Gray and brown buildings jut from fields of saturated spring grass. The dark asphalt streets starkly contrast with the light blue sky above. Along the horizon, the Green Line rumbles on its journey south. However, amidst this South Chicago spring scene is a colossal sea of crimson. 100,000 red tulips erupt from the earth over several plots of land representing buildings that had once stood and have been demolished due to the corrupt practices of redlining. In each coming year, these tulips will regrow, meandering and migrating from their original plots in a state of perpetual change, perhaps representing the lasting and unpredictable effects of redlining.

The tulips at the corner of 53rd Street and Prairie Avenue are part of artist Amanda Williams’ “Redefining Redlining,” a project that is both beautiful and striking, utilizing space, color and symbolism to convey a message that reverberates throughout the South Side, the city and the United States.

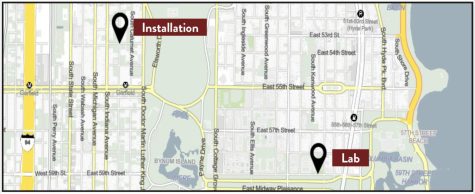

Ms. Williams, a Chicago-based artist and 1992 Lab alumna, often features themes of spatial justice and “the built-environment” in her work. This project focuses on the issue of redlining, a widespread range of real estate practices used to exclude marginalized groups from specific areas, which continues to contribute to the lasting segregation that exists in Chicago and beyond. Using old insurance maps, Ms. Williams, with the help of many volunteers, planted thousands of tulips bulbs last October in the place of 21 demolished Washington Park residential buildings.

Ms. Williams said part of the project’s inspiration was the visual connection of color and space to the abstract issue of redlining.

“So redlining is just a powerful term, in many ways, because it’s so illustrative. It illustrates itself. It’s a red, line” she said. “So I think having a term that’s identifiable, and then it’s so easy to translate into something visual, just kind of makes it a no-brainer in terms of something that I would be attracted to, given my love of color.”

Ms. Williams has used color to explore similar themes of the built environment before in the project “Color(ed) Theory.” In 2014 and 2015, she secretly painted multiple houses on the South Side slated for demolition in a solid and vibrant color. She intentionally used colors linked to products marketed towards the Black community throughout the late 20th century.

Today, Ms. Williams uses art to explore spatial justice, and her art is a product of the culmination of her experiences: specifically growing up as a Black person in two parts of Chicago’s South Side and studying architecture.

Ms. Williams said being trained as an architect and to think about how to move bodies through space has always been one of her preoccupations.

She said, “So my own spatial experience in relationship to Chicago was very influenced by going to Lab School and going between two different neighborhoods every day.”

Ms. Williams said that although she doesn’t think the project will solve the issues stemming from redlining, she believes the project can still have an expansive impact.

“There’s not an impact in terms of, ‘This is gonna solve the problems that redlining created in the first place,’” she said. “But I do think that there’s an element of understanding that things on a temporary basis can bring joy. They can bring imagination. They can sometimes bring about legislative change.”

She said her project is only a small part in exhibiting the impact of redlining and making a change for the community.

“I think I’ve understood that you can’t do a single action all of a sudden and magically impact the community,” she said. “This is one note on many points that are happening that aren’t just the work that I’m doing. It’s the work of other artists, of other organizers, elected officials, teachers, community groups, and so on and so forth.”

Even though Ms. Williams coordinated the project independently from the city and neighborhood with the permission of the landowners, she made sure to include and keep the community in the loop throughout the entire project.

“I think it’s always important to be a good neighbor,” she said. “So I made a postcard and mailed it to everybody in that postal zone and then also went door to door and chit chatted with folks, just to let them know that this project was coming up.”

She did the same before a celebration of the tulip bloom on April 29.

Because tulips are perennial and will regrow in coming years, Ms. Williams says an exciting part of the project is watching how it will evolve with or without her.

“I have no idea how much [the tulips] will adhere to the footprint that we created. If they’ll start to meander. If the neighbors will continue to steward the tulips after the project and the season of the blooming has ended. Will they invite me or other artists back to do things or will they do things themselves? These are all open-ended question marks that make this type of work so exciting,” she said. “You have to make the space for what the next iteration or evolution of a project is going to be.”

This story was originally published on U-High Midway on May 1, 2023.