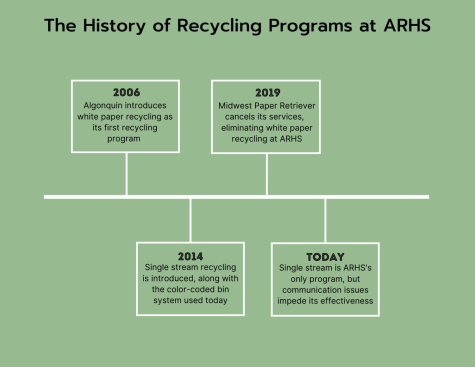

Since its origin in 2006 with the introduction of white paper recycling, Algonquin’s recycling programs have undergone numerous changes due to new initiatives and decreased participation rates. Presently, ARHS uses the single stream recycling program, and both students and staff recognize a need for change to make the program more effective.

The single stream program is a system where all recyclable materials, including white paper, don’t have to be sorted and are collected together by the company E.L. Harvey and sorted at their facility.

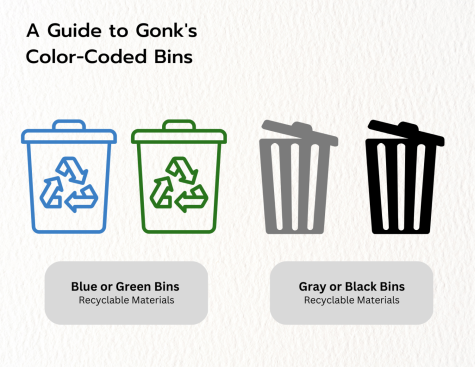

Currently, Algonquin uses a colored-bin system in each of the classrooms to denote which bins go to recycling and which bins go to trash. According to facilities director Mike Gorman, black and gray bins are for trash and green and blue bins are for recycling. Recycling bins should be accompanied by signs describing what can and cannot be placed into single-stream bins. According to a Harbinger audit in early March of 55 randomly selected classrooms from all hallways, signage was inconsistent from classroom to classroom, and 40% of classrooms had an incorrect number of bins (either too few or too many trash and/or recycling bins), which could lead to confusion for students and teachers.

Materials that are properly recycled must not be contaminated by non-recyclable materials, which poses challenges particularly in a school environment. If custodians see any food in either a green or blue recycling bin, the entire bin is considered contaminated and thrown out with the trash.

“[The custodians] used to try hand pick it when [the amount we were recycling] first started dwindling, but it got to be so much labor and it was ridiculous and no one is even paying attention, but that’s where the students can step in, the teachers can step in,” Gorman said. “We are still recycling if [people dispose of their waste] properly.”

Twice a week, facilities sends out a 20-yard container of recyclable materials to E.L. Harvey; however, according to Gorman, this is significantly less than the 45-yard containers ARHS was once exporting in the same time frame. The switch from the 45-yard containers to 20-yard containers occurred in 2018. Recyclables are collected from green and blue recycling bins by janitorial staff and deposited into these containers.

Due to the lack of buyers for recycled materials in Massachusetts, a sizable portion of Algonquin’s recyclables is sent by E.L. Harvey to a local power plant in Millbury called Wheelabrator, where they are incinerated to generate electricity which we buy back at the standard rate.

“It’s getting harder and harder to find a place in Massachusetts to take the recyclables…Our trash does go and it does get turned into electricity and we do buy off the grid,” Gorman said. “It’s kind of a round-a-bout way of recycling.”

Confusion & Frustration

Although the colored bins are meant to encourage recycling within the school, some students and staff members believe that there is a lack of effective communication about the bins.

Senior co-president of the Green Earth Club Lee Gould expresses a need for better communication about the color-coded recycling bins.

“I think definitely we can specify which bins are for recycling and which ones are for trash,” Gould said. “Having students understand fully what materials can be recycled, more than just a little poster because no one really looks at that.”

According to a Harbinger survey of 160 students conducted via Google Forms from Dec. 12 through 15, 53% of respondents said they could sometimes differentiate between recycling and trash bins and 32% of respondents reported they are never able to differentiate between the two bins.

Gorman believes that student involvement in recycling programs is essential to the success of the single stream process.

“It’s really up to the student body to get involved,” Gorman said. “The reason why the system has failed is because the student body lost interest. It takes a whole village and it has to be driven by the students.”

According to the Harbinger survey, 73% of respondents reported that they always recycle at home, while only 15% of respondents reported that they always recycle at Algonquin. Part of this disparity may be due to a lack of information about the recycling programs, as 42% of respondents said they do not know what the term “single-stream recycling” means and 89% of respondents reported that if they knew more about recycling at Algonquin, they would be more inclined to recycle.

Gorman hopes to see not only students further their participation in Algonquin’s recycling program, but also teachers. He urges teachers to limit the amount of bins in their classrooms to one recycling bin and one trash bin; if a teacher has too many or not enough, he recommends they seek out a member of facilities to sort out the issue. Gorman believes that if teachers instruct students on how to correctly use the bins within their classrooms, students will be more likely to follow these expectations. If teachers have any questions, Gorman encourages them to seek him out to ask them.

“If there’s not a picture [in a classroom], because some might be missing, it’d be up to the teacher to say ‘Can we have another [single-stream diagram] put back up?’” Gorman said. “The responsibility goes on the whole team, students included… I’ve recommended a couple of times that the student body get behind it and get back into recycling, promote it, educate it and drive it.”

Junior Sasha Sheydvasser is particularly passionate about protecting the environment and has been working with Gorman and other faculty members to create new compost and recycling initiatives. She feels frustrated by the current state of recycling at ARHS and is inspired to promote better programs.

“Recycling is really bad at our school,” Sheydvasser said. “Basically, I see a lot of things in the trash that are recyclable, and also a lot of things in the recycling bin that are trash, which makes it bad for everyone because there is just so much that is wasted.”

History

The single-stream program, which was instituted in 2014, introduced the green recycling bins, in which all recyclable materials can be deposited.

In 2006, Algonquin introduced white paper recycling bins, which were in service until 2019 when the company responsible for collecting the paper, Midwest Paper Retriever, canceled their services. From that point forward, white paper was incorporated into the school’s single-stream program.

Gorman explained that it was the Science Department who coordinated the former white paper recycling efforts until the end of the program in 2019.

Despite local efforts, Environmental Science teacher Chrissy Connolly explained that a lack of effective recycling programs nationwide makes it difficult for schools to recycle effectively.

“Recycling in the world is disappointing, which therefore makes our school recycling not so good either,” Connolly said. “We were, in the past, led to believe that there was a lot more recycling happening than there really is. So the reality is most plastic will not be recycled, no matter what. If you put it in the recycling bin, it is not being recycled, whether it’s from your home, or school. It’s not just the school’s problem, this is a country-wide or a worldwide problem.”

Current Efforts

Although recycling effectively is challenging due to limited resources and access to quality programs, some students and staff are particularly passionate about reviving recycling and encouraging more sustainable lifestyles in general.

The Green Earth Club, led by Gould and senior co-president Ellie Westphal, hopes to organize a recycling drive later this year to encourage recycling of specific materials.

“Ellie and I were planning on hosting a recycling drive for one specific kind of recycling,” Gould said. “It could be like ‘Okay, we’re collecting recyclable paper,’ so then there’s not a lot of confusion on what materials can be recycled. We would make that very clear and get students to think about the things that they use every day that can [be recycled].”

Sheydvasser’s efforts to create student-led recycling programs began in middle school.

“In Trottier Middle School, I tried to create a compost bin during lunch, because a lot of things that were thrown away were compostable,” Sheydvasser said. “I have a compost bin at home, so I know how this process works, and it’s really cool. The amount of trash in those trash bins was sad to look at, honestly… I talked to different administrations about it, and what I learned was that there was a composting program beforehand, it just didn’t work. Trottier tried to do things and it failed, same thing with Algonquin. It works for some time, but then it just goes because of people not supporting it…I still need to figure out how to get people together so that it’s sustainable.”

Over recent years there have been conservation and waste reduction projects in the cafeteria, led by cafeteria manager Dianne Cofer. One specific initiative she has worked on is their ongoing effort to introduce some reusable silverware during lunch; however, she noticed a pattern of students routinely disposing of the silverware along with their trays.

“A lot of [the struggle] is funding, because you have to purchase all silverware and as your supply dwindles you have to keep purchasing,” Cofer said.

Cofer, however, does not rule out a return to these programs or others like them.

“Anything’s possible and it’s really got to have the students’ buy-in to support it and to utilize it the way it’s meant to be utilized,” Cofer said.

Gorman believes that change in the recycling program at Algonquin is possible, but only if supported by the whole community.

“Support from the teachers is huge,” Gorman said. “Without the support of the whole community we’re gonna end up just where we are [again].”

Ideas for Improvement

While recycling programs are imperfect, Connolly recommends that students and staff focus more on trying to reduce their waste in general, so there isn’t as much of a need to rely on recycling programs. Connolly recommends starting with reusable water bottles and cups.

“It requires a little more effort, as in you have to not lose it and you have to carry it around and you have to wash it, but there are plenty of options these days for reusable containers and cups and mugs,” Connolly said.

Gould also encourages waste reduction in addition to recycling.

“I think there’s a lot of things that people can do individually,” Gould said. “Recycling at home is a big one, but I also think just reducing your waste in general is a much better way to go because even if you separate your trash from your recycling, you take it to your local recycling station, only about five to six percent of plastic, in particular, is being recycled, and that’s a really disheartening number.”

Gould believes small changes to daily habits can have a big environmental impact.

“If you’re going to Starbucks or Dunkin’, bring your own mug,” Gould said. “Avoid disposable plastic as much as possible. If you are packing a lunch, you can use Tupperware instead of a plastic bag, which is what I use. I wash them day after day and you don’t have to throw them away.”

According to Gould, improved knowledge about recyclable materials could help community members recycle more effectively.

“There are some recyclables that are more effectively recycled than others,” Gould said. “Plastic is one of the worst ones… but paper and cardboard certainly get recycled more frequently, especially corrugated cardboard, the thicker kind. When people are doing the recycling, of course it’s important to try to recycle as much as possible, but there are certain materials that you can rely on more to be recycled.”

Sheydvasser encourages students to advocate for the change they want to see at ARHS.

“People should do their own research and fact check research on important things,” Sheydvasser said. “If we look at it from an external perspective, recycling affects all of us because it affects the environment.”

This story was originally published on The Harbinger on April 3, 2023.