Ashlyn Gillespie

Historically, photography has long been biased toward lighter skin tones. Over the years and over many different photography companies, students like junior Elizabeth Franklin have begun to see this bias seep into their school pictures. “It’s disappointing that each year, my school photos looked wildly different. Some have glares, and some are completely oversaturated,” Franklin said. “They don’t look like me and they don’t really represent me.”

Photography through a racial lens

A photographer peers through their viewfinder. The subject smiles. A camera flashes. Every photo captures a moment in time. But for many people of color, pictures rarely capture authentic skin tones.

Whitewashing in photography is a long-standing issue, stretching back to the beginning of film photography when Kodak was the premiere camera company. Film cameras work by exposing sensitive chemicals in the film to light, capturing an impression of an image. However, the chemicals Kodak used in their film were only tested on and optimized to capture paler skin.

Additionally, Kodak was responsible for printing the film reels that photographers brought to their stores. Once exposed to light, film is developed in a chemical solution, turning the impressions into colored images. The formulations of the chemicals determined the intensity of their colors. Kodak stores used Shirley cards — photos of pale, white models — as the standard to check and calibrate these chemical solutions. Yellowish, reddish and brown skin tones were ignored. This meant that when a photographer went to print their photo reels, they would only be correctly optimized for lighter skin tones.

Thus — as usual — white became the norm. This issue sparked concerns from Black parents after Brown v. Board of Education required schools to integrate, and African American children were captured in photos alongside their white classmates. While Kodak cameras accurately captured white students, photos of Black students blurred their facial features. For years, protests from Black parents were ignored. Kodak only fixed film formulations when furniture and chocolate companies complained that they could not capture their products’ dark tones and specific details. Finally, to please these companies, Kodak created multiracial Shirley cards and formulated new film with different chemicals to capture details on darker skin and subjects.

The development of digital photography created new issues that continue to hamper the authentic portrayal of people of color. Digital cameras operate using sensors made from millions of pixels arranged in a grid that absorb light to generate images. However, these pixels are not optimized to capture darker skin tones. Exposure systems built into modern digital cameras were also largely designed for lighter skin tones. This means when multiracial groups are photographed, many camera algorithms — including those used in some phones — leave darker skin tones looking darker, oversaturated or blurry.

Along with hurting individual clients, bias in photography can impact the overall quality of representation afforded to people of color in popular culture. For example, when Simone Biles was featured on the cover of Vogue, many readers noticed the poor lighting that made her look muted and washed out. Even in professional photography designed to feature on the cover of a national magazine, photographers neglected to capture Biles’ true skin tone.

For many students, seeing people of color misrepresented through photography is disheartening. However, the effects also bleed into students’ daily lives.

In School

One day every school year, students dress in their best clothes and meticulously comb their hair, buzzing with anticipation. That day is picture day. Inevitably, when school portraits return a few weeks later, some students are satisfied, while others are disappointed.

While occasional unflattering photos may be inevitable, some students of color have found that their skin tone has looked inaccurate or improperly exposed in their photos. These photos are put in the yearbook for everyone to see and look back on.

“I always end up looking either darker or lighter than I am in real life. It’s sad to see because there are so many other kids who have my skin tone or experience a similar issue to mine, where nobody knows how to light our skin correctly,” junior Elizabeth Franklin said. “It’s frustrating because, in one of my school pictures from second grade, I might be this color, but in my eighth-grade picture, I might be several shades darker. My parents put up my pictures at home, and I would like them to have an accurate representation of who I am.”

Junior Rithanya Sivabalan also notices that her school photos often portray her skin tone as darker than reality.

“The school picture goes in the yearbook [and] I feel like it’s not an accurate depiction of me. I don’t feel as equally represented [as other students],” Sivabalan said.

Furthermore, some students of color have noticed glares in their photos from improper lighting. Harsher lighting can cause students of color to have glares in their photos, whereas white students wouldn’t have that issue.

“[Photo companies] don’t know how to light melanated skin. Sometimes a glare is shown on my forehead, it’s very prominent, and I do not like it because it takes up half of my forehead,” Franklin said.

Different photographers and photo companies also play a role in whether skin tone is accurately shown.

“I had a really good picture last year [from Wagner Portrait Group]. There was no glare. There was an accurate depiction of my real skin tone,” Franklin said.

While not all students of color have noticed these discrepancies from reality, accurate representation of students’ skin tones remains an important goal for many. This includes co-owner of Wagner Portrait Group Penny Wagner — the portrait company that partners with and donates to Parkway Schools. Wagner aims to create quality photos.

“The Wagner Portrait Group’s mission is to provide a superior image with an exceptional experience, dedicated to the unique needs of our customers and their entire community,” Wagner said. “We want everyone to know that we offer special services to your schools and families. We continue to educate ourselves with the ever-changing technology to pass that expertise on to the schools.”

Although it is continuously changing and improving, photographic technology still has many biases built in. However, by paying more attention to lighting and editing, professional photographers can capture accurate, representative photos of people of color.

Solutions

Despite biases built into photography, darker skin tones are not necessarily harder to photograph. Lighting is one key facet in capturing true skin tones. St. Louis-based artist Colin Eliot — whose photography has been nationally recognized — believes that placing time and care into photography can make subjects appear more true to their authentic selves, no matter the skin tone.

“It’s a mixture of being present as you’re making the photographs and really paying attention to how light falls on different skin tones,” Eliot said. “So for instance, you don’t want to place too much light on somebody’s skin tone, because it may not be accurate to what their complexion is. Whereas, on the opposite end, you don’t want to add too many shadows to someone’s skin because it may make them fall into the background of the image.”

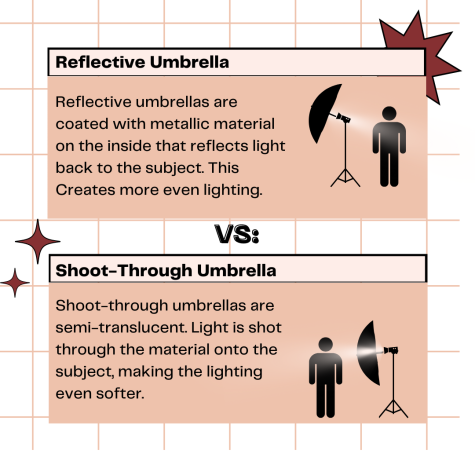

Experts recommend using softer, reflective light when photographing darker skin tones. Typically, school photographers have two light sources. One light is pointed at a reflective white umbrella, which then directs the light onto a metallic reflector that illuminates the subject’s face. The other light has a soft diffuser that evens light and aims to create more separation between the subject and their background. While this achieves more diffused lighting than if a direct light source was pointed at the subjects, many students of color still see prominent glares and shadows in school photos. Furthermore, because our school photos are usually taken in the gym — which utilizes harsh fluorescent lighting — darker skin can become inaccurately exposed.

One simple solution would be to move the photos to somewhere where harsh lighting does not interfere with quality. One possible location, weather permitting, would simply be outside. While natural light can be hard to control, portrait photographers like English teacher Erin Fluchel believe it can better portray true skin tones.

“I exclusively shoot natural light. It’s more beautiful. It makes people’s skin tones look like them. It’s harder to control, certainly, but I can see a difference if I don’t use natural light. I’ll see things that have a blue tone or don’t look like people’s natural skin. No matter who I’m photographing, I try to make sure that they are well-lit,” Fluchel said.

Thus, using sunlight could eliminate the issue of harsh lighting in the gym. But even if the photographs take place in lieu of natural light, an indoor location with softer lighting would improve the quality of student pictures.

Click to see pictures of junior Samari Sanders taken in different lightings. If on mobile, view in landscape mode.

The logistics of utilizing natural light can be more complicated to organize, especially around weather issues, since overcast or shadowy areas can lead to further inaccuracies in lighting darker skin. However, by adjusting exposure, quality images can still be captured.

“If we [are] in an outside environment photographing an event such as sports or graduation, the exposure could change throughout the entire assignment. Again, metering for correct exposure is key to a great image, so photographers will stop and do this continuously,” Wagner said.

Furthermore, different tools could be used to suit students’ specific skin tones better. For students of color, using a diffusing umbrella — which creates a softer light by passing the light source through a white fabric before it reaches the subject — instead of a reflective umbrella could help further. While harsher light creates more defined highlights and shadows, softer light can reveal more complexity and range in skin tones, which can better suit darker skin that absorbs more light. Because different lighting and backgrounds suit paler and darker skin differently, these settings would have to be adjusted for each individual getting their portrait taken. Many photography umbrellas available can be easily converted from reflective to diffusing, depending on what better suits the subject. This could add another tool to a photographer’s repertoire for accurately capturing skin tone.

However, though technical and practical solutions can be suggested, the most important factor in more inclusive photography is taking the time to make sure that photos look accurate to students’ true skin tone. While the nature of school portrait photography means quickly photographing many students, school photographers must take the time to optimize lighting for their subjects to accurately capture students’ skin tones. While taking a lot of photos quickly is often required of school photographers to optimize efficiency, those who inaccurately represent students’ skin tones do a disservice to their clients.

Wagner believes it is important to calibrate cameras to accurately capture skin tones in the beginning stages of the photography process.

“As opposed to ‘correcting’ skin tones after photography, it is of vital importance for professional photographers to check and meter the exposure of their camera and lighting prior to photographing pictures. This is the key to a great image and accurate skin tones,” Wagner said.

In post-production, new advancements have improved Wagner’s process for editing school photos.

“When the images come back to the Wagner office, each [photo] is checked for exposure and quality of the image before being printed. Years ago, when we photographed with film, we didn’t have the flexibility to color-correct an image. If an overall image was too dark, it was very difficult to make it lighter,” Wagner said. “With digital correctors, it takes seasoned professionals to make color-corrections to uphold the integrity of skin tones and the environment in which the subject was photographed. Within our labs, there are whole teams that study color correcting software to be sure any adjustments are consistent and true to life.”

But even with these advancements, it can be difficult for editors to know what a subject’s true skin tone looks like when the subject is not standing in front of them. Many photo companies allow parents to adjust and pick a background for their students’ photos through the parent portal. A similar method could be used during the editing process, where parents or students could have more input on adjustments made to a photo to ensure that their skin tones are true to life before these photos are used in yearbooks or school IDs.

While editors often have to adjust a large mass of student photos, ensuring skin tones are well-lit and not overexposed in post-production can make a huge difference. Each student has different undertones and shades in their skin. Photographers can make sure each student looks their best by taking the time to individualize editing instead of using generic presets for each photo. While this would take time and perhaps cost more for photography companies, it would ensure that the editing process for school photos is fully inclusive for every skin tone and makes each student look their best.

“No matter who I’m photographing, when I edit, I try to make them look like the best versions of themselves. I’ll change a pimple or a scab, something that’s not a permanent fixture on their face. But if it’s a birthmark or a skin tone, I leave that part of them, [which is] part of what makes them unique,” Fluchel said. “A good photographer will try to capture the best version of [their subject] and keep those tones true to nature.”

Photography and editing are difficult processes, but revamping the production process for portraits of students of color would reaffirm photographers’ commitment to both quality and — more importantly — equality.

Whether or not your school picture is hung on your fridge for eternity or relegated to your school ID and yearbook, photography companies must adapt to photographing melanized skin. By failing to truly capture students’ skin color, we disrespect and misrepresent an important part of their lives.

Every photo tells a story, and our school’s story should show the diversity and inclusivity of our student body.

This story was originally published on Pathfinder on February 23, 2023.