Boys’ High School establishes foundation of excellence for Midtown

1947 Boys’ High Yearbook

In February 1947, the second-to-last graduating class of Boys’ High took a picture. That summer, the last class would graduate from Boys’ High.

November 30, 2021

Seventy-five years ago, in 1946, Boys’ High School welcomed its last class. The next spring, in 1947, both Boys’ High and its sister school, Tech High School, both all-white male-only schools, would shut their doors. In the fall of 1947, the building would be occupied by co-ed Henry W. Grady High School.

In the last edition of the Alciphronian, the Boys’ High yearbook, Principal E. L. Floyd wrote, “For 75 years, Boys’ High School stood for the best in scholarship and character development. Into the finest colleges of the nation and into all walks of life, it has sent an abundance of boys in the life of the South and of the entire nation.”

Boys’ High School was founded 149 years ago, in 1872. Along with Girls’ High School, it was one of the first two schools in the Atlanta Public Schools system.

“You attended a private school if you were wealthy,” Grady alumnus and creator of the Atlanta Public Schools Forgotten Schools blog Shakia Guest-Holloway said. “If you were a poor person, you would either have to depend upon the philanthropic donations of the local city’s wealthy elites [or] board of education. But, elected officials in [Atlanta] felt that it was high time for the city to offer public education to local students.”

Boys’ High was originally located in the basement of Girls’ High but soon moved to a new location in downtown Atlanta. However, this building still faced many issues.

“The original buildings for the schools were basically cracker boxes,” said Cathy Loving, the archivist and historian curator for Atlanta Public Schools from 1985 to 2006. “They weren’t really school buildings. You can imagine what construction was like just after the war because Atlanta was basically burned down to the ground.”

In 1924, due to overcrowding and a fire in the old building, Boys’ High moved to what is currently the Midtown High School campus, which was the school’s final location. The building was originally meant for Tech High, which had begun as the technical department of Boys’ High before turning into a separate school. However, due to the issues with the previous Boys’ High building and the expense of maintaining two facilities, both schools were moved into the new building.

“Tech High occupied the other part of the building we were in on 10th and 11th streets,” Larry Hailey, a former Boys’ High student and former president of the Atlanta Boys’ High School Alumni Association, said. “Our schools had a bitter rivalry in everything, including sports, in which they also had excellent teams. We didn’t like each other very much. The Tech High guys always thought that it was their building, and they were resentful of us being there and them having to share the building with the guys from Boys High.”

After Tech High split off, Boys’ High continued to focus on programs that prepared its students for college, including business and clerical courses. Many Boys’ High alumni went on to be CEOs and other local “power players,” Midtown art teacher John Brandhorst said.

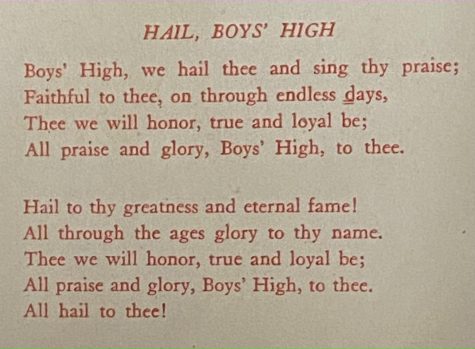

Hail, Boys’ High

Dr. Joe Arnold, a student of Boys’ High until the winter of 1946, fondly remembers his time at the school.

“It was wonderful, everything about it,” Dr. Arnold said. “My time there was a blast, and it was the best place to be and to learn. There were kids there from all over the Atlanta metro area, and it was a melting pot for all different people. The atmosphere was amazing, and getting the chance to go there is one of the best things that happened to me.”

One of the main features of Boys’ High school was its academic programs, which were often considered the best in Atlanta.

“My educational experience was excellent at the school,” Dr. Arnold said. “What was offered to us was like college, and many of us, including myself, were straight-A students, and we ate that stuff up. In the state of Georgia, the education at Boys’ High was second to none, and at that time we were sending more students to higher education than anyone else.”

An important reason for the quality of education at Boys’ High was the faculty, some of whom had attended Ivy League Universities.

“They were really what made the school what it was,” Hailey said. “They were supportive and engaging, and were instrumental in what I was able to do later, just outstanding men.”

In addition to academics, Hailey remembers the fun he had during his time at Boys’ High.

“We didn’t have any way to heat the buildings, except with a little pot-bellied stove,” Hailey said. “I’ve been on the rifle team and knew that, obviously, if you put bullets in a hot stove, they explode. It didn’t hurt anybody, but it went, pow, pow, and scared people to death.”

In 1947, APS transitioned to geographic zones. Boys’ High and Tech High were combined to create Henry W. Grady High School, which served a smaller zone, rather than the whole city.

“I was very upset that Boys’ High ended, and still am,” Hailey said. “I wanted to go ahead and continue because I wanted to be a graduate of Atlanta Boys’ High School. I didn’t want to go to Bass High School for my senior year.”

Although he had to leave, Dr. Arnold said he still carries important lessons from his time at Boys’ High.

“The school turned us from boys into men, and they taught us how to succeed in the real world after college,” Dr. Arnold said. “I still carry the life lessons I learned at the school with me today.”

Boys’ High’s primary goal was preparing students for college. According to an article in the Saporta Report by Boys’ High alumnus Leon Eplan, over 90 percent of the students in Boys’ High classes pursued higher education after high school.

“The college prep at the school was very good, and many of the courses taught at Boys’ High were the same courses taught at colleges, including Biology, Chemistry, Physics and Calculus,” Hailey said. “If you graduated from Boys’ High and applied yourself, you could basically sail through the first year or two of college.”

However, the benefits of Boys High weren’t accessible to everyone. Boys’ High was an all-white, single-gender school, meaning female and African-American students were both excluded.

“I think there was a perception that white men were the ones who were going to carry the torch, and everybody else would follow them,” Brandhorst said. “I don’t think that it’s the way that it should be; there shouldn’t be any white male-only institutions.”

At that time, schools for African-American students were often considered subpar.

“African-American students were forced to attend schools that were just ridiculous,” Guest-Holloway said. “Some students studied maybe with their local church, or they may have received studies from local black colleges.”

In 1947, APS shifted to a co-educational model. The school was renamed Henry W. Grady High School and began enrolling female students. It took until 1961 for the school to become integrated.

“[The 1947 transition] was just part of the push of Atlanta becoming a real city,” Brandhorst said. “It was a time to be modern at that point and modern meant co-ed.”

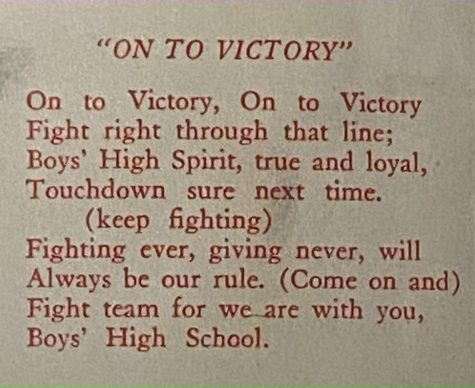

On To Victory

Although its primary goal was preparing its students for college, Boys’ High was also known for its athletics. Larry Hailey was a member of the Boys’ High baseball and bowling teams.

“Playing sports at Boys’ High was a great experience because I, of course, loved the sports,” Hailed said. “The whole school also gave a lot of support,” Hailey said. “I learned a lot by playing sports at the school about leadership, teamwork and being a team player.”

Although Boys’ High had many successful teams, it was most notable for its football team. Led by coach R.L. “Shorty” Doyal, the Boys’ Purple Hurricanes won nine state championships between 1932 and 1946. The high school sports website Max Preps ranked Boys’ High/Tech High as the sixth-best defunct dynasty in high school sports, in large part due to the football teams.

“Shorty Doyal believed in symbolism,” said Todd Holcomb, a historian and co-founder of the Georgia High School Football Historians Association. “He kind of played up the purple colors for royalty and that’s how the players in the team sort of thought of themselves as being something special, and opponents would look at them the same way.”

Doyal’s success at Boys’ High helped him establish a reputation as one of the best football coaches in Georgia.

“[Doyal] didn’t have a rival as a coach and he was considered the greatest coach up until the 1960s or so,” Holcomb said “For the first 50 years of high school football in Georgia, he would be the most well-known coach.”

Jack Cotter played quarterback under Doyal at Marist, where Doyal moved after Boys’ High closed.

“[Doyal] was very demanding,” Cotter said. “If you didn’t pay attention [or] you made a mistake, his favorite attention-getter was ‘we’ll run laps after’ or ‘we’ll do wind sprints.’ He was a very good coach, very smart.”

The football successes of Boys’ High were also due to the talent of the players. Cotter remembers playing with some Boys’ High transfers who followed Doyal to Marist.

“They were really good guys, very talented athletically, and big guys,” Cotter said. “Some went to Georgia, some went to Georgia Tech as scholarship athletes. Chuck Reynolds, who I admired, played halfback for Doyal, and he was very speedy, very fast. He went to Boys’ High with [Doyal]… these guys came over [to Marist].”

Before Doyal transferred to Marist, many of the talented players came to Boys’ High because of his success.

One player who emerged from Boys’ High was Clint Castleberry, who finished third in the Heisman Trophy voting in 1942 as a freshman. Castleberry was killed in World War II after his freshman season.

“Clint Castleberry was probably the best high school football player of his time and he may be one of the four or five best that has ever played,” Holcomb said. “He went straight from high school to Georgia Tech where he almost won the Heisman Trophy as a freshman. …He was a giant, the best anyone had ever seen.”

As a result of their success, the Purple Hurricanes often traveled around the South to play other powerhouse programs. However, their biggest rival was their building-mate, Tech High. The Tech High Smithies won five state championships between 1924 and 1947. Each year, the Purple Hurricanes and the Smithies played against each other in a rivalry game, attracting crowds from all around Atlanta.

“Everyone participated and came to the football games, especially the rivalry game between Boys’ High and Tech High, which was like Georgia and Florida,” Dr. Arnold said. “The atmosphere at the Boys’ and Tech High rivalry game was jovial, especially if we won, which we would more often than not. Thousands of kids came, and there were always some fights orchestrated between the schools. It was very raucous and wild at times, but just a great place to be.”

Although the Purple Hurricanes were successful, segregation prevented the school from playing African-American high schools, likely helping them win more games and state championships.

“This was during segregation; so, you know Boys High [and] Tech High [were] all white,” Holcomb said. “All the players were white; all the students were white. Atlanta had an African-American High School, which still exists, Booker T. Washington, and they had really good teams, as well, but there weren’t as many opportunities for black players and teams, and they didn’t get the recognition … When you start talking about greatest teams, nationally, it’s almost like black high schools are ignored, which is a shame and a tragedy.”

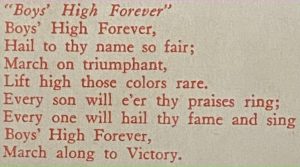

Boys’ High Forever

Although Boys’ High School closed in 1947, its legacy continues at Midtown.

“They established the momentum here,” Brandhorst said. “The best thing that I’ve seen in my 20-plus years here is there’s a momentum to [the school’s reputation], which I think the strength of Boys’ legacy perpetuates. We know the school goes way, way back, and it’s not a school that’s just a few years old.”

Principal Dr. Betsy Bockman believes the Charles Allen building is an integral part of Atlanta history.

“It means a lot to me to be in this building, as it’s a part of Atlanta history and the history of this school,” Bockman said. “There are some issues with being in a building that is one hundred years old, but it is truly a special place, and I don’t think I would rather be anywhere else.”

Alumni from Boys’ High have also contributed to the school over the years. One such example is the arch at Midtown’s entrance, which was a gift from the Boys’ High alumni association.

“They funded the big arch over 10th street which now says Midtown High, not Grady High,” Brandhorst said. “That’s a really important part of our history and it has become a symbol for our school around the state and country overall.”

Boys’ High’s legacy also continues through the Boys’ High School Foundation, which was established by the Atlanta Boys’ High School Alumni association and provides money for Midtown. The foundation provides $10,000 each for Midtown’s Reading, Writing and Math centers. The money also provides a yearly need-based scholarship through the Community Foundation for Greater Atlanta (CFGA) for Midtown students who demonstrate leadership.

“They created this foundation that gives out two scholarships a year to Midtown students,” Bockman said. “It’s $5,000 for four years, for two students each year.”

In addition to providing financial support, the scholarship also provides recognition for students.

“It’s … an affirmation of following a moral character and being a good student, not just academically but in the community,” Ryan Rodriguez, a grants manager at GFGA said.

However, the money from the Boys’ High School Foundation will run out soon.

It is due to sunset pretty soon in 2028,” Rachel Spears the chair of the board of the Midtown High Foundation, said. “There may be some additional funds, so it’ll last a little bit longer, but this is not forever. Sadly, it will come to an end at some point.”

The Boys’ High Scholarship has also inspired others to support Midtown students.

“I just talked to a donor this week who had heard about the Boys High scholarship really loved the idea of it,” Erin Boorn, the Senior Philanthropic Officer at CFGA said. “So he’s thinking about setting up a scholarship fund.”

Even though the money from Boys’ High alumni will run out, the legacy of Boys’ High will continue.

Principal E.L. Floyd ended his message in the 1947 Alciphronian, “The spirit of this school will be felt in the future life of the city … certainly in the lives of all boys and men who have been a part of the student body.”

Dr. Bockman shares a similar sentiment.

“I don’t think we’ll ever forget Boys’ High,” Dr. Bockman said. “It’s just a part of Atlanta, it’s part of the fabric.”

This story was originally published on The Southerner on November 27, 2021.