Destination: West

West High’s immigrant community shares their hardships and ambitions while reflecting on the experience of migrating to a new country.

November 18, 2022

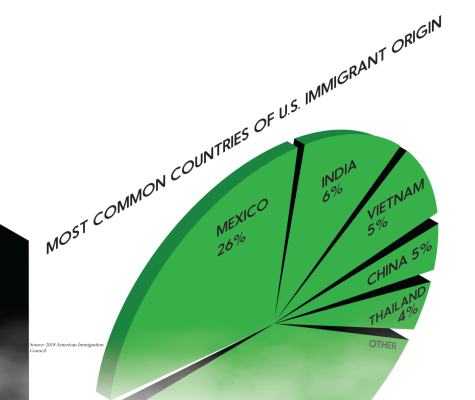

Immigration can be a difficult process, with immigrants facing hardships such as navigating complex legal systems, leaving friends and family behind and sometimes learning a new language. However, hope for a new life continues to influence individuals to migrate all over the world. For some, their journeys have brought them to West High.

The Journey

While most immigrants seek a better life when moving to a new country, motivations behind the move are different for each person. Economic opportunities play a major role for many, including Didier Kasongo ’23 and his family who emigrated from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the U.S. in 2018.

“My parents came here first [and sent] money to me, so I could come,” Kasongo said. “[In the DRC,] we didn’t have money, and then when we came here, everything changed … Better jobs, better money, better life.”

Others make the journey to pursue alternative educational opportunities. Isabel Garcia Rascon ’25 came to the U.S. from Mexico at the start of the school year. She believes this education will give her better opportunities in the future.

“I came here because I wanted to learn English, but I plan to return to Mexico,” Garcia Rascon said. “Learning English opens more doors in Mexico — more work and more schools.”

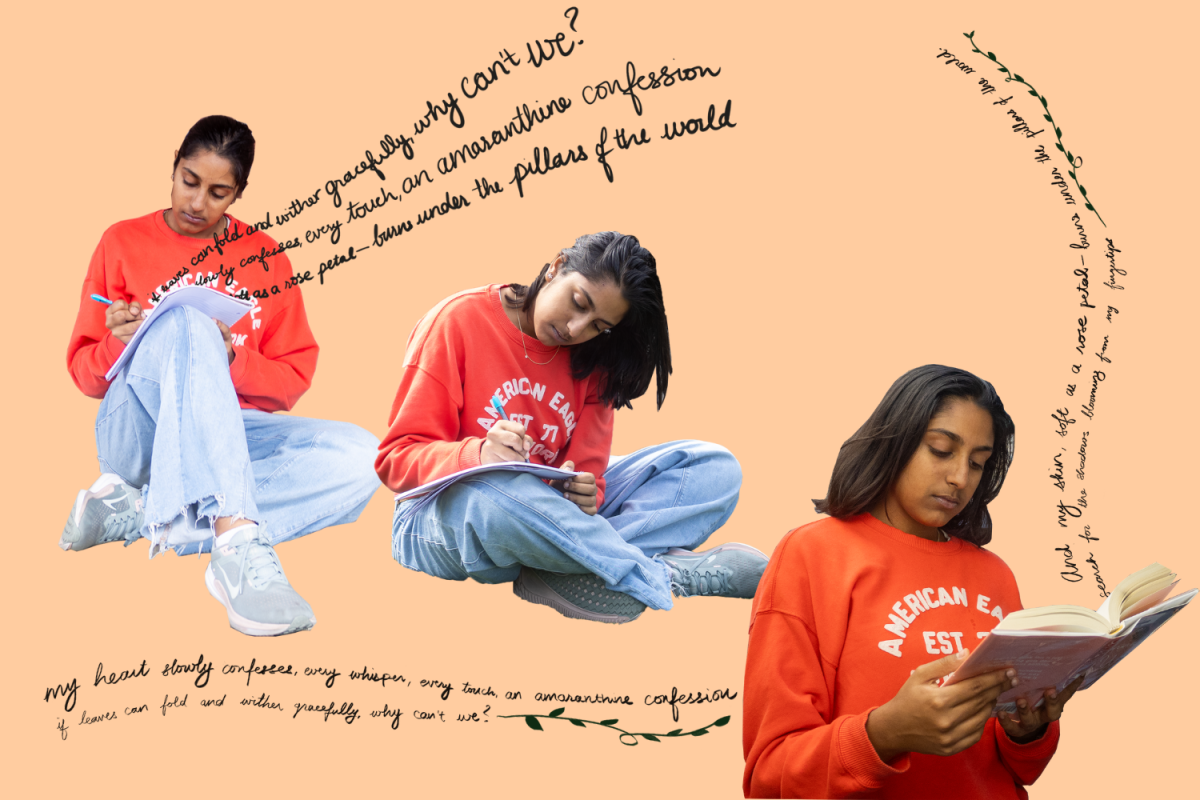

Nomi Wang ’23 emigrated with her mother from China right before this school year for better educational opportunities as well.

“[My mom was] always talking about [how] she [wanted] to send me to either [an] international school in Shanghai or just wanted me to come to the U.S. as soon as possible, so when she told me, ‘Hey, you have the chance to come with me to Iowa,’ [I took] it,” Wang said. “I think America will be a better place for my own development, both in academics and other stuff.”

Chances for economic and educational growth can also be a push for people to emigrate from the U.S. to another country.

After spending the first 10 years of his life in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Bashir Eltyeb ’25 and his family decided to move to the United Arab Emirates. Since then, they immigrated to Sudan and then ultimately returned to the U.S. Employment was the deciding factor in Eltyeb’s family’s first move.

“My parents left the U.S. to go to the UAE because [of] jobs, basically,” Eltyeb said. “My dad is an electrical engineer, and the UAE is still a growing country … So there’s a high demand for [electrical engineers].”

Additional opportunities aren’t the only factors immigrants take into consideration. According to Eltyeb, family was the main reason his family went from the UAE to Sudan.

“Sudan is our home country,” Eltyeb said. “My extended family is all there like my grandma, my uncles, my aunts. Some do live here, but most of them are back there.”

Eltyeb and his family moved back to the U.S. from Sudan this August due to political instability.

“At the end, safety issues from crime forced us out,” Eltyeb said. “I got beat up by the military. One time we got robbed, me and my friends. We got a machete pulled on us … I told my parents, and they were like, ‘Yeah, this is not a place we can stay.’”

Forced migration occurs when a person moves to avoid conflict, violence or natural disaster. Immigrants who have experienced forced migration are refugees, but the requirements for official refugee status and being granted asylum vary from country to country.

University of Iowa professor Bram Elias leads the Immigration Advocacy section of the University of Iowa Legal Clinic, which provides free legal representation for people who need it. According to Elias, in order to qualify for asylum in the U.S., the individual must have a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.

“Being afraid of being persecuted or tortured or having something really bad happen when you go home, that’s part of what you need [to get asylum]. But, that’s not all of what you need,” Elias said. “It turns out that for the law, why you are being persecuted matters a lot.”

For those looking to become a lawful permanent U.S. resident, three other ways exist: the Diversity Visa Program, employment sponsorship or family relationships. The Diversity Visa Program is a lottery that grants permanent residence to 50,000 immigrants annually from countries with low levels of immigration.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, the most common pathway is through family relationships, with 45% of green card holders in 2020 being immediate relatives of a current lawful permanent resident.

“If you have a close family connection to any U.S. citizen or sometimes a green card holder … you can use that family connection, and that’s a way for you to apply for a green card,” Elias said.

After obtaining a green card, immigrants can legally stay in the U.S. for as long as they want, but they are not yet U.S. citizens.

“Once you stay here for a period of time, usually five years, then you’re eligible to apply for citizenship,” Elias said. “You take a naturalization test to see if you speak English well enough and if you know enough about American history. Then if you pass the test, you take an oath. Then you’re a citizen for the rest of your life.”

The Immigration Advocacy section of the University of Iowa Legal Clinic works on all types of cases regarding U.S. immigration and the naturalization process.

“There are some cases where the government’s trying to deport someone from the United States, and winning is stopping them. There’s other cases where one of our clients has a complicated path from where they are right now to becoming a citizen, but they want to become a citizen,” Elias said. “We’re not fighting against the government. We’re just helping [immigrants navigate] the process.”

The Arrival

The journey to the U.S. and becoming a lawful permanent resident are only half the battle. The adjustment to life in a new country is difficult. For some, the people back home are what they miss most about leaving their country.

Garcia Rascon traveled to Iowa alone and has been living with her aunt and uncle ever since.

“[My parents] stayed in Mexico. It’s difficult because I have brothers, and I have more family in Mexico, and I miss my family,” Garcia Rascon said.

Polina Avdonina ’26 immigrated to Iowa from Kazakhstan a year ago and has found keeping in touch with her old friends difficult.

“Missing my friends [is a challenge]. When you are far away from your friends, [it’s hard to keep in contact], but we still sometimes talk,” Avdonina said. “[The time difference] is 10 hours apart.”

The language barrier that numerous immigrants face adds to the challenge of making friends in a new country.

“[When I found out I was coming here], I was kind of sad because I didn’t let some people know that I was coming here. It was just a surprise,” Kasongo said. “When I came here, I was kind of shy in middle school. So I was just going to learn English first … When I came to West, I started speaking.”

Garcia Rascon agrees that it takes a lot of bravery to reach out to new people.

“[Making friends] was difficult. I had to dare to speak the language; [then], for the most part, people could connect,” Garcia Rascon said.

Language acts as a barrier in more than just friendships, which is why the English Language Learning program exists. Upon enrollment in the Iowa City Community School District, if a family indicates on the Iowa Home Language Survey that a language other than English is primarily spoken at home, they are required to take the English Language Proficiency Placement Assessment per Iowa law. ELL eligibility is based on the results of this test, previous English language assessments, past academic records and interviews with parents.

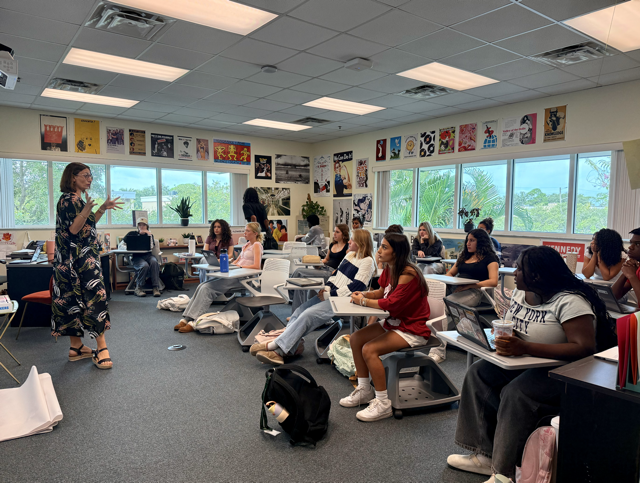

In the 2021-22 school year, 12.9% of students in the district were ELL-eligible. Jessica St. John, an ELL teacher at West High, explains what students learn when they attend an ELL class.

“[During] day-to-day class, we would start off with vocabulary, and then do a reading strategy … Then we’d read, and we try to use the reading strategy. Then, we talk about it and then try to answer questions,” St. John said. “A lot of times, [ELL students] develop speaking skills so early, before writing skills, so they’re pretty good at communicating verbally. A lot of our students you wouldn’t even know are [in] ELL.”

While teaching English is the primary function of the class, ELL teachers help their students with much more than just their language skills.

“My job is teaching English, but also teaching kids about the culture here and then advocating for them in their other classes to make sure they’re getting the right help, and just helping them with life,” St. John said.

In the ELL classroom, the shared experience of the language barrier has allowed many students to form connections.

“Communicating and making new friends [was hard],” Avdonina said. “[ELL] helped with English and with finding people.”

St. John has noticed ELL students feel more comfortable socializing with each other.

“I think it would be great if they could socialize with more people, especially outside of their own demographic and their own language group,” St. John said. “But there’s that language barrier. Sometimes they get comfortable in their cliques just like [non-ELL] students.”

St. John wishes ELL students had more opportunities to talk to people outside of their established social groups, especially underprivileged students.

“After-school activities like sports [would] help their social lives, but then comes into play transportation, cost of sports, uniforms — all those things that we as people who grew up here take advantage [of] or take for granted,” St. John said.

English courses can also be uniquely challenging for immigrants.

“Most of the subjects [are] fine for me. Only literature is a little bit hard. You have to learn some terms in English, and you can’t find the exact Chinese definition of it,” Wang said.

Besides providing ELL to help students improve their English, the ICCSD also helps English language learners with their courses by offering “sheltered” versions of regular courses. These classes have a core curriculum teacher working alongside an ELL teacher.

“The idea is to help the teachers, who have generally always taught kids who are already fluent, help them teach ELL [students],” St. John said. “[The teacher I work with] knows math way better than I ever will, and I know ELL, and so if we work together, then we can try to help the kids the best we can.”

Other resources are available for immigrants to learn English, such as private tutoring services or the Friendship Community Project, an organization whose goal is to help immigrants in the Iowa City Area learn English. Wang used private tutoring to prepare for the Test of English as a Foreign Language.

“U.S. universities will ask you for your TOEFL test score,” Wang said. “I [have] four tutors; one is for reading, one is for listening, one is for speaking and one is for writing … It does help me a lot.”

Another way immigrants at West speed up their language-learning process is by consuming content in that language.

“Outside of school, I read books, and I listen to music in English … I watch Marvel movies, and I watch programs [for] children, but I learn new words,” Garcia Rascon said.

Most immigrants expect to face the language barrier, but many cultural differences come as a surprise.

“In [the] Congo, we will usually use books, math books, and here we have computer stuff — fancy stuff. In [the] Congo, we didn’t have this stuff,” Kasongo said.

While the educational resources are different, Wang also found the social environment of school in America different from China.

“I tried to make a TikTok video with my teammates yesterday because we were shooting [hoops] … They just invited me to be involved in their TikTok. I’m not such a confident person to do such things, like expressing myself. I always think that students in America, they’re really confident about themselves. [Everyone] wants to share their own opinions and express their true self,” Wang said.

Cultural differences can also lead to misunderstandings; information one party communicates can be perceived differently by another party.

“[My teacher] says things like, ‘It’s only seven days before the midterm,’ and I just think maybe midterm is some kind of test because midterm means test in China,” Wang said. “At the time, I was a little bit stressed because I just [saw] the [word] midterm and these seven letters just [freaked] me out. [When] the midterm actually [came], I found out, ‘Wow, there’s no test.’”

While the effects of these cultural differences are usually harmless, some can cause serious issues. Immigration and Refugee Community Outreach Assistant for the Iowa City Police Department Joshua Dabusu came to Iowa from the DRC in 2016. Dabusu acts as a bridge between the immigrant community and the police to facilitate trust between the two groups.

“Policing in Africa, it’s very different, it’s very brutal … Imagine if somebody who [has] experienced this kind of stuff in their country comes here — [When they see the uniform], they try to process it like, ‘What is this person gonna do to me?’ So they are already going through a crisis, and if you don’t know how to interact with them, you’re just creating another issue,” Dabusu said.

West High provides cultural liaisons to help teachers and students navigate issues caused by these cultural differences.

“If we have a cultural liaison, and there’s a problem at home, they can kind of take the cultural experience, and take that into consideration and be like, ‘Hey, in our culture, this is how we deal with death.’ Right? And so maybe [the student] needs three or four days. They can just give us advice about what that student [needs],” St. John said.

Eltyeb believes it is important that students are understanding of cultural differences and provide help without being patronizing.

“There needs to be a balance of bearing with us, but also not underestimating us,” Eltyeb said. “Bearing with us in situations where people are like, ‘You don’t know what this is?’ and I’m like, ‘No, I don’t, it wasn’t a thing back home.’ … But at the same time, I’ve realized there are a lot of people that treat us like we don’t know anything, which is also wrong.”

The Future

Life takes people down many unexpected roads, and this was the case for West High Spanish teacher Javier Montilla. Montilla returned home to Venezuela after his university studies in the U.S. ended, but decided to move back to the U.S. when Venezuela was going through unstable times.

“I never planned on staying [in the U.S.],” Montilla said. “[But] what happens with immigration [is] when you decide to move to another country, [it is because] things are going so badly in your [home] environment or in the country as a whole.”

For many immigrant parents who escaped a hard life in their previous country, it is rewarding to provide their children with opportunities they didn’t have. Rosa Villanueva, head cook at West High, started working when she was seven years old in Mexico. She believes that the difficult move from Mexico to the U.S. was worth it in the end.

“It’s hard when you are poor. You don’t have the opportunity to have a car. You don’t have the opportunity to go to the theater to see a movie,” Villanueva said. “This country brings me a lot of happiness because I see my daughter [get] this stuff I [thought about] when I was a little girl.”

Esther Zhang, Wang’s mother, sees Wang’s future as having more possibilities now that they live in the U.S.

“A lot of Chinese students think they don’t have a future because in China, there aren’t many opportunities, and they are pessimistic because their parents are very disappointed in them. I think the future is hopeful for Nomi [after moving],” Zhang said.

Wang already has an idea of what this future may look like.

“I lost three years of traveling because of the pandemic [and lockdown] in China. I want to compensate myself a little bit in the following years, just go traveling and see people from different nations,” Wang said. “[I also want to attend] the university here to continue my studies.”

Eltyeb also sees education as an important part of his future, as well as pursuing his interest in programming.

“I want to graduate from West High and go to a really good university somewhere in the U.S. … I want to be a computer engineer,” Eltyeb said. “When I was living [in Sudan], I was really starting to get into programming, but I could never download these things because the internet is limited.”

While settling into a different place is strange and discomforting, the West High community plays a large role in helping students adjust.

“Everybody in school that I [meet] are all friendly and kind to me,” Wang said. “When I need something academic, my counselor will stand up and help me, and when [I] feel like I don’t have [many] friends, someone in class will show up and be like, ‘How’re you doing?’”

However, there are still things the community can improve on. St. John thinks it is important for other students to be aware of the privileges they have as individuals who grew up in the U.S.

“[PALs] come in and do conversation partners and try to get [ELL students] to talk about different topics and meet people. So that’s kind of fun. But then it’s like the students aren’t prepped … Some of the students are very affluent or their families are rich, and so they ask students, ‘Where’d you guys go for spring break this year?’” St. John said. “I feel like as a school, we don’t do a good job of saying, ‘Hey, this is who’s in our school.’ Some people come in, [and] they’re like, ‘I had no idea that there were classes like this.’”

While generally inclusive, some in the West High community are ignorant about the experiences of immigrants.

“I feel like people just underestimate immigrants … at certain times, some people would speak slowly, assuming that we do not speak proper English,” Eltyeb said.

When cultural differences become frustrating to navigate, it can be comforting to have a space where people with similar backgrounds can connect.

“I really like the concept of the [Sudanese Student Organization] because it’s bringing people who are like me together, people of the same culture,” Eltyeb said.

Along with finding community, Montilla encourages immigrants to invest time in themselves and dream big.

“Everybody can have a different version of the American Dream and what you can do in this country,” Montilla said. “[When you arrive], you realize that not everything is like what they told you, but on the other hand, there are so many opportunities. You can accomplish anything if you have the right disposition, and you look for the skills to accomplish what you want.”

This story was originally published on West Side Story on November 17, 2022.