The price to play

Extracurriculars can enrich a student’s high school experience through skill development and learning opportunities. But, like anything, they come at a price.

Zoey Guo

From sports to music, extracurricular activities can enrich a student’s high school experience. However, participation often comes with a steep cost.

October 4, 2021

Hard work beats talent when talent doesn’t work hard. But does hard work beat monetary resources? Without proper financial investments, success in sports, music and other extracurriculars becomes far less attainable. With no means of getting to the starting line, winning the race is an impossible task.

Weighing the cost

In high school, most students highly anticipate joining new clubs and sports — some are freshmen already looking to pad their college applications while others simply want to gain new experiences and have fun. Although the amount of opportunities may seem infinite, the resources required to take advantage of them certainly are not. A student at West, who wishes to remain anonymous, has one car for their family. This creates a barrier for transportation and has stopped them from pursuing their interests.

“My dad works five days a week, and … my dad drives [my mom] to [work]. It’s really hard for us to get a time so that our dad can drive us since I don’t have a driver’s license,” the anonymous source said.

The transportation roadblock extends beyond parental unavailability — public transportation or carpools are difficult to coordinate around the anonymous source’s schedule. They believe missing out on extracurricular activities will affect not only their high school experience but also their post-secondary opportunities.

“First of all, you don’t get the experience of leadership or working in a team, which is a huge part of being in high school,” they said. “Second of all, it really detriments the process of college applications … because [extracurriculars are] a really huge part of that, and if you have nothing to put in there … then it’s going to conflict [with] your future and where you’re going to go.”

These disadvantages are reflected on a larger scale. A 2015 study investigating the relationship between income and extracurricular participation found that the participation gap between lower and middle to high-income students is widening. Head Speech and Debate coach John Cooper understands how this disparity is perpetuated in the form of high school students who have to spend time working.

“There are kids who work because they have to,” Cooper said. “They will not have time for debate. I don’t like it, but that’s just … a structure that’s bigger than the building; that’s our society. Some kids just have to work.”

The anonymous source believes the district is not doing enough to address these issues.

“I feel like [the district] is pretty ignorant in their efforts because West High has been here for a pretty long time, and [West] is an excellent school, but they haven’t really assessed this,” the anonymous source said. “It’s kind of gone into a hole where there’s no communication.”

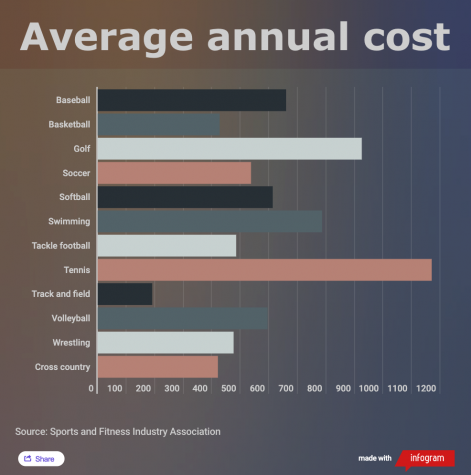

An unfair race

Long touted as the great equalizer, sports have been a quintessential aspect of many Americans’ childhoods. Despite their reputation, youth and high school athletics come at a steep price. Kids from low-income families are six times more likely to quit sports due to costs, according to the Aspen Institute’s Project Play. From Little League to private swimming lessons, almost all organized sports are pay-to-play, and it’s not uncommon for some parents to shell out thousands of dollars to get their children off the bench — but what about families who can’t afford that price?

For most sports, club or outside training can significantly increase the chance of success in high school. Many benefits come with training alongside others in an organized program, according to Michele Conlon, head tennis professional at the Hawkeye Tennis and Recreation Complex. At HTRC, students receive coaching on strokes, strategy, mental and emotional toughness, and accountability. They also gain valuable experience that increases their chance of success at tournaments.

“Students are exposed to a lot of different game styles and personalities that they will need to deal with in a tournament or in a high school match,” Conlon said.

Varsity tennis player Jayden Shin ’23 has trained at the HTRC since he was in the fifth grade.

“I definitely think that taking private lessons and club tennis has made an impact on me as an athlete,” Shin said.

However, this experience comes at a price. Private lessons at the HTRC range from $44 to $60 per hour, depending on instructor and membership status, which can accumulate to over $2,000 per year if taken weekly. These expenses, added to the cost of rackets, other equipment and tournament fees, can take a hefty toll on any bank account.

“A racket costs roughly $200, and high-performance players typically have two,” Conlon said. “Tournaments can get expensive with a $30 to $70 entry fee, hotel, gas [and] food.”

The HTRC has implemented several policies aimed at increasing tennis’ accessibility, including keeping their rates lower than most in the industry, allowing non-members to participate in training and putting together a diversity, equity and inclusion committee.

While some sports often require more equipment and training, others are generally less expensive. According to World Atlas, soccer is the most popular sport globally, which is commonly attributed to its accessibility — just a ball and two goals are enough to play. Ruichar Medina ’22 played on the varsity soccer team last season despite not having any club experience beforehand. However, playing alongside peers who have trained for years came with its difficulties.

“The practices were a little hard. I just had to stand up and keep moving forward to reach the [varsity] team,” Medina said in an interview translated from Spanish. “I felt a little turned off because [other players] had previous experience playing — it was my first year on the team.”

Medina now plays for the Iowa Soccer Club using the money he earns and has gained confidence since joining.

Track and cross country are also sports that require relatively few expenses for athletes. However, equipment such as running shoes and spikes are essential to participation.

“For our sport, thankfully, there is not a lot of equipment needed other than spikes,” said Travis Craig, West High boys track and field head coach. “We do have to provide spikes to five to 10 athletes each year.”

Having a sufficient supply of running shoes is crucial for varsity track and cross country athlete Sara Alaya ‘22.

“Especially in cross country, we go through a lot of running shoes,” Alaya said. “If a person’s family can’t afford to buy them running shoes every six months … or every certain amount of miles, then that’ll affect their running majorly, and they [will] get more injuries.”

In addition to running shoes, transportation from practices and meets is a limiting factor for athletes’ participation. When buses are not provided for meets closer to school, getting athletes to and from these events can pose a challenge.

“Sometimes the school does not provide transportation, and you’re stuck not knowing how you’re going to get to a cross country meet or track meet,” Alaya said. “[Some athletes] rely on their other teammates, but even then, sometimes we don’t even have enough drivers on the team to transport 40-plus people to a track meet across the city.”

For athletes, fueling their bodies with adequate nutrition is also crucial. However, those that can’t afford a stable supply of healthy food must rely on team resources.

“We depend a lot on our parents of more affluent families to provide these snacks and healthy food for meets,” Craig said. “This is critical to optimal performance in our sport.”

To participate in athletics at West, athletes must submit a yearly physical exam by a licensed physician. Although this may be effortless for some, it can be yet another hurdle to overcome for others.

“Getting timely and yearly physicals is a difficult process for many of our athletes,” Craig said. “Our current policy says that anyone without these things needs to wait and come back once they have these done. Some students never come back since this is such a hardship or because they got turned away.”

For some athletes, excelling in a sport can be their golden ticket to the college admissions game. This ticket, however, is not drawn at random. According to ESPN’s The Undefeated, fewer than one in seven Division I athletes come from families where neither parent attended college. This first-generation status is an important indicator of socioeconomic opportunity, with students typically being from low-income households. Because of their financial status, lower-income families have a harder time providing their children with increasingly important resources, including club membership and individual training, to pursue athletics at an elite level.

For tennis, Shin says participating in tournaments outside of school is crucial to get recruited.

“Tournament matches contribute to a Universal Tennis Rating, which is a key factor in recruitment,” Shin said. “High school tennis is sometimes [neglected] or overlooked during the recruitment process.”

This means that players without the resources to enter expensive outside tournaments are disadvantaged in getting recruited and receiving scholarships. In the end, those who have the money and support to excel have a better chance of coming out on top and reaping the benefits of being paid to play in college.

Instrumental resources

In any activity, natural talent can only take someone so far. A combination of talent and hard work is typically seen as the path to success, but a third factor should not go unmentioned: resources. In the musician’s world, receiving musical training is instrumental for success. Missing out on resources, including private lessons and ensemble experience, at a young age inhibits a musician’s ability to perform at a high level.

In terms of a student’s high school musical career, there are a few standard indicators of skill that would allow musicians to pursue their passion in college. One of these indicators is whether a student made All-State, a statewide festival for band, orchestra and choir that involves a rigorous audition process.

“Playing in a professional orchestra, you need to be on that All-State track,” said orchestra director Jon Welch.

According to a survey filled out by 22 West High All-State musicians, 90% of them take private lessons. Bivan Shrestha ‘22, a two-year All-State flutist, believes taking lessons gives him advantages regarding motivation and accountability.

“[Private lessons] hold me accountable to practice and actually do my work,” Shrestha said. “Having a steady and consistent practice schedule is really helpful for me.”

Not only this, one-on-one time with an experienced teacher puts students on the path to success in terms of skill and technique. From finding appropriate repertoire to pointing out errors in execution, the benefits of having a private teacher are unquestionable.

“It’s difficult to start practicing or have a sense of direction when you’re not really knowledgeable on how things are played,” Shrestha said. “There are going to be a lot of resources online to help you out with that, but it’s not really as individualized as having one person look over your mistakes.”

At West, music directors do their best to provide lessons and additional resources for those in need. Welch recognizes how socioeconomic factors play into the accessibility of music and works to give all students the opportunity to participate in the music program.

“Students that come from a privileged rank are going to have more access to these things,” Welch said. “It’s my job to [work with] the administration, the school board and our community to provide opportunities to students that do not have access to those sorts of things.”

As part of his contract with the school, Welch organizes individual and small-group instruction to those who don’t take lessons elsewhere, such as Claudé Pineda ’22, who has taken outside lessons before but currently does not.

“I think Mr. Welch and the school district are doing their best to accommodate people who don’t have private lessons,” Pineda said.

However, because of the limited resources and time dedicated to music instruction, school-sponsored lessons often don’t provide the most efficient pathway to improvement.

“I’m only able to provide about 20-minute lessons, maybe 30,” Welch said. “Students that are taking private instruction … pay for either half an hour or an hour.”

Aside from specialized instruction, inaccessibility to instruments themselves can cause disparities within the music program. Depending on the quality, both band and orchestra instruments can cost thousands of dollars. To cover this cost, Welch works with local businesses to provide students with the necessary equipment.

“There’s really not a repair or an instrument that we have not been able to get to a kid,” Welch said.

Students on the free and reduced lunch program qualify for price accommodations for school-provided instruments. Welch estimates that about 10% of orchestra members are eligible for this.

Despite resources available from the school, more are often required to reach one’s full potential.

“It’s frustrating knowing that I [could] be an excellent violin player and a great member in the orchestra if I had more money,” Pineda said. “Money always seems to be the main barrier for most things.”

Paying it forward

In an effort to minimize disparities for students who want to participate in extracurriculars, individuals and organizations have proposed several initiatives. According to West High Principal Mitch Gross, the district has been discussing measures to tackle barriers to extracurricular participation, primarily in transportation.

“There has been a push to have activity buses that will provide transportation for students … to take kids to and from [sports] practices,” Gross said.

However, with the cost to provide busing in addition to staffing shortages, it is not known when the ICCSD will implement a solution like this.

To the anonymous source, the school should continue to work toward fulfilling limited resources for all students.

“There should be more of those [resources] set in place that can help people who are eager to do this but do not have the resources,” the anonymous source said.

Student Family Advocate Annie Gudenkauf works to create additional solutions for students without transportation to address this ongoing issue.

“What we typically do with students that have issues with transportation … is to coordinate creative ways to get around, whether that be them purchasing a bus pass, identifying someone they can get a ride with or walking,” Gudenkauf said. “It is a very inequitable situation that disproportionately affects low-income students.”

For athletics specifically, Craig believes that a coach’s role is to bridge the gap between socioeconomic status and participation in sports.

“I think there are a lot of ways all sports are negatively impacted by financial disparities,” Craig said. “I think part of our job is to close that gap as much as possible.”

As part of an initiative to achieve this objective, Craig is currently working on implementing the Harvest City Fly the W scholarship for four-year track athletes on the West boys track team.

“The scholarship was set up to be able to help a four-year member of our team get some money to make college accessible for them. It honors their commitment to our team for four years but also is a reward for spending their time and energy with us,” Craig said. “Since our team is full of people from multiple backgrounds, we want to help all people achieve their goals and dream big. Our scholarship of $1,000 will help in that regard.”

However, the scholarship is currently in need of further funding to launch.

“We are currently only at $6,000 of the required [amount] by the ICCSD to make it a legitimate scholarship. We need and will take any and all support in this regard,” Craig said.

Craig also proposes additional opportunities for low-income athletes.

“Having a day at the beginning of each trimester available [for athletes] to get their physical and making the ‘permission to practice’ form a simple checkbox when they register would be easier,” Craig said. “Any kind of free sessions where potential athletes can get to know the coaches and what each sport is about — this could include free camps.”

To address the lack of resources for athletes, Alaya believes West should increase its supply of available sports equipment for those who need it.

“We need to see West High providing more equipment to everyone,” Alaya said. “For running, we’re expected to buy our own running shoes, track spikes and watches. The only thing we really receive is a uniform, and I think they could do a better job, especially for low-income families, to provide that equipment.”

One of the goals that Welch has worked on as the district performance music coordinator is recruiting more musicians of diverse backgrounds and creating additional opportunities for everyone.

“We have a committee of people looking into finding different performance music opportunities and general music opportunities that we can offer at the high school level,” Welch said. “We’re working with them, translators and various resources at different levels [and] getting our recruitment resources out to all the members of our community.”

Although it is part of her job as an SFA to advocate to the administration, Gudenkauf also believes in the power that families hold to fight for change.

“I am a big fan of community members sharing their stories of barriers to school and demanding better,” Gudenkauf said. “This has historically been what gets those in power to listen and change things.”

This story was originally published on West Side Story on October 1, 2021.