Christa Dutton

Lydia Swortzel (left) and her husband, Stevien Reece (right) hold their baby, Oliver.

How a mother’s choice saved her child

Wake Forest alumna Lydia Swortzel recounts a heartbreaking medical decision she made while pregnant, which resulted in the loss of one son and the life of another

When Lydia Swortzel and her husband Stevien Reece found out they were having twins, they were shocked.

They were shocked not only because carrying two babies at one time is daunting but shocked all the more because they had only one embryo implanted through in vitro fertilization (IVF).

“Did we transfer two embryos?” the specialist at her local Winston-Salem fertility clinic asked Swortzel as she lay on the examination table.

“Uh, no,” Swortzel replied.

“Well, there’s two in there. Twins.”

The one embryo they had implanted had naturally split into two, resulting in identical twins.

Swortzel said the rest of the visit was a blur. They walked out of the office, got into the car and then started — laughing. It was ironic; from the moment they found out they were pregnant, Swortzel and her husband joked that they would be alright — as long as they didn’t have twins.

“Then after [the laughter], we were just terrified,” Swortzel said.

As a self-described type-A planner, Swortzel began calculating all the doubled costs of having twins — double the clothes, double the diapers, double the attention. She even thought as far ahead as when they would be paying double the college tuition.

Swortzel was in the middle of Wake Forest University’s MBA program at the time. She wouldn’t finish her degree until after she delivered the twins.

Despite her apprehension about finances and still being a student, Swortzel was happy about being pregnant. The longer she carried her babies, the more excited she felt. She delayed buying anything baby-related, however, because she knew the chances of miscarriage were high. Swortzel was 35 at the time and becoming pregnant had not been easy. In fact, Swortzel and her husband had only told their families about their pregnancy just in case something went wrong.

Emergency

One Monday morning, when Swortzel was 21 weeks along, she decided it was time to announce her pregnancy. But before she and Reece had the chance to tell anyone, Swortzel felt some pain she had never felt before, and her husband immediately took her to her doctor.

The doctors did a scan and rushed her to the emergency room. The two babies were trying to come out, but they were only 21 weeks along — way sooner than Swortzel expected.

The doctors couldn’t perform a traditional cesarean section because of where Baby A — who Swortzel and Reece had named Winston — was located, so they had to perform another delivery method that posed a much greater risk for both the babies and Swortzel.

The doctors told her that there was no way to perform this surgery without inducing labor for Baby B, named Oliver. If delivered, both babies would have a zero percent chance of survival. The life-saving equipment like IVs and breathing tubes used on premature babies would not have even fit them since they were so small, each under one pound. Both babies were likely to die or have a quality of life so poor that Swortzel and Reece would not want that for their children.

The other option was to wait to deliver until she had reached 24 weeks of pregnancy, the most commonly accepted week of viability for newborns. With this option, Winston’s survival was unlikely because, where he was located, he was cut off from oxygen and amniotic fluid. Winston would be born only to shortly pass away. His brother, however, would have a fighting chance.

Swortzel and her husband were faced with an incredibly difficult decision — a decision her doctor said she would not have in some states.

“The doctor told me that in some states, the distress and the life of the babies come first — regardless of if I was scared of the surgery because I had a higher mortality rate and regardless of if [the babies] would survive,” Swortzel said. “They based it off a hope they can survive.”

Swortzel looked at her husband and told him she didn’t want to die.

The Choice

After a few sleepless nights, many tears and prayers, the Swortzels decided to go with the latter option — to wait until 24 weeks, knowing that Winston would die shortly after birth, but Oliver would have a much higher chance of surviving.

On a Wednesday, Swortzel hit 24 weeks. Less than 48 hours later, her babies were born.

Oliver was rushed to the NICU, and he was administered the Apgar test, which measures how much life there is in an infant. The exam measures the newborn’s skin color, heart rate, reflexes, muscle tone and breathing rate. Overall, the best possible score a newborn could receive is a 10, although few do. Oliver scored a one. Winston, a zero.

While Oliver was carried away to be treated, Winston remained with his parents. He had a faint heartbeat, but he had been without oxygen for too long.

Swortzel held Winston in her arms as he passed. Before he died, her husband carried him to the window to show him the sunrise — the sun illuminating a world he would never experience.

They slept that night at the hospital with Winston in a crib beside them. The nurse told them to call when they were ready for the nurses to take him. “Ready?” Swortzel thought. “How can anyone ever be ready for that?” Crying, Swortzel called the nurse and watched her take him away.

The Swortzels describe Winston as “his brother’s savior” and “their little hero.” They think about him ever day and desperately wish he were with them. Still, they are thankful for the choice they had. Swortzel says her right to choose her medical treatment resulted in Oliver’s life.

“We’re very lucky,” Swortzel said. “I say that and a lot of people respond, ‘Oh really, are you? Because you lost a baby.’ But we really are because we could have lost two babies. I could have been forced to deliver both of them and never gotten to know either of them.”

Oliver stayed in the NICU for 123 days. He was still very sick, but persevered. Today, he is 18 months old without any health issues and is meeting all the milestones.

Background

Lydia’s case and others like it are grounded on the legal debate regarding compelled medical treatment of pregnant patients. Common and constitutional law grants every American — including pregnant ones — the right to refuse medical treatment. However, pregnant patients can be forced by court order to receive medical treatment or be found criminally or civilly liable for any injury or death to a fetus caused by the refusal of medical treatment. Swortzel’s doctor was likely referring to exceptions like these that limit a pregnant patient’s options. One such case occurred in New Jersey in 2006, years before Swortzel became pregnant.

A New Jersey woman who is only known by the initials “VM” in legal documents gave birth to a little girl we only know as “JMG”. VM’s doctors advised her to consent to a cesarean section because her fetus was demonstrating signs of distress, much like Winston. VM refused. JMG was safely born by vaginal delivery and all was well — until the Division of Youth and Family Services (DYFS) learned of VM’s refusal to consent to the c-section.

DYFS also discovered that VM had not been forthcoming about her diagnosis or being under psychiatric care for 12 years before giving birth to JMG. VM’s husband, BG, who is also only identified by his initials, refused to cooperate with DYFS when they tried to obtain information.

DYFS sought a Title 9 — not to be confused with Title IX of the Civil Rights Act — pursuant to the Abandonment, Abuse, Cruelty and Neglect Act (NJSA 9:6-8.21 to 8.106) and took JMG into their custody. After a hearing, a judge found that JMG was abused and neglected in part because her mother failed to cooperate with her doctor. Other reasons cited for taking custody of the child was VM’s psychiatric history and her erratic behavior post-delivery that suggested she and her husband would not be fit parents. At a permanency hearing, a judge approved DYFS’s plan for termination of parental rights and family adoption.

This case serves as evidence that if Swortzel had delivered in another state then she may have been forced to do whatever her physician ordered or face the consequences of not listening. In North Carolina, there is no legal precedent for compelled cesareans. For Swortzel’s doctor to have forced her to deliver at 21 weeks, he would have had to appeal to the North Carolina court system to procure a court order demanding that Swortzel deliver.

However, her doctor did not file a court order. Instead, Swortzel had the privilege of making a decision.

Protest

Since Swortzel was able to make an autonomous decision regarding her reproductive care, she worried when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey in June.

“When Roe v. Wade was overturned, I knew the implications it would have for people who wanted abortion access just to have abortion access, but also [I knew the implications] for people like me who had to make an unthinkable medical decision,” Swortzel said. “Now, that decision may be taken completely out of their hands.”

Associate Professor of Law at Wake Forest University Meghan Boone, whose expertise lies in reproductive rights, explained why Swortzel is justified in being concerned about how the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision impacts medical decision-making while pregnant.

“Roe explicitly protected the right to abortion, but underpinning that right was the idea that pregnant people had the right to make medical decisions about their own bodies, even if those decisions interfered with the health or life of the fetus they carry, at least as long as the fetus was not yet viable,” Boone said.

In the case in New Jersey, Roe v. Wade did not protect VM because the fetus was far past the point of viability.

“In a world without Roe, pregnant people like Lydia could be forced into medical treatment or decisions even with pre-viability fetuses, like her twins were when she went into premature labor,” Boone said.

In addition to abortion access, Swortzel wants people to consider how abortion rights affect those who do want children.

“I want people, especially when they’re thinking about Roe v. Wade, to think about how it affects more than just people that want to go out and have an abortion because they don’t want a child,” Swortzel said. “[Some people] didn’t want to have an abortion. They didn’t want to have a late term loss. They didn’t want to make a decision like this. But they have to — in order to have a life on their own, to be able to give another baby life or in order for a child not to suffer, they have to.”

Swortzel took her concerns and turned them into activism. She was among the 1,000 people that gathered in downtown Winston-Salem to protest the reversal of Roe v. Wade.

The protest was on July 3. The next day, many Americans celebrated Independence Day. That day, however, protesters took to the streets to express that they felt one of their freedoms had been taken away.

Almost every protester brought a sign along with them. Some of the poster slogans included:

“WOMEN’S RIGHTS ARE HUMAN RIGHTS”

“THEOCRACY IS UNAMERICAN”

“KEEP YOUR ROSARIES OFF MY OVARIES”

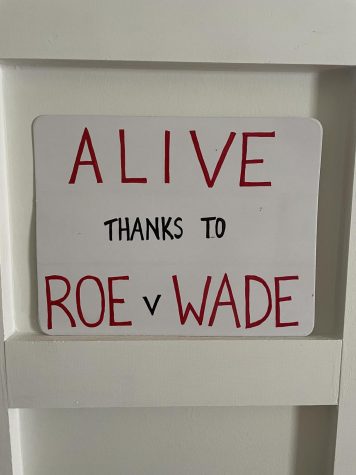

The Swortzels marched with Oliver in a stroller. They also brought a sign, hanging it on the back of the stroller. It read: “Alive thanks to Roe v. Wade.”

This story was originally published on Old Gold & Black on September 26, 2022.