A level playing field: local organization empowers women in sports leadership

Graphic by Sophia Bella

The Women’s Coaching Alliance’s (WCA) central mission is to grow the presence of women in the sports coaching field.

September 21, 2022

While athletes are often at the center of discussions about gender disparity in sports, the coaching industry frequently lacks the same attention. A Burlingame-based organization has their sights set on tackling this issue — and it all starts with supporting female coaches.

The Women’s Coaching Alliance’s (WCA) central mission is to grow the presence of women in the sports coaching field. They offer mentorship and coaching opportunities to aspiring female athletes, equipping them with the knowledge, skills and confidence to enter the professional world.

According to WCA founder Pam Baker, their initiative stretches beyond just coaching.

“The idea [is] that more young women not only get a chance to coach, and more kids see women as leaders and role models, but also [that] coaching skills are leadership skills,” Baker said. “More young women head out into careers and lives with the leadership skills to be able to lead, but also the confidence to know that they can.”

Baker created the WCA to honor and preserve a legacy. In May of 2020, her husband Doug Friedman was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He passed away in the following months. Friedman was an experienced coach and a father of two daughters.

“He was somebody who not only believed in great coaching, but was a real advocate of pulling women off the sidelines to help him coach — particularly because he was coaching girls and recognized he didn’t know what it was like to be a girl,” Baker said.

Members of the WCA voiced a similar sentiment — having a female voice at practices and games can make a major difference. Senior Emmi Cate joined the WCA in July and is working towards being a coach for younger girls playing soccer.

“There is a different kind of connection,” Cate said. “[Female coaches] understand you more, what you’re going through, the situations you’re in and how to deal with them.”

Inspired to bring this sense of empathy to more teams, Baker founded WCA with two goals: to give girls the confidence to lead, and to change the way younger generations view women leaders.

“[It’s] getting more kids to see women as leaders as the norm as opposed to the exception,” Baker said.

Although Baker was involved in sports as a teenager, she admits that she was never a standout player. But by meeting and hearing from many coaches later down the line, she learned that a team’s best athletes don’t necessarily make great coaches. Sometimes, players used to occupying supporting roles make the best mentors and leave a lasting impact.

“The ones on the bench, when you have the right team of people, add a whole different element that lifts the entire team up,” Baker said. “I think oftentimes, it’s the kids who are serving a really important role on the team, but might not be the stars.”

WCA jump-started their initiative by recruiting female athletes and pairing them up with mentors. The program is structured to give budding coaches hands-on experience while mentors guide them in the right direction. A coach mentor teaches the technical aspects of leading a sports team, and an additional mentor ties their coaching experience to career skills.

“Me and my partner are supposed to be the ones that organize everything, and then [the mentors] are there just to supervise,” Cate said. “But we can ask them for help and assistance, and these are grown adults that have experience and know what to do.”

The organization partners with other athletic associations like Burlingame Parks and Recreation and the American Youth Soccer Organization (AYSO) to send women coaches and mentors to oversee their youth sports programs.

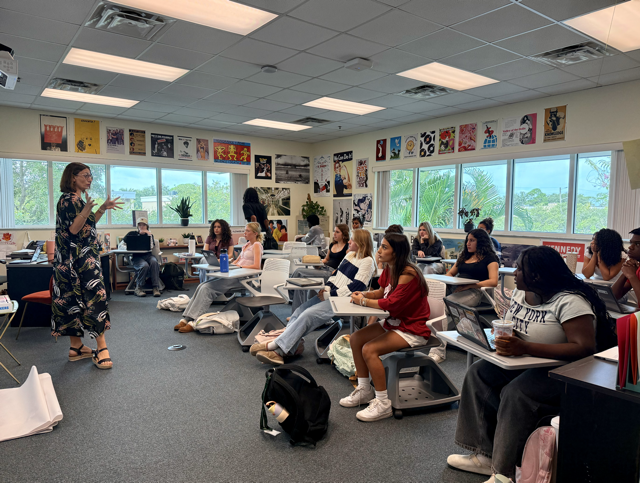

The WCA hosted a convention at the Burlingame Community Center on Aug. 13 that featured a coaching and career panel. Panelists Donna Coleson, Jacquie Cooke, Dani Langford, Richard Moran and Kim Turner led a discussion on the importance of coaching and its connection to leadership. Participants explored how coaching experience could open the door to other career pathways.

“I think that everyone that’s supporting [the WCA convention] has such great intentions, and they have a lot of energy behind it,” said Crystal Gibbon, who is an assistant coach of the varsity girls’ basketball team at Burlingame.

Gibbon attended the WCA panel after hearing about it in a newspaper. She realized that the organization aligned perfectly with her personal motivations to coach.

“[Every] reason why I’m coaching, just everything, checked every single box,” Gibbon said.

Izzy De Oliveira, who graduated from Burlingame in 2019 and was an assistant coach on last season’s freshman girls’ basketball team, also attended the convention after hearing about it from another coach.

“It was really cool to see a room filled with women leaders,” De Oliveira said.

Baker’s emphasis on community outreach is inspired by a book called “The Confidence Code” by Claire Shipman and Katty Kay, which explores how from a young age, girls’ confidence drops while boys’ confidence increases. She explains that boys have a greater tendency to adopt an “I’m going to try it” attitude without fear of failure, while young girls hesitate to take chances.

“I found this throughout the course of my career — women hold ourselves to this ridiculously high standard,” Baker said. “If we haven’t done 97% of the job, we will not put ourselves out there.”

At the WCA, Baker’s hope is to simply give women the opportunity to try, regardless of whether they stick with coaching in the long-term.

“[Women] understand that coaching is leading, so they are able to confidently speak to that experience and show up with the confidence that they have absolutely earned by leading,” Baker said.

Baker also stressed that all it takes is one push to dissolve initial hesitation toward coaching — whether that push comes from a coach, friend or family member.

For Cate and Oliviera, the push came from coaches they looked up to in their youth.

“I had a previous coach that I really looked up to reach out to me,” Cate said, encouraging her to join WCA.

“My coach Jeremy…he’s the one that asked me to coach, and I never really thought about it,” Oliveira said. “He’s the one that really inspired me to want to coach and then I ended up really liking it.”

At the end of the day, the problem isn’t as complex as it seems, according to Baker. Growing the number of women coaches ultimately boils down to providing encouragement and taking initiative.

“It’s not rocket science. I think oftentimes, we think there’s got to be many more programs around it,” Baker said. “[But] sometimes it’s just to say, ‘Hey, will you coach with me?’”

This story was originally published on The Burlingame B on September 6, 2022.