Teenagers’ conversations on mental health: misusing clinical diagnoses, social media’s impacts, self-diagnosing

Emily Paschall

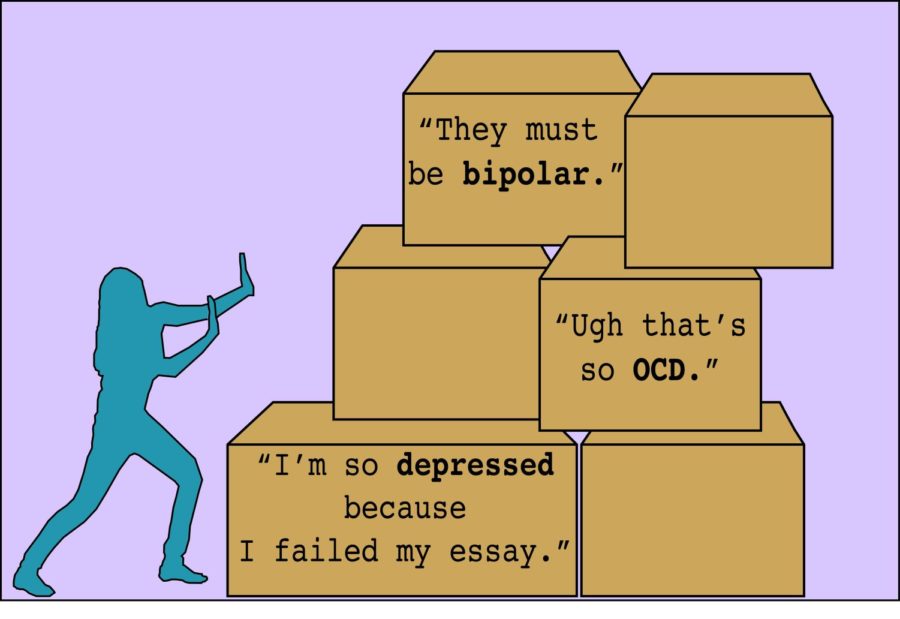

An individual pushes away boxes labeled with common phrases teenagers say that misuse the labels of mental health disorders. Clinical psychologist and author Lisa Damour said it is essential that people separate describing momentary feelings from clinical diagnoses to not diminish the experience of those who struggle with the disorder. (Graphic illustration by Emily Paschall).

May 11, 2023

When passing by groups of teenagers in the hallway, one might hear, “I’m literally so depressed because I just failed my math quiz” or, “Why are they so OCD about it?” Teenagers have been talking more about their mental health after the pandemic and more frequently using mental health-related vocabulary incorrectly in casual conversation. For example, the first phrase misuses the clinical diagnosis of clinical depression. The second phrase misuses the clinical diagnosis of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder or OCD.

An individual will most likely experience many sad and anxious emotions throughout life, but that does not mean they will be clinically diagnosed with depression or anxiety. Mental health is like physical health: every person has it. However, not all people experience mental health disorders.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states, “More than a third (37%) of high school students reported they experienced poor mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 44% reported they persistently felt sad or hopeless during the past year.” The rise in poor mental health in teenagers during and after the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked more conversation around mental health, especially in daily dialogue.

Clinical psychologist and author Lisa Damour‘s work focuses on the mental development of young women and teenage girls. Damour has presented to Archer students, faculty and parents about mental health in teenagers and how to talk about mental health. Damour said she has seen an increase in mental health disorders in young people.

“The data we have right now indicates that the pandemic was very, very hard on teenagers, which anyone who is with or around teenagers knows,” Damour said. “It has led to increased rates of anxiety and depression in young people.”

Freshman Caroline Collis was in sixth grade when quarantine began in 2020. Collis said the pandemic negatively impacted her mental health by making social situations more stressful.

“I do think the pandemic affected my mental health because I was in a developmental stage going through middle school, and being away from socializing affected [my] mental health,” Collis said. “I was more stressed being alone, and it made situations socially more stressful.”

Sophomore Francie Wallack volunteers at a nonprofit nationwide teen help hotline called Teen Line and helps teens with their mental health through calls, emails and messages. Similarly, she felt the isolation of quarantine took a toll on her mental health. According to the New York Times, worry about COVID-19 itself was very prominent in teens during quarantine, and Wallack said this affected her by making it more difficult to come out of quarantine.

“It was really hard to be so isolated and be without my friends, and so I think that was definitely hard,” Wallack said. “Also obviously worrying about COVID and just being super isolated also made it really hard to reemerge from the pandemic because there were just so many factors that weren’t an issue before so that added to my anxiety a lot, just reimmersing.”

Misusing Clinical Diagnoses in Conversations

According to the Mental Health Foundation, language and word choice are specifically important to pay attention to when talking about mental health and describing momentary feelings.

Senior and co-leader of the mental health club Kennedy Schultz described an example of a common statement that misuses the clinical diagnosis OCD. She also said that it discredits other people’s struggles with OCD and the overall effects on those listening.

“If you say ‘I like to color-code my stuff; like, I’m so OCD,’ it invalidates people who truly suffer with OCD. You are also educating people around you that that’s what OCD is — color-coding — when it’s really not,” Schultz said. “Obviously people suffer from it, and it’s truly a compulsive disorder. But by saying that color-coding is the same thing, you are invalidating people who suffer with OCD. Then if people aren’t educated about it, they will think, ‘Oh that’s the same thing. I [must have] OCD, too,’ and then it’s a spiral of people self-diagnosing.”

Wallack said she struggles with anxiety and often hears problematic phrases misusing the clinical diagnosis of anxiety disorder. She said academic stress can often cause people to misuse the term panic attack, which is an effect of anxiety disorder.

“It can definitely be really invalidating because I think mental health disorders are just really challenging. And I know I personally really struggle with anxiety, and, so, when someone is saying, ‘Oh, I’m so anxious, I almost had a panic attack,’ when in reality, it’s casual school stress, which I also feel and everyone feels — school stress is normal. I think it can be hard because since I struggled so much with it, along with so many other people, it just feels hard [to hear] at times,” Wallack said.

Damour said it is essential to understand that mental health disorders and negative feelings are separate things, so people can avoid confusing or misusing words describing either.

“It’s important to recognize that negative feelings are very, very much part of life, and we have a whole vocabulary for those too, that does not involve diagnostic terminology,” Damour said. “There’s real value in having a wide vocabulary for talking about feelings, because what we know is that when you’re more specific in describing the emotion, the act of talking about it actually is more effective in bringing relief.”

Self-Diagnosing

Highland Springs Speciality Clinic defines self-diagnosing as “the process of diagnosing or identifying a medical condition in yourself. [For the] majority of the time, people Google a symptom or medical sign and try to figure out if they have a condition, this is self-diagnosing.”

Damour said there can be harmful impacts of self-diagnosing a mental health disorder, as the individual may have symptom of multiple disorders at once and arrive at a conclusion that may be incorrect. She said any person should be careful and thoughtful when coming to conclusions.

“Clinical diagnosis is a complex process,” Damour said. “Psychologists … are taught to consider a wide range of factors beyond surface symptoms, when arriving at a diagnosis … difficulties occur … people can have more than a few things going on at once, and I would always want any untrained person of any age — not just kids or teenagers — to be very cautious about arriving at a conclusion that they suffer from a clinical diagnosis without doing so alongside someone who has a lot of training and experience in the world of psychological diagnoses.”

On the other hand, Collis said she thinks diagnosing can be very situational, depending on what mental health resources a person has access to, and, so, self-diagnosing might be a solution for some people. However, Collis said she thinks self-diagnosing should not be the main solution for people as it is misleading for the person.

“I know there are some areas in the medical field where it’s hard to really find help and get the diagnosis that you need. So I do see where the nuances come in,” Collis said. “I feel that it’s very situational because I feel that self-diagnosis maybe 20 years ago would have been all right because there [weren’t] as many resources to get diagnosed. There are more resources to find online websites and therapy. Although that is expensive, it is available. . . So while I feel that way, I feel that self-diagnosing does not need to be the option because there are other ways to be diagnosed, so you can have more credible knowledge about yourself and mental health.”

Social Media’s Effects on Mental Health Dialogue

According to Verywellmind, social media has been a central place of self-diagnosing and talking about mental health disorders in general. Surveys done at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry showed that “90% of teens ages 13-17 have used social media.” With such large numbers of adolescents using social media, conversations surrounding mental health disorders have become more prevalent.

Ninth Grade Dean Emily Gray said there are benefits and detriments of these conversations on social media.

“I do think that social media has sort of normalized mental health terms, which in a way can be great because it’s destigmatizing mental health,” Gray said. “But at the same time I think because it’s not necessarily an accurate description of what’s going on, it could be harmful.”

Wallack said TikTok is the first app that comes to mind to her when thinking about which social media app perpetuates ways of talking about mental health. She talked about what she thinks the benefits and detriments are of TikTok and Instagram.

“Tik Tok is much more casual than Instagram. People are just posting little 10 or 20 second videos about things which they’ll talk about [mental health] a lot. Instagram is more of formal posting. Something I’ve been noticing that’s positive is that people on Instagram will repost posts from mental health affiliated organizations, communicating why it’s not okay to be taking mental health disorders so lightly. [Teen Line] definitely posts a lot of stuff. So I’ll repost things on my story a lot of the time. Instagram is great for people spreading information about mental health.”

School counselor Jamie MacDonald has worked at Archer for four years. MacDonald said she notices that people often say being happy is a result of good mental health, but she said those are actually not related things.

“I do think that social media and just media in general, with the wellness industry, has definitely impacted the way we talk about mental health,” MacDonald said. “In media, there has been this push that we need to be happy. That means that we’re well, and those two things have been conflated, and that’s just not true. So the language used on social media has almost watered down or diminished what is actually happening, like the seriousness that’s happening for teens.”

To hear about Schultz’s opinion on the pros and cons of social media’s effects of ways of talking about mental health, listen to the audio clip below.

Future Steps

In order to avoid negatively impacting those with clinical diagnoses and avoid assumptions about mental health disorders, MacDonald said, open communication is essential.

“I think with anything with your peers, if something lands on you in a way that is uncomfortable, you check in with each other about it,” MacDonald said. “Open communication is helpful.”

Gray described what she believes a good response to hearing a mental health disorder misused in a sentence.

“I think a good response would be to question what a person is saying. So like, ‘Tell me more about that,’ because maybe they truly are describing a true diagnosis,” Gray said. “Then if not, sort of coaching them to reframe what they’re actually describing. So rather than saying ‘I’m depressed because I got this low grade on paper,’ saying, ‘Oh, I wonder if you can reframe that as I’m disappointed or I’m sad.’ Or something that’s a little more accurate.”

Damour said we should proceed using adjectives to describe negative feelings rather than mental health diagnoses.

“It’s important to recognize that negative feelings are very, very much part of life,” Damour said, “and we have a whole vocabulary for those too that does not involve diagnostic terminology.”

This story was originally published on The Oracle on May 7, 2023.