factors listed on the district website.

The difference is that the UCP requires the district to conduct an unbiased investigation (if district-initiated meditation with the complainant and district is not successful) of the concerns, making it much more serious than Report a Concern.

However, the district takes up to 60 days to complete the investigation and notify the complainants of the results — an extremely lengthy process that does not guarantee reassurance to the student who may have filled out the report.

John says this daunting timeline makes it unlikely that students consider this path of communication, even if the gravity of their situation matches UCP criteria.

“I’m not going to spend that much time. I’ll just force myself to get over it,” she added, explaining that she would not choose the UCP option even if she did not feel comfortable bringing her issue to school administration.

Future steps

SRVUSD has a lot to reflect and take action on in light of ongoing societal events, such as the country’s racial reckoning. This period of reflection gives us the chance to change problematic policies, which makes the issues with the dress code more relevant than ever.

“If this is an opportunity for discipline, it is an opportunity for inequity,” Director of Communications and Fundraising for nonprofit Human Solutions Lisa Frack said. “In a time when districts are saying, ‘how can we reduce inequitable punishment,’ why not lift an opportunity for that?”

To start, the district can try piloting the Model Student Dress Code across all schools, which was first implemented in Portland Public Schools in 2016 with the help of Frack. The policies listed in the code are limited, specific and gender-neutral, minimizing grounds for disproportionate enforcement. If it’s been successful in PPS and a handful of other schools for years, then it’s worth a shot.

Arns went a step further to suggest piloting a program that eliminates the dress code altogether. The underlying reasoning under that idea is that students will likely still dress appropriately out of common sense and parental approval.

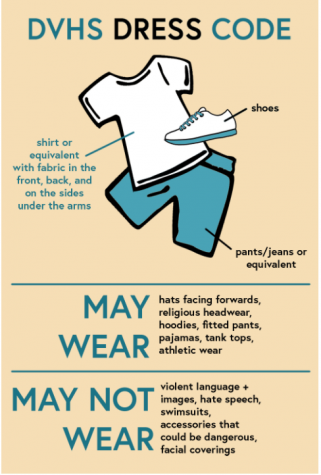

“We don’t need these rules; no one is going to come to school in a swimsuit because it’s just not comfortable,” John agreed.

At the end of the day, John was one student out of thousands at DVHS that has had negative experiences with the dress code.

But she is not alone.

Just because John chose to publicize her experiences does not mean she is the only one with those experiences. It is incredibly difficult to come forward about these situations, and John admitted that it was “humiliating” to endure what she went through. For all we know, there are so many more students that share similar experiences as John in regards to the dress code.

Although John’s story is a singular story, we shouldn’t need more of the same stories to know that this is an issue. It is morally wrong to define the problem solely by numbers when the impact falls on human beings; if we disregard this problem because John is only one example, then we also disregard John as a person with real experiences that deserves to be acknowledged.

Hearing about the problem once is enough to know that change is necessary.

This story was originally published on Wildcat Tribune on August 16, 2021.