Victoria Kheyfets holds up a poster in the colors of the Ukrainian flag at the Peace Crossroads in San Jose on March 6 in a demonstration advocating for a ceasefire in Ukraine after Russia invaded the country on Feb. 24. Kheyfets’ family lives in Kharkiv, the second-largest city in Ukraine.

‘I couldn’t believe that I made it’

Ukrainian refugee reflects on escaping war zone as Russian invasion of Ukraine provokes humanitarian and global catastrophe

This is a developing story. Check harkeraquila.com for continuous updates on the development of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

CHAPTER 1: FALLING BOMBS

On Feb. 25, 5 a.m., Harker students were barely awake. Some still slumbered in their beds. For high schoolers in the Bay Area, the day had just begun. For high schoolers in the Bay Area, they were safe.

Yet, halfway across the world, Kristina Petrova (11), a 17-year-old girl who lived with one foot in the U.S. and one in Ukraine, her home country, had just crossed the western Ukrainian border on foot into Slovakia after an around 480-mile long escape from Kyiv. The next 33 hours were a nightmare that yanked her from a day as ordinary as ours — homework, after school practice, evenings with friends — to one of war, chaos and upheaval, in which escape and survival became her sole goal.

“I was in Ukraine, in my apartment in central Kyiv when the Russians invaded Kyiv,” Kristina said. “At 5 a.m., something woke me up — I heard shattering. Then, 20 minutes later, my dad called me from America, and he was panicking. He was like, ‘Kristina, this is not a joke.’”

Kristina lives with a dual identity. After moving from Ukraine to the U.S. when she was 8 years old, Kristina, who currently holds a U.S. green card, attended Los Gatos High School from 2018 to 2021 while simultaneously traveling as an international fencer representing Ukraine.

This past fall, when the 2021 to 2022 school year began, Kristina continued online school, living abroad in Ukraine with her grandmother while attending European competitions.

On the evening of Feb. 23, the Ukrainian women’s national fencing team planned to leave Kyiv for the European Championships in Serbia, a country around 27 hours away by train. Kristina had everything carefully packed — bags, foils, fencing shoes.

Instead, Kristina woke up to falling bombs, smoke and ash, and rather than meeting her coach and teammates, she frantically prepared to leave the country, heading to the nearest train station all alone.

Just a few, short hours later, Kristina became one of tens of millions of Ukrainians watching minute-by-minute in shock as the first Russian missiles targeted the Ukrainian capital. Her first instinct: leave the country.

“At 7 a.m. I took my grandma and we went to the train station,” Kristina said. “It was crazy. People were pushing and shoving, and some people who worked at the train station [Kyiv Passazhirskiy] — they just left. I got the second to last ticket to Slovakia.

At 9 a.m., Kristina bought her ticket. For the next nine hours, she returned to her apartment anxiously awaiting the arrival of her train. At 6 p.m., she returned to the train station, boarded and left for Mukachevo at 8 p.m.

In the hours leading up to her departure, she played one memory from that morning through her mind — pleading with her grandmother to leave the country with her.

“I tried to convince my grandma to come with me, but she said, ‘Even if I make it to Europe, or even if I make it to the west of Ukraine, I’ll have nowhere to go,’” Kristina said. “She gave me 330 euros (362.88 USD). I packed my phone, my passport, my books and folders for school, and I took very little clothes: one sweatshirt, one pair of pants, two shirts, two pairs of socks.”

Even if Kristina’s 76-year-old grandmother left Ukraine, the future could prove even more unstable than her current situation in Kyiv. Unlike Kristina and her family, who all hold green cards, Kristina’s grandmother was rejected each time she applied for an American visa. In these last parting moments, Kristina made her grandmother promise her that she would move to the bomb shelter, converted from the lowest level of their local high school, where hundreds of people in their neighborhood had already begun to shelter. As of March 17, three weeks later, Kristina’s grandmother, along with Kristina’s younger cousin, have also safely left the country and are currently seeking refuge in Germany.

According to Kristina, the trains went much slower than usual. Ukrainian refugees have flooded train stations in many of the nation’s major metropolitan areas, creating the fastest refugee exodus of this century, with more than 2% of the population forced out in less than a week.

“The trains [went] really slowly to avoid accidents,” Kristina said. “Normally, the trip should have taken eight or nine hours, but it ended up taking 13 hours. After 13 hours, I get to this town [Mukachevo], which is in ruins.”

Russian troops invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24 and have bombed multiple Ukrainian cities. The invasion came after months of a buildup of Russian troops on the Ukrainian border and warnings from the U.S. intelligence community of a potential Russian invasion. Thousands of Ukrainians began to flood out of the country, just hours after the invasion.

CHAPTER 2: CROSSING A BORDER

After arriving in Mukachevo, Kristina’s fencing teammate’s father picked her up by car to send her to the border, arriving on short notice after hearing from his daughter that Kristina planned to leave the country.

“The road that crosses Slovakia, there was a big traffic jam,” Kristina said, recalling the moments before she crossed the border. “Ukrainian soldiers were blocking the entrance because Ukrainian men can’t leave the country. It was basically impossible to leave the car. The line was just huge.”

“[The Ukrainian soldiers] raised the pole so the cars could go,” Kristina said. “[For those crossing the border on foot], women had to literally crawl under the poles with their children. It was dehumanizing.”

A couple of hours later, after passing through customs, Kristina was finally — though temporarily — safe.

“I couldn’t even believe that I made it,” Kristina said. “The day before, my parents had no hope that I was going to make it out. When I saw that almost all the tickets were sold out and none of the trains were leaving, I was losing hope.”

Two weeks later, after continuing and finishing her European championships competition, Kristina returned to the U.S. on March 6. Looking back, everything felt “surreal,” according to Kristina.

Russian President Vladimir Putin described the invasion as a “special military operation” allegedly to “denazify” the country. As of Mar. 15, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), there have been a recorded 1,834 Ukrainian civilian casualties, with 691 killed and 1,143 injured, though these numbers are likely low estimates.

“The Putin regime has actually been very effective in the last 20 years or so at disseminating disinformation, and it’s one of its main tools in bolstering its security goals is making sure that everybody is confused and misinformed about what’s taking place,” said upper school English teacher Christopher Hurshman, who held a class discussion on the invasion in his Russian Literature elective.

CHAPTER 3: AN UNCLE CALLS

Anja Ree (11), whose grandmother and uncle live in Ukraine, received a call from her uncle on Feb. 24, the evening of the invasion. Her uncle resides in Odessa, a suburb around 295 miles from Kyiv in the south of Ukraine, and was at the Odessa International airport when the invasion first shook the city.

“If Putin does succeed in completely taking over Ukraine, he has made clear that has this goal to destroy Ukrainian national identity,” said Anja, whose mother is Ukrainian. “For NATO countries to take in refugees would be really helpful. I understand that there’s a limited capacity for refugees, but at the same time, now that Russia is doing this, we don’t really have a choice.”

The UN estimates that around 3 million refugees and around 2 million internally displaced individuals have been created by the invasion. Poland, Romania, and Moldova are the countries that have taken in the most Ukrainian refugees, with Poland taking in 1,916.445 refugees, Romania taking in 491,409 refugees, and Moldova taking in 350,886 refugees as of Mar. 17.

“All the airports were crowded, and now we have all of these refugees from Ukraine who are currently seeking assistance in these neighboring countries,” Anja said. “This isn’t the first time I’ve seen an invasion on the news, but just having this personal connection to it — it definitely feels very different. That’s my country, that’s where I’m from, and they’re destroying it.”

CHAPTER 4: APPLYING PRESSURE TO PUTIN

The U.S, U.K, Canada, EU, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have imposed sanctions on the Russian economy and have removed several Russian banks from the SWIFT financial system, contributing to the fall of the ruble’s worth to less than one cent.

“In terms of the sanctions, I would probably say that what Biden is doing at the current moment is probably not enough,” Anja said. “Russia does rely a lot on the western economy, and so I can see where those sanctions will be coming from, but as of right now, I think what they really need is more direct aid. The country is already running out of arms.”

The U.S. has also banned imports of Russian oil and gas, Russia’s chief export. Both the U.S. and EU have also provided Ukraine’s armed forces with military aid like javelin and stinger missiles as well as fuel for vehicles. U.S. president Joe Biden signed the Bipartisan Government Funding Bill into law on March 15, which provided $13.6 billion in aid to Ukraine. On March 16, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an order that is binding under international law that demands the invasion to be immediately stopped.

“The Ukrainians are better trained now than they were eight years ago … when the Putin regime claimed and annexed Crimea,” Hurshman said. “In fact, the Ukrainian armed forces have been receiving a lot of training and support from some of their Western allies, which means that they may have a chance of lengthening this conflict for Russian forces.”

CHAPTER 5: A CALL FOR HELP

Russian troops targeted a maternity hospital in Mariupol on March 9 and led to the deaths of dozens of pregnant women and children with several others wounded. The bombing prompted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to urge the U.N. to close the skies.

Zelenskyy gained international attention for his leadership during the invasion and has called for Western leaders to form a stronger and more unified response to Russia’s invasion. Zelenskyy reportedly responded to an offer by the U.S. to help him flee Ukraine by saying “I need ammunition, not a ride,” he has also implored NATO to enforce a no-fly-zone over Ukraine, which has been rebuffed by NATO over fears of a possible escalation into armed conflict with Russia.

“What really impressed me is the fact that President Biden suggested to President Zelenskyy of Ukraine to airlift him and harbor him inside the White House, and [Zelenskyy] said, ‘No,’ and the next morning, we got a video of him on the streets of Kyiv, fighting with his native people, which was really touching to see,” Anja said. “That was a very strong moment where I really felt proud of my country.”

CHAPTER 6: WHY IS THIS HAPPENING?

Russia and Ukraine have a long history of tense relations, with both nations claiming heritage from the medieval kingdom of Kievan Rus. The Russian Empire absorbed Ukraine during the mid-17th century, during which the Russian government enforced policies to ensure the “Russification” of Ukraine by forcing Ukrainians to learn and speak Russian and not Ukrainian, as well as suppressing Ukrainian literature and art.

The Soviet Union was established in 1922, after the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 and the subsequent Russian Civil War, with Ukraine as a founding member. Under the Soviet Union, Russification policies softened under Vladimir Lenin but became more strict under Joseph Stalin’s reign.

“Lenin was very okay with independent republics within the USSR because his vision for communism was global,” said upper school history and social science teacher Matthew McCorkle. “Stalin’s perception of things was much more Russia-centric, much more nationalist in that the Russian identity was going to be part of the USSR’s identity. Some of those aspects, I think, then carried over after Lenin’s death.”

Stalin’s policies led to the execution and transfer of several prominent Ukrainian academics and educators to forced labor camps. Russification policies softened under Nikita Khrushchev in the 1960s but became once again stricter under Leonid Brezhnev in the 1970s. In 1986 the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant near the city of Pripyat had a core meltdown, leading to the surrounding area becoming irradiated for the next 20,000 years. The Chernobyl disaster is considered the worst disaster in the history of nuclear power generation. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine became an independent state and gave up its Soviet-era nuclear arsenal in exchange for security guarantees from Russia that they would not attack Ukraine after signing the 1994 Budapest Memorandum.

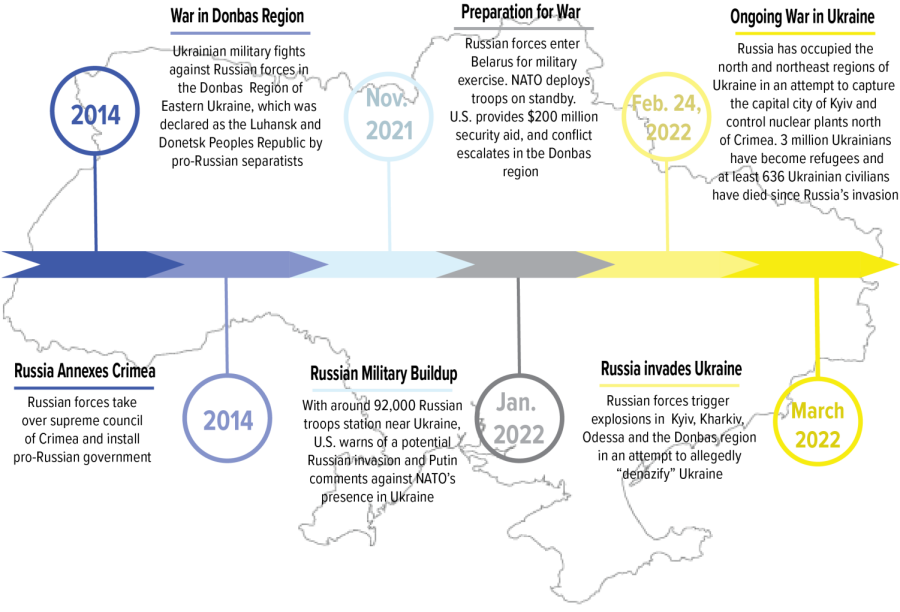

Russia then annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014, violating the Memorandum and beginning the conflict in the Donbas between pro-Russian forces and Ukrainian forces. The annexation of Crimea provoked widespread international condemnation and led to the West imposing sanctions on Russia. Ukraine received more military aid from the West after the annexation of Crimea, and Russia continued military action in the Donbas.

The lead-up to the invasion of Ukraine began last November, with the U.S. and Ukraine observing unexpected movement of Russian troops near the Ukrainian border, consisting of 92,000 Russian troops stationed near Ukraine by Nov. 28, 2021. Russian forces increased their presence by entering Russian ally Belarus northwest of Ukraine on Jan. 17 while the U.S. provided $200 million worth of security aid, including anti-tank missiles and anti-aircraft missiles to Ukraine.

“If [Russia] attempts to occupy central and western Ukraine, it will be just as successful as the American occupation of Vietnam or Afghanistan or Iraq, where if you have a substantial minority of the population that does not want you there, they can consistently make your life difficult enough to make it overly costly to contend with them,” McCorkle said. “It makes it unviable to continue expending resources, attempting to hold that territory.”

By Jan. 24, NATO deployed troops on standby, and the conflict escalated on Feb. 17, with increased Russian shelling in the separatist Donbas regions Donetsk and Luhansk in eastern Ukraine. Russia continued by recognizing the Donetsk and Luhansk breakaway republics on Feb. 21, damaging to Ukraine’s sovereignty as Donetsk and Luhansk have Russian-friendly governments, and Ukraine considers the region part of their country.

Russia then began the full invasion on Feb. 24.

“This is the first interstate war in 75 years,” said Erik Gartzke, University of California, San Diego Professor of Political Science and Director of the Center for Peace and Security Studies. “It’s been such a long time that many in Europe started to think there wouldn’t be any more interstate wars, so one of the things I think you can genuinely see from a lot of people in Europe, and especially in Ukraine right now, is just shock.”

CHAPTER 7: HOW TO HELP

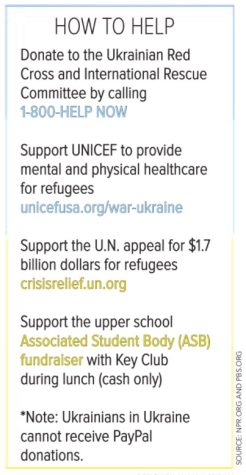

The upper school has launched multiple fundraiser initiatives under the Associated Student Body (ASB) and various clubs including Key Club, Tri-M Music Honor Society, Art Club, Medical Club and Research Club, Aerospace Club, Quiz Bowl and Multicultural Club in order to provide aid to Ukraine. Students have also expressed ways to support their peers in the midst of the conflict.

“Be sympathetic and understand that [people] might not be in the correct mental frame of mind to handle other difficult decisions as we do almost every day at Harker,” Anja Ree said.

Upper school English teacher Christopher Hurshman held a class discussion in his Russian Literature elective on Feb. 25, the day after Russia’s invasion, to provide a “safe space” for discussion and education.

“For me, it’s been really important to just follow the lead of my students and let them decide how much they want to talk about it and not forcing anything,” Hurshman said. “It must be tremendously stressful. I would encourage people to be aware of themselves and engage with these realities of what the world is like, but it’s okay to distract yourself with something else.”

This story was originally published on Harker Aquila on March 23, 2022.