Allie Everhart

Despite a state law that says “A student may not be issued a monetary fine or fee as a disciplinary consequence,” students at MCHS continue to receive tickets from the McHenry Police Department for their behavior in school.

Still fine

Last year, a ProPublica and Chicago Tribune investigation found police issue costly tickets to students for misbehavior. Now, Illinois is attempting to ban the practice, which continues at MCHS.

Walking through the halls, a McHenry High School student notices fighting near the bathrooms. In response, a school resource officer nearby issues adjudication citations, or tickets, to the students. All of them are shocked, thinking that the school, not police, handled misbehavior.

Last year, ProPublica and the Chicago Tribune co-published “The Price Kids Pay,” a series of articles detailing how Illinois schools and police team up to address behavior. Reporters found that, over three school years, Illinois students received nearly 12,000 tickets for misbehavior, such as fighting, vaping and littering. Often, students faced additional consequences through their school. MCHS students received 255 tickets in the 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21 school years—seventh for most issued tickets, at least out of the schools investigated.

Reporters found tickets could come with fines reaching $750 — or more if students contested the ticket. Many municipalities, including McHenry, sent debts to collections at the time. Collectors could deduct from a parent’s paycheck or tax returns to pay the fines.

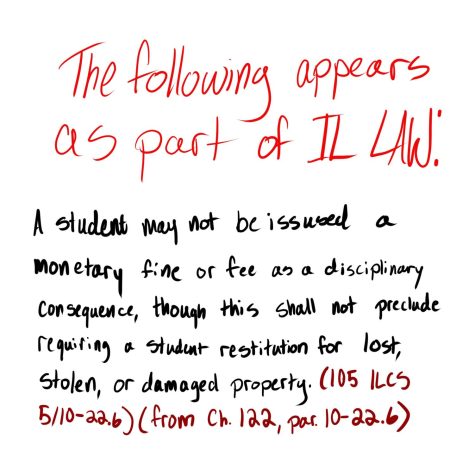

Two Illinois laws, Senate Bill 100 and 105 ILCS 5/26-12, state that schools may not issue fines or fees as disciplinary consequences. These were attempts to reduce the school-to-prison pipeline that pushes youth into the criminal justice system. Some argue ticketing is a result of loopholes within those laws.

Then-State Superintendent Carmen Ayala urged schools and police to stop ticketing students following the “The Price Kids Pay” articles. She noted how schools had “abdicated their responsibility for student discipline to local law enforcement.” Ayala recognized ticketing came as a result of loopholes in the law.

One year ago today, on May 19, 2022, the Messenger published “This is fine,” looking into how ticketing looked like at MCHS.

Students, administration and the police department all shared their varying perspectives. For one, the McHenry Police Department said they “[did] not agree with the insinuation” that issuing tickets at MCHS was working around Illinois law. Thus, ticketing continued for the remaining months of school.

And it continued this school year, too.

Context

These past few years, MCHS students have faced many challenges — a global pandemic, the change to Freshman and Upper Campuses, a move towards blended learning and a nationwide mental health crisis, to name a few. As a result, the school has faced problems with student behavior and attendance.

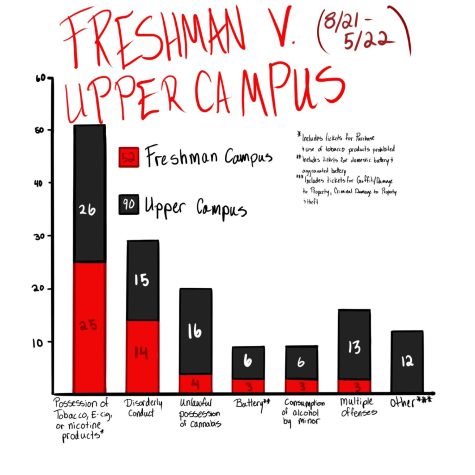

Police records show MCHS students received 223 tickets last year and this year combined for various misbehaviors.

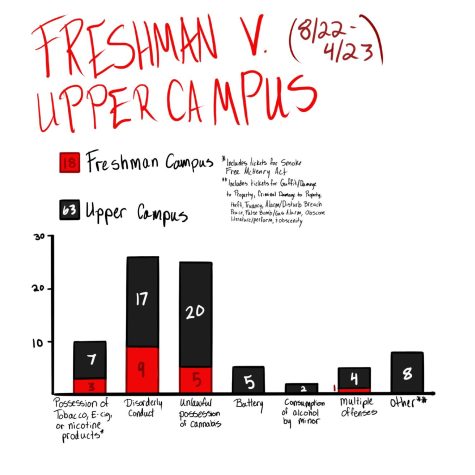

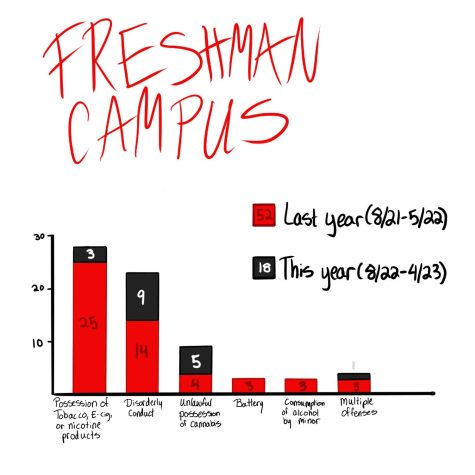

For the 2021–22 school year, police issued 52 tickets at the Freshman Campus, most often for possession of tobacco products and disorderly conduct. This year, the number decreased to 18, commonly for disorderly conduct and unlawful possession of cannabis. Records the Messenger obtained did not include data for May 2023.

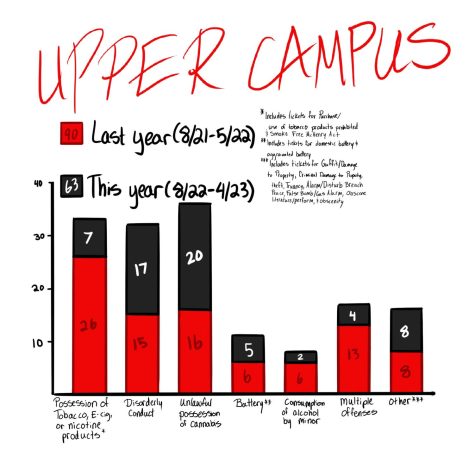

At the Upper Campus, which houses sophomores through seniors, students received 90 tickets last school year. These were often for unlawful possession of cannabis, possession of tobacco products and disorderly conduct. There were 63 tickets this year, most being for unlawful possession of cannabis and disorderly conduct. Again, records obtained by the Messenger did not include data for May 2023.

The most common offenses are all local ordinances of the City of McHenry.

Possession of Tobacco Products, ordinance 6-5A-31(D), includes electronic cigarettes, components, alternative nicotine products and liquid nicotine. Violating the ordinance is a “petty offense” and fined according to the Fines and Penalties Table on Title 15, Chapter 1 of the McHenry, IL Code of Ordinances. Not including other associated costs, the fine reaches up to $150.

Disorderly Conduct, ordinance 6-5A-4, broadly covers “any act in such unreasonable manner as to alarm or disturb another and to provoke a breach of the peace.” A fine of $200 comes with each violation, according to the Fines and Penalties Table — not including other fees.

Unlawful Possession of Cannabis, ordinance 6-5D-2, constitutes purchasing, possessing, consuming, or using cannabis if under 21 years old. Exceptions under the Compassionate Use of Medical Cannabis Program Act and the Community College Cannabis Vocational Pilot Program exist. The Fines and Penalties Table shows a fine of $200 plus other associated costs.

Overall, the fines for local ordinance violations range anywhere from $25 to $500, excluding other associated fees.

The Students

After bickering and arguing with a fellow student, junior Angelica Ferrell* got into “a physical altercation” at an Upper Campus bathroom. She is among the 17 students ticketed this year for disorderly conduct.

“I went home and had been home for an hour,” Ferrell described. “A police officer showed up and gave me a ticket.”

Similarly, senior Carolina Mendez* had a police officer deliver a ticket to her home — only that the citation was for her mother. Mendez was truant due to not being “in the right place and state of mind.”

A 2019 Illinois truancy law prevents school districts from referring truant minors to another public entity “for that local public entity to issue the child a fine or fee as punishment … ” However, McHenry ordinance 6-5E-3 says a child older than 13 or their parent, but not both, can be fined.

“[My mother] was called to the school for a meeting since it wasn’t just me not showing up, but my brother as well,” Mendez said. “From what I recall, the [officer] from the school was the one to give my mom the ticket.”

Both tickets came with a fine. Ferrell paid an initial $250 after pleading liable. She also received a 10-day suspension and no offers of counseling.

“They just kind of suspended me,” she said, “and that was it.”

Ferrell believes the suspension would have been enough and that “it is what normally should happen.” Not everyone gets a ticket for disorderly conduct, she says.

“I was kind of mad,” Ferrell said. ” … I kind of knew it was going to happen, but it was still upsetting because I had to go through this whole process.”

The students noted that their parents were upset and disappointed. For a parent, a ticket can bring awareness of their child’s behavior. But also, parents are often paying the fine or missing work to attend a hearing date.

“My mom was disappointed in me,” Mendez said. “I do think it was justified the way she reacted. There was a fine on the ticket … I can’t say more about [that] since our situation is more than just a truancy ticket. It became a more delicate situation.”

Ferrell also described that, often, the ticket extends beyond the fine and into a “social issue” at school. People talk about the ticket. And if anything, that “makes [a ticketed student] angrier.”

“The girl who I got in the altercation with would bring it up to get under my skin,” she said. “When kids know about it, they like to talk about it. I was annoyed, but I couldn’t say anything because you already have this stigma. You have to keep your cool, and you just kind of deal with it.”

Ticketing proponents claim a ticket brings attention to behavior. Mendez said she became aware of her behavior. However, the fine did not resolve the root cause of her truancy. For her family, the ticket was “another challenge we have to go through.”

“In the end, I’m still not doing well in school,” Mendez said. “I can say it only went as far as for me to just show up. [It did] not motivate me to do my work. My attention span is very bad, and I can only concentrate so much in school.”

All in all, Ferrell concludes that ticketing at MCHS for misbehavior should not occur. She says there are better ways to handle situations.

“You already get suspended for it, which is what normally should happen,” she said, “but they could offer better things. Like, if you needed to talk to someone, like a counselor, or figure something out.”

Despite pleading liable and paying a $250 fine, Ferrell continues dealing with her ticket. She had another hearing date in mid-May, showing up as a witness.

The state representatives

Ticketing students due to misbehavior on campus resulted from loopholes in Illinois law.

The Illinois General Assembly modified Senate Bill 100 in 2015 to state that “a student may not be issued a monetary fine or fee as a disciplinary consequence.” Since the language does not specify who can or cannot issue the fine, schools have been referring students to the police.

Schools fall under police departments’ jurisdiction, which allows them to ticket students seemingly without breaking the SB100 law. District 156’s lawyer was not available to comment.

Following the ProPublica / Chicago Tribune investigation, Illinois is trying to close that loophole. Chicago Democrat Rep. La Shawn Ford filed House Bill 3412 on Feb. 17 to amend the School Code.

“This bill is to ensure any behavior violations are referred to disciplinary and not law enforcement,” Ford said. “Right now, we see that certain behaviors are being reported to police [when they] should actually be reported to schools and principals. The goal is to not send students to police when they should be getting detentions and stuff like that.”

The proposed bill clarifies that students cannot be referred to another local public entity, school resource officer, or peace officer for a fine if the behavior “can be pursued through the school district’s available disciplinary interventions and consequences.” HB3412 is ongoing work brought to Ford by agencies and organizations seeking to protect youth and families.

“When you deal with ticketing, there is no real system in place for students to have a fair due process,” Ford said. “There is no due process in school ticketing, and students have to go to court alone and deal with these issues. They have to miss school. Parents are saddled with the debt of these tickets.”

HB3412 seeks to give schools and police a direction to support youth instead of involving the criminal justice system. While police would still handle criminal activity, schools would resolve all other misbehavior and handbook violations.

“Right now, what we see is that we traumatize students by involving police in situations [that] should be dealt with by social workers and counselors,” Ford said. “We immediately throw students in the criminal justice system instead of dealing with them in our school setting. We believe it opens up the school-to-prison pipeline once you have students involved with law enforcement.”

Ford adds that some want to keep ticketing to “skirt their responsibilities” and that it’s easy for a school to say, “I’m just going to call the police on this kid.” Though some have concerns over the bill, he believes “this is what we need” to support students.

“It will not make schools more dangerous,” Ford said. “If a student is breaking a law, then the police can be called. But, let’s say a kid is having a fight in the school — some schools will call the police. Is that something we should call the police for, or is that something that the school principal can actually handle? If there are no guns involved, no weapons involved, and kids fight in the hallway — we don’t believe that is something you have to call the police for.”

On March 27, HB3412 was re-referred to the Rules Committee. It will need 60 votes to pass in the Illinois House.

“Hopefully we’ll know something soon,” Ford said. “Right now, a few Democrats have been out, so it’s been tough getting our 60 votes. I hope we pass it before May the 19th. That’s my hope.”

The deans of students

In addition to two student resource officers, MCHS has three deans of students. They describe behavior as “significantly more challenging” than before the pandemic, noting increasing fights, vapes, and drugs.

“I think [behavior has] improved compared to last year,” Dean Brian Wilbois said. “I was a teacher last year, so I had a different perspective. I know last year there were a lot of challenges with the new building and learning model. I would say things are better, but with still more work to be done.”

The behaviors that are increasing are the behaviors receiving tickets. Up until April, there were 81 tickets issued this year at MCHS.

“We involve the SROs usually for things that we know are illegal, like fighting, battery, drugs, and things like that,” Dean Hilary Agnello said. “We involve them when we know something falls under that category. It’s not like, ‘I don’t like that kid. I’m gonna get the police officer involved.'”

Agnello explains that tickets are not “consequences” since SROs are only stationed at the campuses and are not employees. MCHS issues separate consequences for misbehavior.

“Consequences can vary,” Wilbois said. “Sometimes it’s a student conference, if it’s the first time it’s happened and depending on the severity. It could be a warning. We have detentions. And all the way, depending on the severity, it could be in-school or out-of-school suspensions.”

When referring students to SROs, though, deans ensure ticketing is used appropriately through consistency. For example, Wilbois says that any time a student has a THC card, the SRO is involved.

“We try to be very consistent across all the deans,” Agnello said. “We’re all very, very consistent. We talk to each other to make sure we’re not referring if things are personal or out of the norm. So, in terms of being fair, we really try to be consistent.”

Aside from a ticket and school consequences, there is counseling involved. Particularly for drug offenses, students meet with MCHS’ prevention and wellness coordinator.

“We do offer counseling,” Agnello said. “We always offer counseling. That’s a given. Not everyone takes it. You look both at the helping capacity, which we definitely do, but there’s also the matter of, if it’s illegal, it’s illegal. If you were caught at a mall or at a restaurant, and you were underage doing drugs or getting in a fight, it doesn’t matter where you are. That’s a police consequence.”

Ultimately, through ticketing, the goal is to reduce behaviors and create a safe school environment. Wilbois compared ticketing for misbehaviors to speeding tickets; they are deterrents.

“We are trying to create a safe environment,” Wilbois said. “An environment free of drugs, fighting, or weapons, just like [police] do outside of school. We are trying to make it as safe as possible for students and staff … I would hope [a ticket] serves as a deterrent. I’m sure, for some people, it’s a wake up call, and for others, that might not be.”

The deans are aware of HB3412 to end ticketing for disciplinary problems. Agnello believes the bill is not the right approach and would make schools “the only place where you can commit crimes.”

“I don’t want school to be the place where kids come to sell drugs,” she said. “If they find a place where they could do that without breaking the law, we’re going to get flooded with it. Plus, I don’t want people coming here and getting in fights. I don’t want people getting hurt. If they decide to [pass the bill], all they did was make a school the one place that you can commit crime. I don’t think that’s fair to the kids here who don’t do illegal things.”

Some see ticketing students and having them go through court as “traumatizing.” Agnello says the actions that warrant ticketing should in themselves be traumatizing.

“It should be scary to get caught selling drugs,” she said. “It shouldn’t be okay. It should be scary to be caught hurting someone. That should never be okay. So if you are doing something like that, I look at the victim. That is not fair to them. That is how I see it.”

The superintendent and state board

Last year, under Carmen Ayala’s leadership, the Illinois School Board of Education advocated against ticketing students. As state superintendent, Ayala sent schools an email imploring them to “immediately stop and consider both the cost and consequences of these fines.”

She said tickets create financial burdens and make students feel less welcome and included at school.

“ISBE continues to take a stand against punitive and exclusionary discipline, including under the leadership of [current] State Superintendent Dr. Tony Sanders,” Emily Johnson, ISBE press secretary, wrote. “Tactics such as tickets disproportionately impact students of color and increase the odds of students dropping out and experiencing involvement with the criminal justice system, which only harms families and communities.”

MCHS Superintendent Dr. Ryan McTague explains that tickets open additional resources for families and students. Since a ticket does not typically go on the criminal record, it serves as a way to potentially correct behavior without a permanent consequence.

“If you weren’t to write a ticket, the police actually would have the power to arrest that person because of the nature of the offense, whether it’s drugs or violence,” McTague said. “Moving through that ticketing format, hopefully, is a way to hold that student accountable and really talk with the student and family [about] the seriousness of that offense.”

ISBE knows that behaviors seen as defiance and misconduct “often stem from trauma students have experienced.” Because of this, the state board of education believes punitive practices are ineffective since they do not address the root cause of problems. McTague said ticketing is not “just about punishing you” and that counseling is available to students.

“I think we always try to work with students,” he said. “Let’s say it’s [a ticket] for using illegal substances at school. There’s definitely a referral to our coordinator and maybe an outside resource like Rosecrance [a behavior health and addiction treatment provider] to do a drug evaluation and start counseling. If there are further issues, and if kids are continually having conflicts, you might refer them to a social worker.”

Although helping students is a focus, so is maintaining a safe school environment. MCHS has “slowly changed a lot of our policies when it came to how students were referred” to SROs. “Pretty serious” offenses like disorderly conduct and unlawful possession of cannabis receive the most tickets now.

“I think you expect to go to a school that’s safe,” McTague said. “I think your parents expect to send you to a school that’s safe. If someone wants to physically assault someone else or if someone’s going to bring dangerous drugs into school, there’s definitely a school consequence. That’s also going to lead to an additional consequence with the police … in order to keep our school safe.”

Since last year, a concern with tickets has been the fine that comes with them. Local ordinance violations in McHenry range from $25 to $500, not including associated hearing fees. In Ayala’s email to schools, she mentioned that a $250 fine could be groceries for the week or a hearing bill. McTague said he would like to see a “restorative approach” to ticketing rather than fines, especially for lesser offenses.

“I would like to see less fine-based types of punishment and more community service-type punishments,” he said. “More towards the restorative angle of discipline and more towards a restorative angle of accountability — restoring the damage that’s been done to the community without just charging fines.”

McTague said that is what District 156 is working to do with the police department and McHenry County.

ISBE said they understand school leaders cannot single-handedly stop ticketing — and that legislation is needed. The board supports the proposed HB3412 to end student ticketing for misbehavior.

“Even after legislation is enacted,” Johnson said, “schools will need ongoing training and professional development to enact holistic shifts in practice and start approaching discipline from a trauma-responsive lens.”

At MCHS, there are already attempts to do that, balancing the need to maintain order while helping students. McTague said kids make mistakes but that a ticket can be a “wake up call” and prevent students from ending up in jail or using illegal drugs after they leave high school.

“The toughest thing to say is, “Hey, you made a mistake,’” McTague said. “But we love you. You’re still a part of our community. We want to make sure that [those behaviors] don’t happen again and that this wasn’t a life altering mistake.”

To increase understanding of trauma-informed practices, ISBE “has invested significantly” in training and support for schools. ISBE allocated $35.25 million to the Resilience Education to Advance Community Healing initiative and Social-Emotional Learning Hubs. Both assist districts in learning about and implementing ways to address trauma and mental health needs.

The police department

Through its partnership with MCHS District 156, the McHenry Police Department has one SRO at each campus. The SROs could not comment on ticketing practices. Instead, Commander Mike Cruz answered questions on behalf of the police department.

SROs are, first and foremost, police officers enforcing local ordinances and state laws. In the school setting, their duties extend beyond that.

“They are in schools primarily to ensure the safety of our student citizens and school staff,” Cruz said. “They are also there to mentor and counsel students and staff on a wide variety of issues, from general questions on law to helping find social services for those in need. Their function is literally in their title — ‘school resource officer.'”

All citations issued by them are for violations of state statutes or local ordinances. For “misbehavior,” there are no citations issued.

“Typically, school resource officers are either alerted or witness an incident,” Cruz said. “They then investigate that incident to determine if any state statutes or local ordinances were violated. If it is found [that one was violated], then a consequence could result in a citation or possibly an arrest. If the school resource officer determines no [violation], the incident would be referred to the school administration.”

Parents or guardians are informed of the incident and consequence when a student receives a ticket. The ticket comes with a court or hearing date, requiring a parent to appear present. The incident could appear on the criminal record, depending on the citation type.

“An adjudication citation is essentially a fine that is issued for an offense. Thus the offense … would not be recorded into the offender’s criminal history,” Cruz said. “Local ordinance citations … have a possibility of appearing on the offender’s criminal history. However, when an officer issues a local ordinance citation to a juvenile, the officer also issues them paperwork explaining how to have the offense expunged from their record.”

Last year, the McHenry Police Department did not believe ticketing in schools violated Senate Bill 100. Their stance appears to be the same.

“The McHenry Police Department enforces city ordinances as well as state laws in all locations that fall under our jurisdiction,” Cruz said.

Following the then-superintendent’s plea to stop ticketing last year, McHenry did not stop. The state superintendent does not govern law enforcement. Thus, the police department did not have to follow Ayala’s guidance. If HB3412 passes, though, there could be changes to how SROs handle issues at schools.

“If it is mandated through state statute that law enforcement alter our enforcement of local ordinances and state statues inside of school buildings,” Cruz said, “we will consult with our county State Attorney’s Office and follow their guidance.”

Conclusions

After being ticketed and paying hefty fines, students anxiously await to see the passage of HB3412 that could end ticketing for minor misbehavior. Though the ticket made them aware of their behavior, it did not solve the root cause of their issues. They think a suspension and counseling would have been enough.

Illinois is trying to close loopholes in the law, but in the meantime, ticketing continues at both campuses. Despite the different approaches and points of view, all are working towards a shared goal: protecting youth and creating safe school environments.

*Note: Angelica Ferrell and Carolina Mendez are fake names to protect the students’ privacy.

This story was originally published on The McHenry Messenger on May 19, 2023.