Inside the mind of mental health treatment

February 2, 2023

Imagine spending all day in bed. Blissful, right? Now imagine that bed in an isolation chamber, under the watchful eye of a nurse.

This is the reality for some students suffering from mental illness across the country.

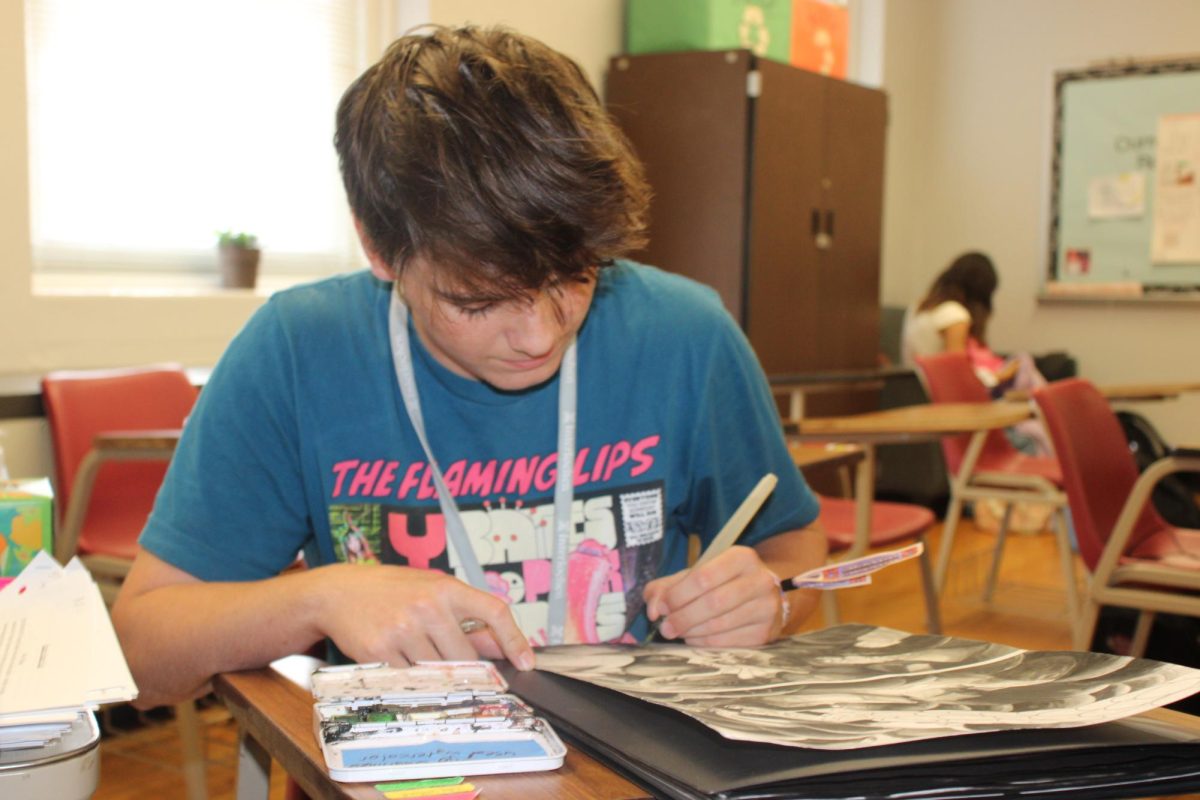

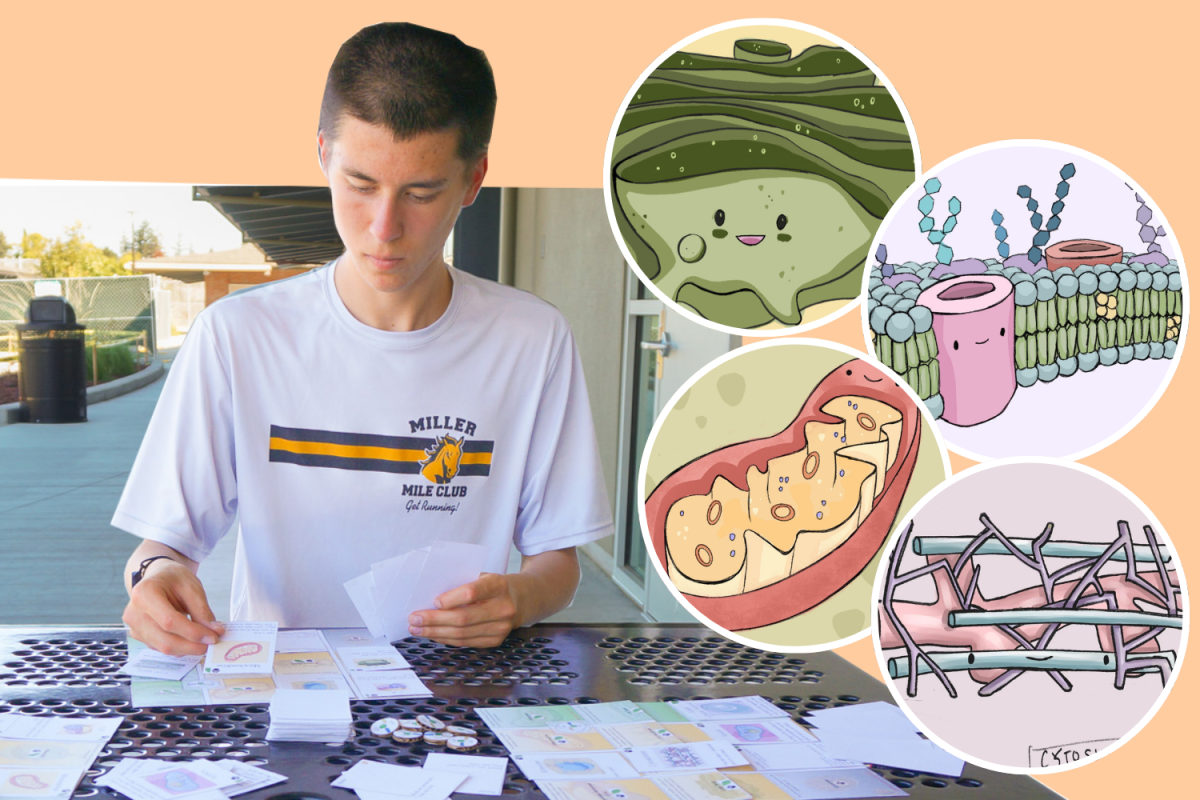

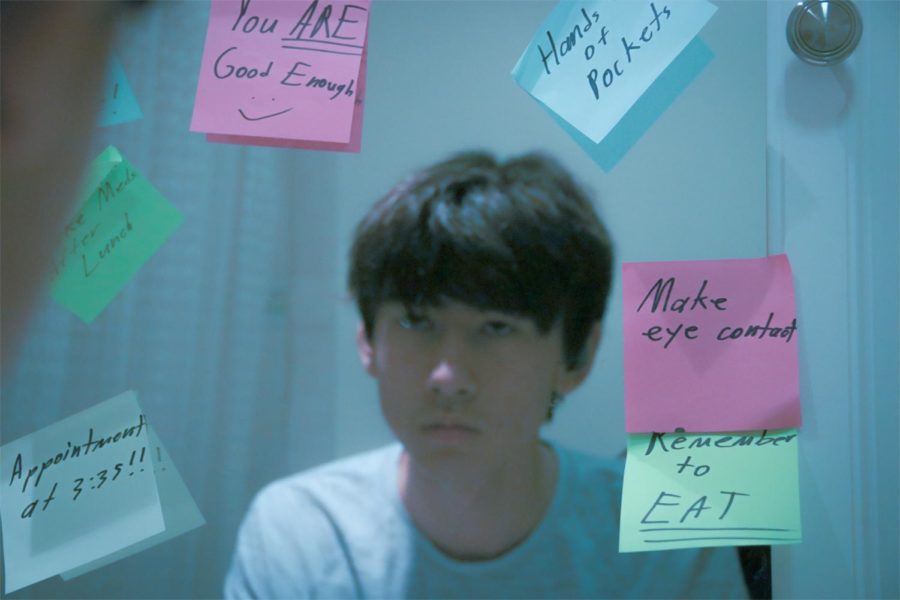

Rei Cheung

Rei Cheung, a junior at Carlmont High School, is one of these students. To Cheung, spending time with friends means everything. He enjoys shopping for clothes with his friends and plans to be a fashion designer. He also indulges in anime and video games to unwind from the daily drone of life.

His journey began when he visited his pediatrician to seek therapy for his eating disorder under his mother’s recommendation. After talking to his pediatrician, Cheung learned that it would take two months to speak to a therapist. After anxiously waiting, he finally obtained a session with a therapist.

“We couldn’t even get started on what I wanted. We would need three or four other visits, which would be around two weeks in between, and we had to go to a hospital,” Cheung said.

One day, Cheung visited his pediatrician for a checkup. To his surprise, the doctor said that he needed to transfer to a hospital after observing his low heart rate and low blood pressure caused by a hybrid of stress and fasting. Cheung went home to eat dinner before being sent off in the early morning to be admitted to a hospital.

“I did not know that I was gonna go to the hospital before that visit, and then she was like, yeah, just have dinner at home, and then we’re gonna ship you off,” Cheung said.

Upon arriving at the hospital, he was given a bed. Later he found out that there was a waiting list for beds, which made Cheung feel grateful knowing he got treatment sooner than most patients.

“I think I was really lucky. But for all those people who missed their opportunity and had to wait, I think that’s really messed up,” Cheung said.

Life in the hospital for Cheung was miserable. He was not allowed to leave the bed at any time unless it was to use the bathroom or shower and was monitored at all times. During his stay, he had gotten food poisoning from the food provided to assist him with his eating disorder.

“It’s really ironic, I really think that they should have higher safety measures. I know that they may not have the budget for this, but maybe you should think about what you’re treating,” Cheung said.

Drained by the ordeal, his psychiatrist prescribed him Zoloft and four other medications, including Prozac. Cheung was cautious of the idea of taking medication and was worried about withdrawal symptoms.

“I hate it whenever they prescribe something new to you; you have to wean yourself off one and go back on to another one,” Cheung said. “It’s the most mind-boggling, head-aching process ever.”

Cheung’s most significant concern was for patients who are suffering from conditions similar to his, such as anxiety or bipolar disorder and are unable to get necessary treatment due to long wait times for admission. He especially felt sympathy for those in critical conditions similar to his.

“Some people could just be really unstable and are unable to continue living the way they want to, or they could harm other people or themselves. They could start taking drugs to not think about it. I just feel like if people got help at the right time, things would be a lot easier for people. Maybe they wouldn’t go looking for something else to fill that void,” Cheung said.

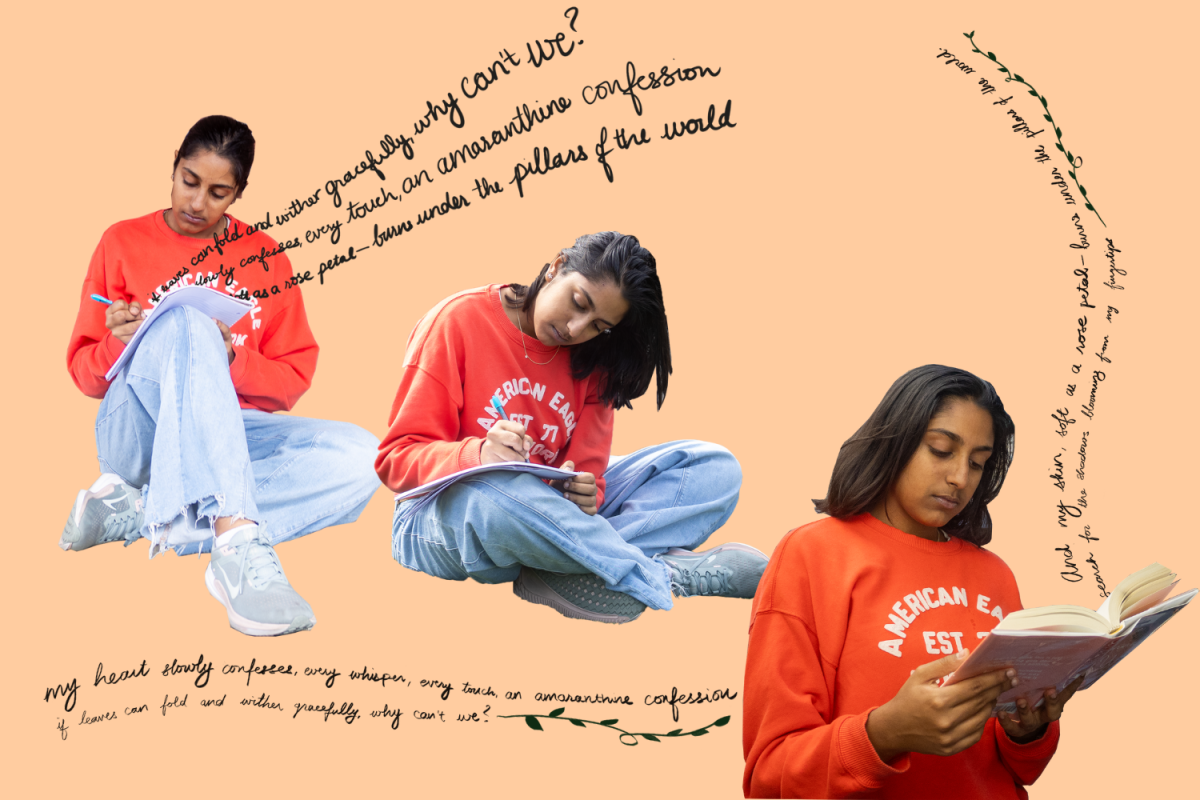

Leah Randhawa

Leah Randhawa, a sophomore at Tide Academy in Menlo Park, California, is another student who spent her days in a mental hospital. She has suffered from suicidal thoughts and an eating disorder. Like other high school students, Randhawa spends most of her time with friends. She’s on Tide’s rowing team and is passionate about getting high academic marks to attend the University of California, Berkeley, to pursue a career in computer science.

Her treatment experience first began when she started visiting her pediatrician due to her suffering from an eating disorder. As a wellness checkup, Randhawa filled out a form that expressed her feelings in which she remarked about having suicidal thoughts. This continued for four years of visits until Randhawa noticed the flashes of an ambulance outside her home one night out of the blue. First responders were called for a possible mental health crisis, and Randhawa’s home was deemed an environment too harmful for her. She was taken to the emergency room that night.

“They took the only words ‘I want to kill myself’ as a way to send people to the ER, but when you kind of word it in a different way, like ‘oh, I’ve just not been feeling well,’ you’re ignored,” Randhawa said.

For the 26 hours, she was in the emergency room on a waiting list for transfer to a psychological ward, she was contained and monitored by a security guard within what she described as a “glass room.”

“Your room is completely empty and the only thing you have is a cell phone and your parent for the whole 26 hours,” Randhawa said.

After the ordeal, she was transferred to a psychological ward for three days, during which her psychiatrist gave her low doses of Prozac. According to Mind, a non-profit organization raising awareness of mental illness, Prozac is a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant that is also known as fluoxetine. It works by blocking nerve cells in the brain to extend the effect of serotonin.

She also remarked that seeing figures walking across her room gives her immense anxiety at the thought that one of these “shadows” might attack her. These hallucinations would stay with her even after she visits the psych ward.

“I was insanely paranoid all the time. I’d never leave my room when people were in the house because I’d think that they were outside my room when I’m sleeping. I would never move from a specific position because I feel like they noticed me, and I’d get really freaked out,” Randhawa said.

Now having medication and a medical professional guiding her, her psychiatrist recommended her an Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) with her parents, a form of group therapy. Randhawa mentions that she was incredibly uncomfortable with the process, as she never opened up to her parents at the level the doctors were asking. This continued at 11 hours a week for two months.

“You literally just get couples therapy with your parents, and it’s horribly awkward because I don’t talk to my parents,” Randhawa said.

Randhawa stresses the disconnection between teenagers who have mental illnesses and the adults trying to help them. With her sudden admission into the mental health system, she feels the ordeal worsened her feelings of depression and anxiety.

“I’m doing perfectly fine. A lot of things with therapy is that they try to provoke past memories, and those are the things you don’t want to remember because you’re trying to move on,” Randhawa said.

A hard pill to swallow

The individual stories of both Rei Cheung and Leah Randhawa reveal two common flaws. One is the mental health system’s inability to treat patients early in their illness, and the other is the emotional disconnection between the patient and the medical professional.

According to a 2022 report by Mental Health America (MHA), over 60% of United States youth (aged 12-17) with major depression did not receive any mental health treatment. Even in a state with the greatest access, nearly one in three are going without treatment.

“It’s almost a human rights concern, in some sense, we do have a youth mental health crisis in our country, and I’ve seen in the last two years post-pandemic, that things have gotten acutely worse and harder for young people,” said Jules Villanueva-Castaño, a mental health crisis first responder.

Castaño, a mental health first responder for fifteen years and advisor for the juvenile justice system, has seen first-hand the effects of late-stage-mental illness. Due to the nature of his occupation, he understands that speed is critical for those suffering from severe depression or suicidal urges.

“It feels very frustrating to hear that there are waitlists, that there continue to be waitlists for young people to receive crisis-level psychiatric services,” Castaño said.

According to Castaño, given the complex nature of mental illness, it is difficult to connect with patients given factors such as stigma, fear of being judged, or having no outlet to voice their feelings. The important takeaway is the encouragement of youth to seek help earlier in their illness.

“I think that adults need to listen more, and adults in the system need to pay attention. We need to be bringing to bear more resources, and really asking questions that maybe adults don’t really traditionally want to hear the answer to,” Castaño said.

To Castaño, though mental health treatment has many holes and gaps, it is vital for a healthy and happy community, and he believes that every good system comes with change.

“While I am critical of the system, I also know that it’s necessary and needed for young people,” Castaño said.

The future of mental health treatment

Mental health is necessary for the health and happiness of all communities. However, it needs reformation and tangible solutions to make the treatment experience more accessible and positive. Fortunately, these solutions are in the works.

In an interview with Dr. Steven Sust, a psychiatrist at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health, he mentioned that, like with any medical illness, it is best to treat the condition as early as possible. This would give psychiatrists and other doctors more time to spend on patients without risking worsening their condition.

“We are getting better and better and identifying and treating mental illness as they occur, especially if we figure it out earlier,” Sust said.

Sust also mentions that there aren’t enough psychiatrists and mental health crisis responders that meet the number of patients seeking help. This results in the waitlist causing many patients’ conditions to worsen. With more qualified medical professionals, hospitals would be able to keep up with the demand for treatment.

“Truth of the matter is that there’s just not enough people like myself, people like my colleagues, out there, especially in crisis moments. That’s why it is so important for our patients to come to us early to compensate for the shortage,” Sust said.

Along with the changes to the mental health system itself, Sust, along with his team, including Castaño formed a non-profit Stanford initiative project called Allcove. It is a mental health center for the youth based on the integrated health system in other countries like France and Ireland. These centers provide specialist counseling, peer support, and education and financial guidance. Along with all these benefits, it is free of charge, and services are open to anyone between the ages of 12-25.

“It’s not up to one person to decide what to do; it’s very much all of us as a community to decide how much we would like to continue, and encourage others and not let them give into stigma and such,” Sust said.

Although the mental health system has flaws, it is actively being improved. Along with the model of mental health, treatment is being reshaped into something much more accessible for anyone seeking mental treatment. The future of mental health looks bright on the horizon.

“Everyone here in the community, your teachers, parents, pediatricians, and therapists, want to help you guys. Though we aren’t exactly perfect, my hope is that we can all work together to help you reach whatever rockstar or superhero dreams you have,” Sust said.

This story was originally published on Scot Scoop News on January 25, 2023.