There comes a time every year when stores and games and rides bloom out of the ground, all encapsulated in a little bubble of fantasy and escapism. As summer turns to autumn and the leaves begin to fall from the trees, the magical realm of the Texas Renaissance Festival opens its gates.

I’ve attended annually since before I can remember, and I have almost everything that stays constant about the place memorized. The grass is always yellow and crunchy, the air always smells of incense and gourmet pipes. The “guards” who scan your tickets at the entrance always have fake kiss marks on their cheeks, and the jester always stands just beyond the gateway, ready to hand faire-goers a timetable. The arena always stands tall in the middle of the faire grounds, and joust matches are always held at hourly intervals. I always walk in with someone, ready to get lost in a world of fantasy and inaccurate history, and up until my freshman year, that “someone” was always my father.

My father is as left-brained as one can come. He specializes in accounting, numbers are his language. He’s an immigrant who sticks to the statistics and hates owning anything impractical. In many ways, I find myself to be his opposite; I pride myself on my creativity, my way with words. My love of the deeper truths which can be found in fairy tales and cartoons. However, my father isn’t as one-dimensional as he seems at first glance. He loves astrology, and believes in the magic of the stars in a way I never will. He loves American movies, the opera, his children—but most importantly, he loves the Renaissance Fest. I do too.

Cancer isn’t an interesting story anymore. Everybody’s heard it, and I’m not sure anybody cares to listen again.

When my father received the news of his ailment, he hadn’t lived with me for a while. He had already moved to Dallas during my freshman year, then Oklahoma when I was a sophomore, following after my step-mom’s job opportunities. By the time he informed me that the doctors had found cancer in his body and that it had already spread, I only saw him during his monthly visits.

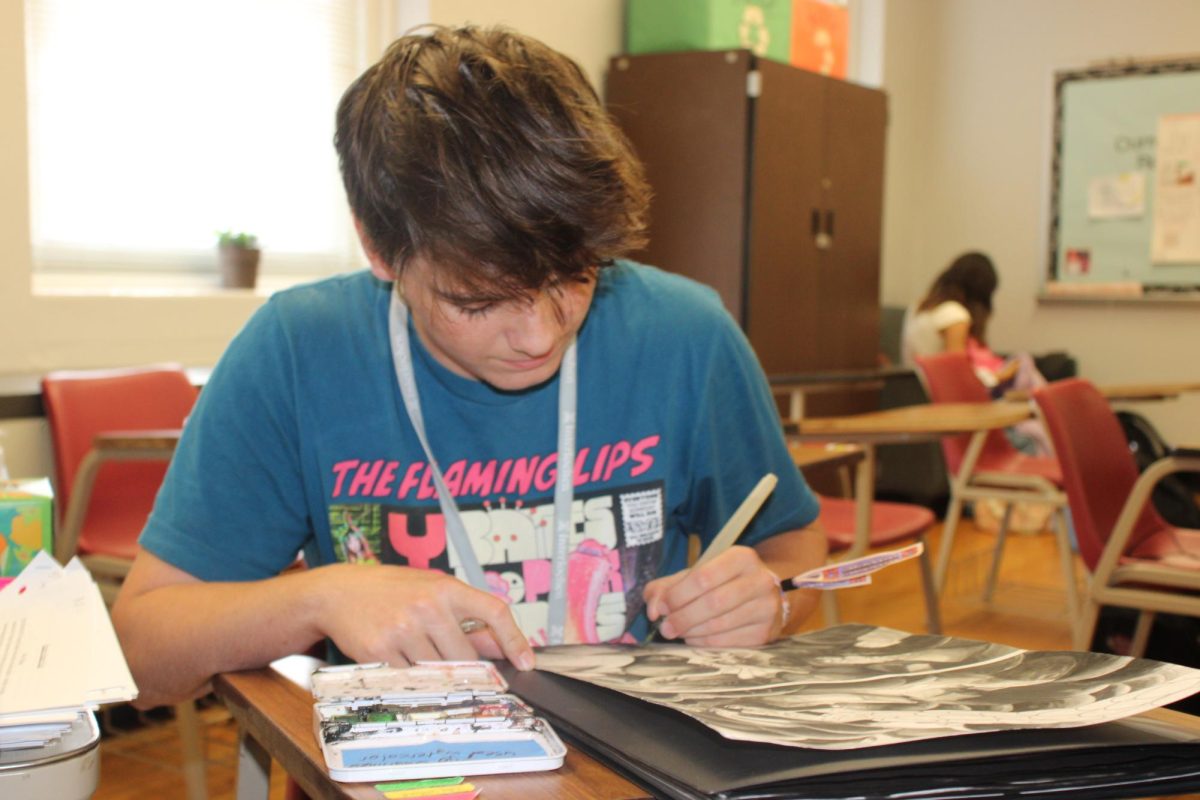

The king had fallen ill. It didn’t really feel real. I continued on with business as usual, creating lighting fixtures for my school’s theatre department, copy-editing news articles for its publication.

In Tangled, the best 3D animated Disney movie of all time, when Rapunzel’s mother falls ill, she drinks from the broth of a magic flower and is healed immediately. The faire had a lot of flowers that resembled the golden bloom, but none had the ability to heal my father.

In the beginning, my elder sister used to call or message me with statistics of how likely dad was to survive what he was going through, what his life expectancy was.

7 years.

That’s the number that stuck. Most people with his disease at its severity lasted seven years longer after diagnosis, according to some random article my pre-med-track sister dug up.

15 years.

That’s how many consecutive years I had attended the Renaissance Festival, over double the amount of time the internet predicted my father to live. He had already taken a leave of absence from his job at least a month or two after he told us, as he wanted to spend more time with my baby half-brothers. The little princes.

It wasn’t until I stepped past the gateway of the Renaissance Fest in the Autumn of my junior year that I truly felt his mortality. He hadn’t visited in a while, and when he did, it wasn’t for long enough to attend the festival, so I went with my friends. I dressed up like a faerie and I went about all day feeling like someone had stolen all my pixie dust. It all felt weirdly hollow, like something was missing—but not in the way something feels missing when you can’t remember what your last homework assignment was. It felt more like a puzzle with a piece that’s nowhere to be found, like I knew exactly what I needed but it just wasn’t there. At some point, I sent him a selfie of my friends and I, and he sent back a message about how much he missed the festival. I started crying.

Renaissance festivals are not historically accurate in any regard. But most are at least loosely based on 14th-17th century Europe. That’s over 400 years, just as a loose estimate. You may think you can conceptualize how much the world changes in 400 years, but I promise you, you can’t. Within 400 years, empires are built and slain in the same breath, hundreds of kings or chiefs or whatevers come in and out of power all around the world. The attitudes of people change too many times for even historians to pinpoint all the differences. When you’re living it, a year feels like a century, yet a century is still a century.

Over the course of just a year, my father’s health declined considerably. When he was first diagnosed, he couldn’t even detect anything wrong with himself. It was the medications and the stress and the chemo that turned his hair gray and wrinkled his skin. This was aging I expected over a decade, yet that year truly felt like it had ten fit into it. He looked the way I expected him to when I had grandkids.

Or maybe he had been aging the whole time, and I only noticed when I had to.

I occupied myself with theatre, school work, clubs, the ever-impending doom that was college apps. I visited the Renaissance Fest that year more times than I ever had before, possibly three to four trips. Despite my dad not accompanying me to any of those, he did begin to visit more frequently, at least once a month. Rather than receiving all my updates over text, I began to receive them from his mouth.

When he first told me, his acceptance startled me. His immediate plans for a future where his presence wasn’t guaranteed were made from the very first meeting. It wasn’t an indifference toward what might happen to him, it was just a weird and eerie air of resolution. As if he already expected a, “The end.”

His fight seemed to kick in later. Suddenly he was scheduling an appointment with any type of doctor who could help, searching for the magic flower. This was when he began all these things that functioned to age him in order to paradoxically lengthen his life.

Yet, the treatments worked.

His cancer wasn’t healed, what he has can’t be, but he was better, it had abstained, the statistics had lengthened. He began to lose the worst of the effects of his treatments, though some things still linger, like how a paper that is crumpled still maintains its wrinkles even after being flattened. His recovery wasn’t dramatic nor was his decline, and sometimes I feel bad about getting so hung up over something ultimately anticlimactic.

In most fictional genres, though numerous popular fantasy tales are especially guilty of it, there are many identified devices and tropes that basically dumb down to, “The problem is fixed, but not because of anything the main characters did.”

Dues Ex Machina, the chosen one, etc. You know the drill. As a viewer or reader, they suck. They’re frustrating, unfulfilling, they make it feel like the whole story happened for nothing. When you’re living through it, they’re anything but. In reality, I know I’m not the protagonist of my father’s story, yet when you live life in your own body, see through a personal lens, it’s okay to be a bit selfish. That doesn’t change how I wasn’t able to do anything, though.

I couldn’t attend his appointments, remind him to take his medications, search the entire world for a magic flower that could heal with one sip of its broth.

At the Renaissance Fest, everyone is the protagonist of their own fantasy story. Everyone is the mysterious traveler searching through a merchant’s wares, or the bubbly fairy interacting with the kind people around them, or the swashbuckling rogue winking at barmaids. Even if you don’t have the best costume, or any at all, you can still create your own story. You have control. However, others do too, and that spontaneity is what makes it so fun.

For a long time, I was the youngest princess visiting with their fellow monarchal relatives. Or the youngest bear of the three. Whoever I was, it was a part of something, and he was a part of it, too.

That can still be true, in or out of the fairgrounds. Even if I can’t control every facet of my life, it’s still mine. Sometimes events unfold outside of my control and all I can do is offer love or advice or a listening ear and that’s fine, because there are things I do have control over and can change.

I may never be able to change my father’s health with a single snap. I can’t protect those I love from the everyday obstacles of life. I can’t even protect myself from the unpredictable, but that doesn’t matter. I know what I can change. My love, where I place it, where I choose to devote my time and energy. I can’t stop my dad’s cancer, control its ups and downs, but I can make sure he feels supported throughout its tenure.

Despite her Jewish heritage, my mother always loved the serenity prayer. She jokes that it’s something Christians got right, and even though I’m barely religious, I’m inclined to agree.

It goes:

“God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to know the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.”

The message rings true, whether God is granting it or not.

This story was originally published on Upstream News on February 17, 2023.