50 years later: Title IX’s impact on Algonquin

Photos 1961 & 1975 yearbook, Harbinger archive, Graphic Katherine Wu

Title IX passed 50 years ago, in June 1972. Since then, it has tremendously impacted girls’ sports at Algonquin.

December 9, 2022

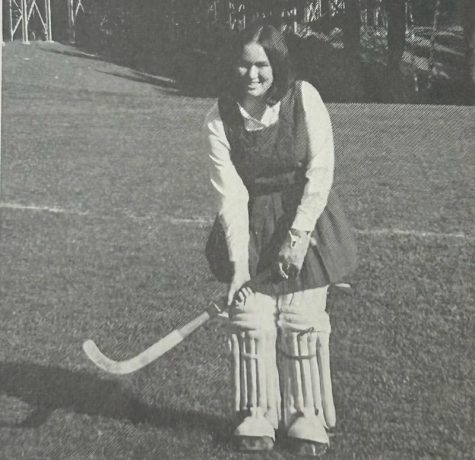

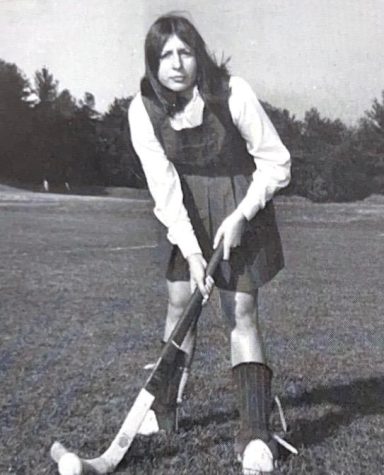

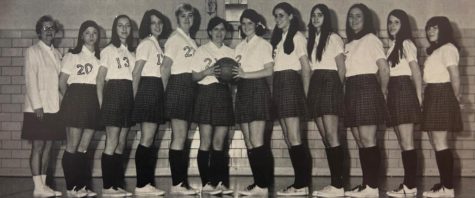

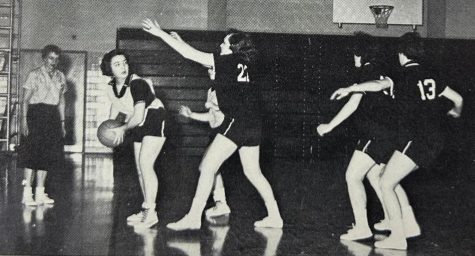

Today, whether playing on a girls’ or boys’ team, Algonquin athletes wear their Titan uniforms with pride, putting in long hours on the field, court, track or mat, competing at the top level and striving for State Championships. However, flipping through yearbooks from the 1960s and 1970s shows another story. There were significantly fewer girls’ teams than boys’. Not only did uniforms look different, with many of the girls wearing skirts, but as athletes from the 1960s say, the focus for girls was less on competition and more on just having fun. That all began to change fifty years ago in 1972.

In June 1972, President Nixon signed Title IX into law, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex in education and athletic programs. This law changed female athletics at Algonquin forever.

Today, 50 years later, Algonquin has 16 varsity girls’ sports teams and in the years since Title IX went into effect, girls’ teams have won a total of 10 State Championships. However, change wasn’t immediate. The history of women’s athletics at Algonquin is extensive and complex.

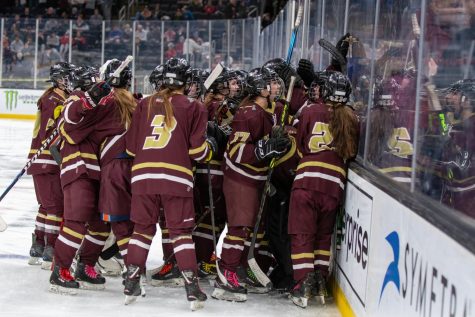

When Title IX was first signed into legislation, Algonquin offered more sports for girls than many other area high schools. However, the only sports offered for girls at ARHS were field hockey, basketball, cheerleading, softball and tennis. Although there was boys’ hockey, track and golf, these weren’t options for girls. In fact, girls’ hockey, which won the State Championship in 2022, became a varsity sport in 2003 and girls’ golf in 2017. Both teams are currently collaboratives with area schools.

Past Athletic Inequities

Class of 1971 alumna Patti Fouracre Serafin played field hockey, basketball and softball at Algonquin. She remembers not only were there fewer sports, but some sports, such as basketball, were played with significantly different rules.

“When I started playing basketball my freshman and sophomore years, the girls didn’t play like the boys played,” Serafin said. “The boys played with five players running up and down the court while we played with a six player formation and many different rules; there was an offensive and defensive end and depending on your position, you could only stay on one side, with two rovers that could play on both sides.”

Class of 1962 alumna and member of Algonquin’s sports Hall of Fame Stephanie Slack, who played field hockey, basketball and softball at Algonquin, recalls that boys’ teams were allowed to practice on the gameday court significantly more than the girls’ team.

“The one gym that we played our games in was pretty much dominantly used by the boys’ team,” Slack said. “We could only get on the gameday court every once in a while, and when we did, the boys’ team made it seem like they were doing us a big favor.”

However in 1971, even before Title IX went into law, girls’ basketball switched to the same five vs. five formation as the boys’ team and were undefeated, with a record of 12-0, winning the title of Midland League Champions.

“Our senior year, the team was invited to a tournament, and not very many teams prior to us went to the tournament,” Serafin said. “It was the Southbridge High School Girls’ Invitational Tournament, and the first round was a bye due to our impressive undefeated record; however, we were defeated in the second round.”

Serafin remembers discrepancies between playing conditions and fields for baseball and softball as well, which impacted and limited fans.

“For baseball, there were bleachers for the fans but for softball there were no bleachers, not even a little portable set of bleachers; people would have to bring their own chairs,” Serafin said.

At Algonquin now, both the baseball and softball diamonds have bleachers for fans and viewers to watch.

Another difference that impacted fans and gave priority to boys’ teams, was the timing of girls’ and boys’ games; however, now they occur at similar times.

“The boys played at night and the girls played right after school,” Serafin said. “The majority of people attending a girls’ game would be parents or friends, not like the general population of the student body like when you went out to a boys’ game, which had the pep club people that would sit up in the stands.”

Progressive Nonetheless

Although boys’ and girls’ athletics weren’t entirely equal before Title IX was passed, Slack says Algonquin was progressive compared to neighboring schools.

“We were lucky at Algonquin; we were really ahead,” Slack said. “We had good uniforms, we had good equipment and we had a coach that advocated for us and got us games and transportation and officials. Algonquin really put some value on girls athletics, certainly not how it is today though. When I left Algonquin after seeing some other programs at other schools, I realized that Algonquin really did a good job before Title IX that didn’t technically have to be done.”

Athletic Director Mike Mocerino, who was an ARHS athlete and coach, believes the school has done a good job in providing equal athletic opportunities for girls and boys.

“As a former student-athlete from 1996-2000, and then coach from 2006-2017, I believe Algonquin has gone above and beyond to ensure that both genders have equal opportunities through interscholastic athletics,” Mocerino said. “Today, we offer up to 58 total sports teams, most with three levels depending on the sport and participation numbers. We offer 16 sports for our boys and 16 sports for girls. And, even though high school girls’ participation in athletics has grown, there is still room to grow.”

Then vs. Now

In the 1960s and 1970s, many girls went into high school with little experience in sports, oftentimes not playing a sport until high school.

“One of the things about growing up in Northborough was that there wasn’t anything for girls before you got to high school,” class of 1971 alumna Janet Faucher Cooley, who played field hockey, basketball and softball at Algonquin, said.

According to Serafin, virtually everything started for girls athletically in high school.

“There were no community sports like Little League for boys,” Serafin said. “The closest thing we had to a community based sport was when Father Cahill at St. Rose of Lima came and started a lassie league, which was like slow-pitched softball, in junior high. We wore denim pants, called dungarees, and white blouses, and we didn’t know who was on what team because everyone wore the same uniform.”

Now, there are a myriad of intramural sports opportunities available for young girls, so many athletes come into high school experienced.

“I think it was great to watch the progress of it [female athletics] evolve into more,” class of 1970 alumna Rosemary McGowan said. “The great thing is as kids went into college and were good at their sport, it opened up doors for anybody to have it be equal.”

When McGowan was in high school and played field hockey, she noticed that people displayed a different attitude towards girls and boys sports.

“There really wasn’t much emphasis being a female on a sports team,” McGowan said. “They were not recognized as they are now. My great niece was a very good softball player and everybody knew, but I don’t think anyone knew, outside the softball team and coaches, that we were part of a sports team. If you were on the football team, everyone knew.”

According to McGowan, athletics then were treated as after school clubs rather than varsity sports.

“We didn’t know better than that it was an after school activity; our expectations at that time weren’t that we should have more people there,” McGowan said.

Due to Title IX, sports are taken more seriously now, leading to more opportunities for women to compete beyond high school.

“Title IX opens doors for women,” McGowan said. “So many years later, I saw what it did for my [great] niece, who got a scholarship to college for pitching. It was wonderful to see.”

Another factor that contributes to the success of female athletes in high school to ultimately play at the collegiate level is increase of resources and programs.

“Nowadays, athletes have conditioning classes before their sports season, are in the gym working out, going to clinics, have private coaches and athletic trainers,” Serafin said. “We didn’t have any of that. We just showed up and played; it was not as rigorous as today’s women’s sports are.”

A Coach’s Perspective

Slack began coaching field hockey, fencing and softball in 1969 at Milford High School, before Title IX was passed.

“Milford virtually had nothing, no PE class for girls at all, so when I took the job I agreed to start a PE and field hockey program,” Slack said. “The girls didn’t know what field hockey was; we didn’t have a field and only had some equipment. I had to beg for everything, from uniforms to equipment. I can remember drawing lines in the dirt to coach the field hockey team. Title IX was passed, and all of a sudden things started to develop much more quickly, including coaching salaries.”

According to Slack, Title IX caused mixed feelings in the school, with some people concerned about its impact on the boys’ teams.

“Men were a little worried that money was going to be taken out of the men’s program to help the women’s program, but that wasn’t the intent of Title IX at all,” Slack said. “It was to give women equal opportunity and equal services. It didn’t take away from any of the men’s programs, it just helped the women’s program so much.”

Once Title IX passed, Slack noticed her requests were taken more seriously.

“My requests were not elaborate because I knew I was going to have to fight for it, but after Title IX, if they were spending thousands on one boys’ team, they had to spend the same on the girls’ team,” Slack said. “It meant so much to us as coaches, because all of a sudden I had a right to ask for things, rather than wait to be granted something, like a gift or a favor. Before Title IX, for example, if I asked for four dozen field hockey balls, I might have gotten one dozen at best.”

After Title IX was passed, girls’ interests in participating in sports increased, leading to more teams being created.

“After Title IX was passed, some girls wanted to run track or cross country, and they included them on the boys’ team,” Slack said. “Eventually, after enough girls joined the boys’ team, they would make a girls’ team. Because legally no one could say no, they had to provide it if there was enough interest.”

Gradual Changes

However, oftentimes it took a while before a new girls’ team was formed at Algonquin, according to former Athletic Director Dick Walsh. Walsh was the AD when Title IX was passed.

“It wasn’t super quick to make a new girls’ sports team because a lot of the other schools did not have those girls’ sports yet,” Walsh said. “You can’t really have a team without opponents or a league; there had to be teams to play.”

In addition to affecting conditions on the field, Title IX changed dynamics inside classes as well.

“Before Title IX, boys and girls were never on the same side of the gym; that was not even thought about,” Walsh said. “After Title IX was passed, the gym classes were not separated anymore and girls and boys did the same activities.”

Serafin worked at NBC covering golf tournaments, but did not notice a significant difference in the workplace immediately after Title IX was passed.

“I did not really see an impact in the first couple of years since it had passed, money was certainly not raining down,” Serafin said.

Although Serafin didn’t see an impact in the first couple of years since Title IX passed, Slack believes its impact has strengthened and can be seen today.

“It certainly helped bring schools that were not up to standard to improve a lot,” Slack said. “As far as the schools are now, if they can’t comply, then parents and educators have a right to make them comply as far as making opportunities available for women.”

Lasting Impact of Sports

Title IX has enabled girls’ sports to impact many lives, as they mean more than exercise and winning; they build friendships and teach valuable life lessons.

“Being on a team, you learn compassion from each other and to support one another, and certainly can learn a lot from adversity,” Slack said. “You can either keep fighting or stop and that’s what you learn; you have to continue on, which is a terrific life lesson.”

Serafin agrees that playing sports was a valuable portion of the high school experience.

“I grew up in a house where the driveway was a basketball court and the backyard was the baseball and football field; there were sports being played at my house all the time,” Serafin said. “It gave me pride to be a part of a sports team, a team that represented our school.”

The teams created as a result of Title IX have built lifelong relationships, as McGowan stays in touch with her old teammates.

“I still meet regularly with friends from field hockey,” McGowan said. “We get together once a year; the friendships that you make will last you a lifetime.”

Some things haven’t changed.

“The bus rides to and from games were one of the best parts of playing a sport,” McGowan said. “I was proud of being a decent player, for going out, working hard to get on the team, being a part of the team, and I have so many fond memories of doing it.”

Sports continue to impact the lives of many of these women, over 50 years later.

“I still play golf in a women’s golf league, but I’m also still involved in sports through my children and grandchildren,” Cooley said.

Although Serafin doesn’t currently play a sport, she is still active and supports her grandchildren in their sports teams.

“I enjoy water skiing, and when I was almost in my 50s I played co-ed softball,” Serafin said. “Now, I get to watch my granddaughter play flag football.”

Access to women’s sports has also increased through television.

“I love to watch women’s sports, especially tennis and soccer,” McGowan said. “Back then, they did not televise women’s sports like they do now.”

Cooley was the first female Little League coach and Serafin was the first women’s coach for basketball in Northborough.

“I coached those boys when they were 5-6 years old to Babe Ruth,” Cooley said. “It is very rewarding to see the same boys hang out together and call me Mrs. C; you can’t even imagine how rewarding that would be, these are the community sports we didn’t have.”

Today and the Future

In the 2020-2021 school year, ARHS had 596 male and 541 female student athletes, and in 2021-2022, there were 629 boys and 541 girls participating in sports.

“As you can see from the data, the impacts of many years of progress are considerable,” Mocerino said. “For example, our women’s ice hockey team won the program’s first-ever state title. The girls’ ice hockey team’s gritty, gutsy, joyful win was the culmination of a magical tournament run and of 50 years of progress for ARHS.”

However, while Title IX has made a large impact on athletics, there is still more progress to be made.

“I was excited about it, and I wanted everything to be equal,” Cooley said. “But I’m aware that it wasn’t a sudden change and it still needs to improve. Look at how long it’s been since the bill was passed; as far as I’m concerned, it’s not where it should be, but it’s definitely an immense improvement over not having it at all.”

Walsh agrees that the progress took time, and that there is still more room for improvement.

“I think the girls should be credited more than anyone else with the fact that they kept pushing and pushing; it took a long time and it wasn’t done overnight either.” Walsh said. “Now, I think the girls are fairly even; I don’t think they are fully even yet, but they are getting there.”

This story was originally published on The Harbinger on December 8, 2022.