Intro

Homeschooling is the fastest-growing form of education in the United States. Citing statistics from thousands of school districts, The Washington Post reported that the number of families educating their children outside of conventional academic settings jumped 51% in the last 6 years. This percentage increased drastically after the beginning of the pandemic, and has held steadily ever since.

Trust within educational institutions is fickle. While these issues generally only concern irresolute school boards and angry cohorts of parents, more recently, the focus has shifted to students. Despite efforts to return to a pre-pandemic learning environment, many aspects of Clayton’s pedagogy and the student experience — for better or for worse — are unrecognizable.

While parents around the country see no recourse other than to remove their children from these adapting environments, it is decreasing trust in their children that has left school administrators with no choice other than to evolve. In this cover story, we will examine the causes and effects of student mistrust, as well as explore the implications of hasty — albeit necessary — administrative decision-making

According to Principal Daniel Gutchewsky, “As students had more of an online experience (…) it had an impact of diminishing the perception of the in-person experience.”

The Delay

Since the pandemic, schools nationwide have been making efforts to prioritize social-emotional learning recovery, which, according to Forbes, constitutes “the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships and make responsible and caring decisions.”

According to a report published last fall by EAB, an education consulting firm, 84% of teachers said that “students are developmentally behind in self-regulation and relationship building” in comparison to students prior to the pandemic. In addition, nearly 60% of teachers said that “pressure to boost lagging academic outcomes leaves them with insufficient time to address behavioral issues.” (The survey drew from 1,109 educators across 42 states.)

“I definitely think everything’s gotten a little bit more fragile,” counselor Tobie Smith said.

Smith has observed that students post-pandemic are about two years behind in their social-emotional development when entering high school.

“So for ninth graders, I think some of them are in the sixth or seventh grade, emotionally speaking,” Smith said.

During middle school, students begin to handle more advanced academic work and engage in social interactions with peers outside of structured playdates facilitated by parents, marking increased independence.

“The ninth graders spent most of their sixth and seventh-grade years at home. All of a sudden, they’re eighth graders and this is the first time they’ve slept at a friend’s house. All of a sudden, they are in high school, and according to books and TV, there is an idea of what they should be doing. I think many were kind of nervous and afraid,” Smith said.

She argues that this delay caused the largest impact on student maturity.

“The maturity just isn’t there. Social maturity that kids naturally have in freshmen and sophomore year, they didn’t have it because there was so much isolation,” Smith said. “I’m seeing in the ninth graders some ‘you know what, this isn’t who I am anymore. This was middle school me.’ But in some respects, we still have sixth-grade boys running around. We’re seeing sixth-grade behavior.”

Building off of Smith’s observations, Assistant Principal Drew Spiegel noted, “When students came back full time, I think that there was a lot of socialization that was lost that students didn’t really remember. (…) There was a lot of relearning of how we operate during school that needed to take place.”

According to Smith, fights traditionally do not occur at Clayton.

“We’ve had several this year,” Smith said. “In middle school, things are a little different. While it’s not common that there are fights, there’s that physical playfulness that middle school teachers observe. But in high school, we can’t play around like that. You can’t put your hands on somebody else and consider it a joke.”

Smith predicts that she will continue to see younger students making choices that past students would not make.

“They’ll get there, just maybe a little later than what we thought,” Smith said.

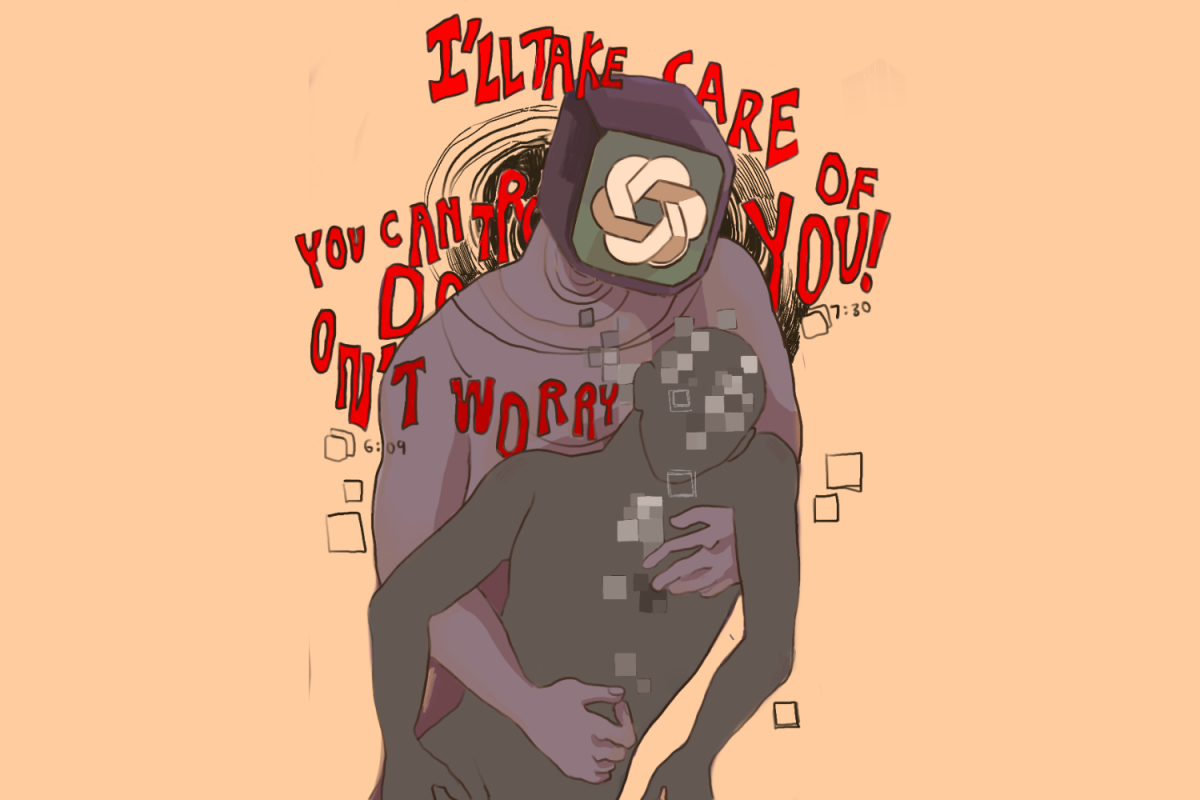

Another issue accentuated by the pandemic is adolescents’ increasing inability to handle stressful situations, Smith noted. Because the pandemic has brought national attention to the issue of declining mental health in teens, rather than being seen as opportunities for growth, stressful situations and natural feelings of anxiety have been demonized.

“We don’t always have to hit a huge alarm bell. We’re not always going to be able to protect everyone from ever having anxious moments or experiencing stress, Smith said. “We should be asking ourselves, ‘How do we teach to get through this moment? How can we use stress to build resiliency, rather than looking for a quick fix?’”

Smith highlights that over the past few years, she has witnessed some positive changes in student social-emotional development, notably emphasizing students prioritizing balance.

“During the pandemic, there was so much emphasis on self-care and taking a step back. Then students came back and said, ‘I don’t have to do it the hard way,’” Smith said.

Although the district has all but reverted to a pre-pandemic academic setting, according to Smith, many students have shown improved abilities to balance school, sports and sleep compared to the pre-pandemic period. Furthermore, she notes that the societal discussions that transpired during Covid have contributed to an enhanced awareness of student mental health by reducing the stigma associated with the issue.

“Students are more aware of social-emotional learning and are more in tune with how they are doing in that aspect than previous generations were,” Spiegel agreed.

Regardless of their positive impacts on student well-being, Smith acknowledges that these new trends in behavior are the antithesis of Clayton’s unspoken expectations of intense academic rigor.

“Academic pressures here are very real and very true. It can be a little bit of a pressure cooker (…) and I think that can be suffocating,” Smith said.

While many questions about student behavior have still yet to be answered, Smith advises against jumping to conclusions.

“I think that sometimes vast conclusions are made like, ‘oh this is due to this and we need to rush and change this.’ (…) Instead of always saying ‘this is what’s happening, fix it’, [parents and teachers] should simply be looking for ways to support their students,” Smith said.

The Snapback

According to data published last spring by Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, the average student at an American public school in grades 3-8 lost a half year of learning in math and a quarter year of learning in reading during the pandemic.

Students in St. Louis specifically — one of the hardest hit communities — lost over a year-and-a-half of learning in math during the pandemic, meaning teachers have to teach “150 percent of a typical year’s worth of material for three years in a row — just to catch up.”

Spanish teacher Dorotea Lechkova identifies increased phone use as one of the biggest issues in her classroom. This comes as no surprise, given that in a recent UK survey conducted by The Independent, 84% of teachers said their students’ attention spans are “shorter than ever” post-pandemic.

Lechkova believes that a large challenge to student attention in the classroom is the way online academic information is marketed to and consumed.

“Every online article is divided into bite-sized chunks,” Lechkova said. “You read the heading, scroll through the rest of it, read the heading, scroll through the rest of it, so you can keep clicking and scrolling and clicking.”

Websites such as The New York Times have begun tagging articles by the number of minutes they take to read, contributing to a learning experience that is the antithesis of what Lechkova claims “reading a dense academic text should be.”

“Everything is geared toward, ‘this is gonna be fast, this is gonna be quick,’ and it feeds into our attention constantly being divided into 100 different places,” Lechkova said.

However, she clarifies that this rift in focused learning should not be seen as a generational issue. Lechkova, who has a PhD in literature, noticed she no longer sits down to read for hours like she did a decade ago.

“How do you bring back the quiet time? How do you bring back the focus? How do you make your mind do these [academic] tasks again? These are skills that we’re gonna need to work on as a society, but [younger] generations more because [they’re] more exposed to all these changes,” Lechkova said.

In addition to shortened attention spans, Lechkova noted that the pandemic took a severe hit on student motivation, claiming that teachers have encountered difficulty teaching students who not only lack interest in the subjects that they are learning, “but in learning in general.”

“Parents would be surprised to see that their student is off task more than they thought. I also think they would be shocked to see the number of non-academic interactions that teachers are dealing with and how a large group with one teacher can be difficult to manage,” said eighth-grade math teacher AnnMarie Snodgrass.

Assistant Principal Dr. Regina Moore said the administration has also noticed a problem with time management. “Parents strive to send their kids to the school district when [they] move into the community because of the academics that we’re offering. So if we’re going to offer a rigorous and robust program, then there has to be some accountability,” said Moore

However, Lechkova argues that educators must also recognize the often-overlooked difficulties of being a student in a post-pandemic classroom.

“I have an issue with the term “learning loss” because I think we tend to forget the context of this pandemic, where we suffered this collective trauma (…) as a global society,” Lechkova said.

Covid accentuated many preexisting societal issues. According to the National Institute of Health, during the pandemic, many students were exposed to parents losing jobs, food insecurity and housing insecurity for the first time — not to mention grandparents and other family members falling ill.

“What does a student need to be able to learn? A student needs to feel safe. A student needs to be fed. A student needs to have gotten a good night’s sleep (..) So if those things aren’t in place, then the learning is a lot harder to do,” she said.

Despite these challenges, within the past year or two, Lechkova has witnessed a snapback.

“[There has been] significant improvement in academic performance, including study skills, preparation for class and general engagement the further away we get from the pandemic,” Lechkova said.

Despite the jump in academic performance, Lechkova agreed that parents often have the misconception that due to the pandemic, rigor was sacrificed in order to accommodate deficits in student learning. However, she believes that teachers should not be using the same teaching methods they used decades ago to teach a student body that is “living in a different world.”

“What might look like not as rigorous of an education to a previous generation, is not necessarily the case. It’s taking a different form. It’s taking a different shape,” Lechkova said.

According to Lechkova, during quarantine, there were upwards of 20 new digital platforms that students and teachers were required to learn. All of those changes that occurred at “light speed,” she argued, paved the way for many other changes to follow.

“One thing that has really changed, I think in a good way, about education is that classes are more collaborative, Lechkova said. “In class, students work in groups, have more hands-on experiences, and they didn’t use to get those opportunities.”

While it is difficult to quantify the exact impact of Covid on student learning, she notes that it would be careless to point to the pandemic as the sole cause of every change in learning.

“A lot of [these changes] were already in effect with social media with all of these other things,” Lechkova said. “Teachers are trying to evolve so we can meet students where they’re at and not force [them] into a way of learning that’s becoming antiquated very quickly.”

She also emphasized that many students lack the traditional skills that will always be imperative to learning.

“It’s important to know how to focus to read a text that’s more challenging and not give up. I’m trying to work on that a lot in my classes, but I know that when I give a reading with questions (…) a lot of students just don’t want to engage with that kind of task,” Lechkova said.

With the competing demands of school, social life and social media, compounded by societal stressors such as the pandemic, students and adults alike are essentially “living in a room filled with distractions all the time,” according to Time Magazine.

“I feel like we have lost some of the curiosity that students have had in the past,” Snodgrass said.

The Response

As the environment of school has shifted from an immersive pre-Covid atmosphere to an isolated, reformed post-Covid space, expectations for scholars have significantly shifted. With attendance worsening, according to Dr. Gutchewsky, and repercussions gaining severity, students and teachers alike have taken note of new responses to changed behavior.

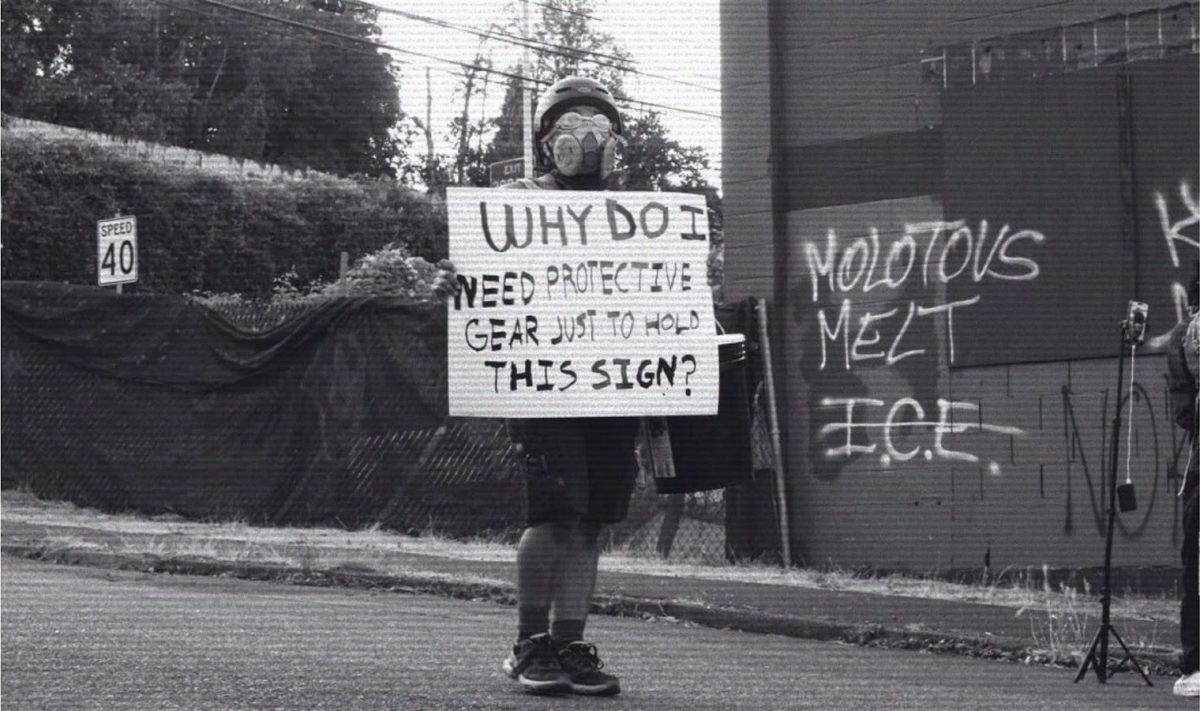

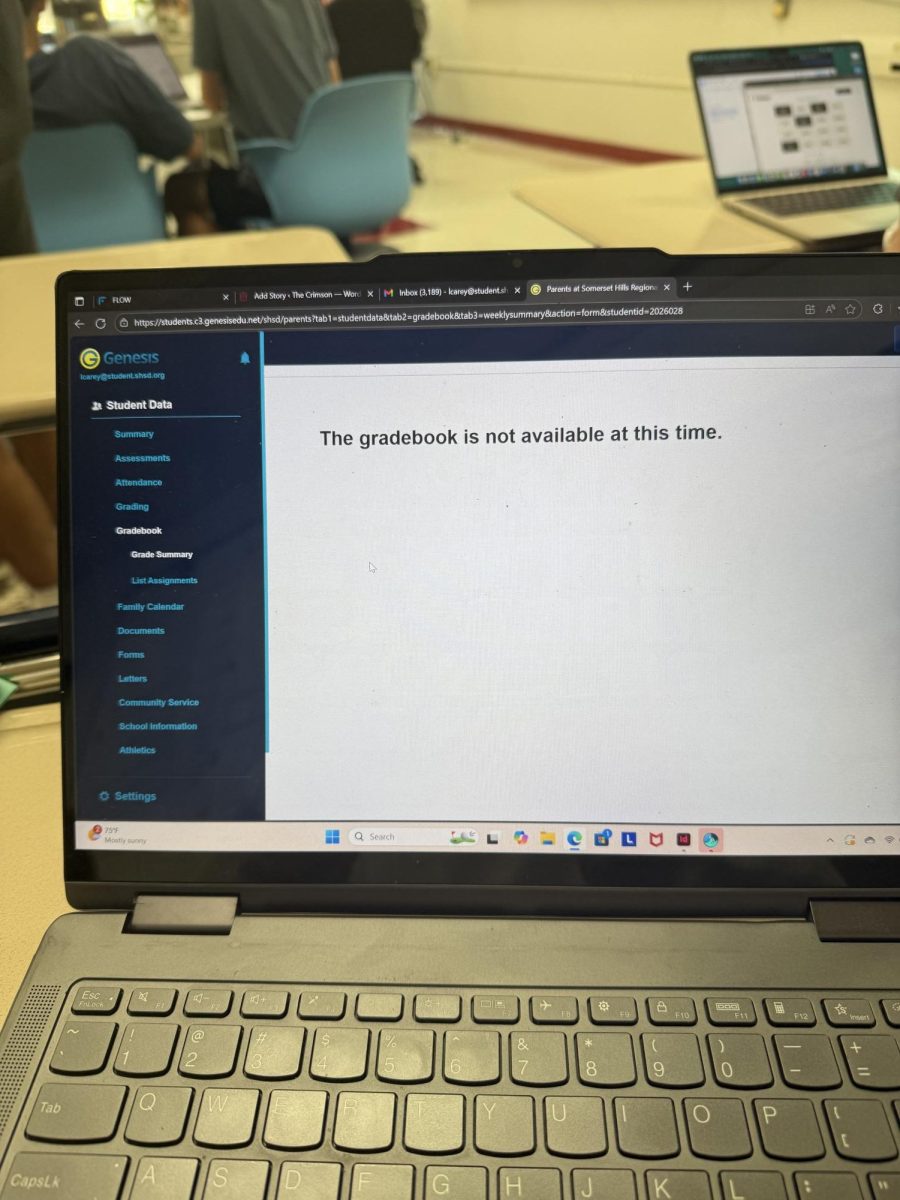

Administrators have had to deal with a rising problem of wanting to trust students and grant them freedoms such as open campus, using devices in class, showing up to detentions, and arriving on time to class, yet are consistently faced with abuse of those responsibilities.

Consequences have thus come naturally for those who fail to arrive to class on time after a 75-minute lunch or avoid serving a detention for two months.

“I mean, it’s a whole balance of freedom versus security,” Dr. Dan Getchewsky, CHS Principal, said. “So you have these great freedoms, but at the same time, there’s a cost because you expect people to use that freedom wisely.”

With the shift from a time of Google Classroom assignments replacing 80-minute classes to normal full-length school days, students had a naturally hard time readjusting to the rigorous schooling system previously known.

Gutchewsky noted that while 98 percent of students usually receive little to no detentions for attendance problems, “We try to focus our efforts on that 2 percent that are not using their freedom correctly.”

All of these behavior changes, more so in the student environment, had resulted in a lack of trust from teachers and administrators.

Clayton is unique because students hold key cards to the building. Students can unlock the front door, Stuber entrance door, and the CTE hallway door with their cards during school hours and may leave and reenter the school whenever they please throughout the day.

“Giving students all those things, like the key to the building off campus, has shown that we have given students the benefit of the doubt,” Dr. Regina Moore, CHS Assistant Principal, said. “But it’s when students don’t hold up their end of the bargain. It’s not us saying we’re giving you consequences; there are just natural consequences that are in place.”

CHS faculty face issues when students are not accountable for their tardiness and misuse class time.

“I think it’s more than accountability,” Moore said. “Teachers have expressed concern that students aren’t getting to class on time, or they’re leaving for an excessive amount of time without permission, or just not showing up.”

A lack of trust within the school environment has resulted in increased disciplinary responses and different practices for dealing with students’ mistreatment of responsibility, according to campus supervisors.

“Now there are some more rules that are being implemented, like detentions,” Moore said. “People used to go to detentions without having to be told to do so, while now detentions can go three, four, five months, and people won’t serve their detention. You may have seen campus supervisors pulling kids out of class to serve their detentions just to hold people accountable to the policies and procedures that we have here.”

Gutchewsky explained how while detentions from 15 years ago used to be all after school, now CHS is going to find a balance between lunch detentions and after-school detentions. However, weekend detentions are not up for discussion.

“I know somebody floated the possibility of Saturday detentions, but nobody wants to supervise or serve that,” Gutchewwsky said.

Responses to student behavior and a lack of faith from teachers have led to discussion of reforming these problems in the long term.

“My personal philosophy on discipline is there has to be consequences, but ultimately, what we want is to change the behavior,” Gutchewsky said. “The minimum consequence that could change the behavior is ultimately what we’re looking for.”

According to Moore, student safety is the end goal for administrators.

“We’re always crossing our T’s and dotting our I’s and making sure we’re doing everything we can to be the safest. There’s always going to be a loophole somewhere, but we’re trying to close some of those loopholes,” Moore said.

“Clayton High School is probably one of the only schools in the state of Missouri, definitely in St. Louis, that has an open campus policy for lunch,” Moore said.

Students are permitted to leave campus during their lunch periods and free periods. Many students use this privilege to explore downtown Clayton, spend time at home or attend appointments.

“If you don’t have class, you can go wherever you want. You can go to Straubs or go home or go to the park or go wherever. And that’s not typical, and sometimes people take that for granted,” Gutchewsky said.

According to NIH data, 37 percent of high schools nationwide have some sort of open campus policy. These policies range from late arrival and early dismissal only for select seniors to open lunch periods to a fully open campus for all students like CHS.

“We enjoy being able to treat students like young adults. We understand that many students who transition from Clayton will go to college, so we try to create this college type of atmosphere by holding students accountable to be where they need to be,” Moore said.

Many schools have modified open campus policies, where students must maintain a certain GPA and standardized test scores or obtain parental permission in order to access these privileges.

“In most places, you earn privileges, whereas we kind of just start by giving them to you and then assume that you’re going to use them correctly,” Gutchewsky said.

Yet increased absenteeism, school shootings, substance abuse and general misbehavior have led parents and administrators to question whether open campus remains the best policy. Even CHS modified its open campus policy during the pandemic, requiring that students remain off-campus for their entire free period if they elected to take one, eliminating traditional lunches and automatically placing students into study halls as opposed to free periods.

“Having an open campus is a privilege, not a right,” Christina Blankenship, CHS parent, PAC-ED president and Wellness Committee member, said.

Students use this privilege frequently, with many leaving campus during the day to purchase food, spend time at home or run errands.

“Open campus allows me to take breaks when school gets overwhelming, like taking a walk or going to get a coffee,” sophomore Samantha Cohen said.

According to Moore, “We have added adding Greyhound Time as a allows students to eat lunch for 30 minutes and get help from teachers or peers.benefited for kids to get help, but lunch is still technically only 30 minutes. “Most kids see Greyhound time and lunch put together and think it’s an hour and 15 minutes of lunch, and then they still come back late to school. There’s a problem,” Moore said.

Parents may also worry about the safety and location of their students during the school day. There is no school-based system to track which students are on or off campus at any given time.

“I don’t think anybody can tell me honestly that when students leave campus that all they’re doing is just going and having lunch,” Blankenship said.

According to data obtained by the school district’s Wellness Committee, CHS rates of alcohol and marijuana use are higher than state averages. Substance abuse peaks in the 10th and 11th grades. In addition, according to NIH data, open campus policies lead to lower rates of participation in the national school lunch program and increased consumption of sugary drinks and fast food. They also lead to higher rates of motor vehicle accidents.

Blankenship attributes much of this to the chasm of privilege and responsibility that exists between policies at Wydown Middle School and the high school.

“Freshman year is a very formative year because there is a huge difference between high school and middle school,” Blankenship said.

She believes that freshman students are exposed too much to older students who potentially engage in risky behaviors off campus during the school day. She worries about peer pressure encouraging younger students to engage in risky behaviors during the school day, in addition to the pressure they already face outside of school.

“Maybe we should consider getting rid of Open Campus, if not entirely, but for freshmen and sophomores,” Blankenship said.

The Public Health Advocacy Insititute lists fights, afternoon tardies, sexual assault, mugging, car accidents, arrest, truancy and substance abuse as risks of open campus policies.

“I think with all that we offer at Clayton, there’s not a need for students to go off campus,” Blankenship said.

Blankenship lists the recently renovated library, large commons, outdoor quad and Stuber Gym as on-campus attractions for students.

Due to the leniency of open campus, Clayton has the following absence policy: detentions are assigned after the accumulation of three tardies, and teachers may refuse to accept work from students with unexcused absences.

“If we have open campus, we have to be a little more hardline on absences because it’s so much easier to be out of class and not be accountable for where an individual is,” Joshua Hirschfeld, Campus Supervisor said.

A large part of Hirschfeld’s role involves notifying students of their detentions and supervising detention and in-school suspensions, along with monitoring hallways and supporting school safety.

“We have had an increased focus this year on making sure the students actually served their detentions and facing the consequences for missing class,” Gutchewsky said.

The open campus also increases the opportunity for dangerous individuals to make their way into the school because students are constantly leaving and entering.

Moore explained that “I think safety is one of the most important things on campus., and

“I believe things are changing. Not necessarily because students are bad or students aren’t being held accountable, but with the rise of shootings, we need to know where people’s kids are,” Moore said.

Prior to 2018, all exterior doors to the school were unlocked. After the Parkland school shooting, student IDs were implemented, and all students are now expected to scan their IDs to unlock exterior doors before entering the building.

“The first thing [the most recent security audit] said was the recommendation to close down the campus,” Gutchewsky said. “But [the security person] said to me, ‘I don’t imagine that in your plans,’ and I said, ‘We have to find a happy medium.’”

Gutchewsky sees these fears and pushback as part of a larger societal focus on safety, especially with regard to children.

“Let’s be honest, it’s not just the high school, it’s society. With air traffic cameras, cameras in public places and facial recognition software and all that kind of stuff in society, it’s that constant balance of freedom versus security,” Gutchewsky said.

Gutchewsky envisions an RFID card system in the near future, where sensors detect which student IDs enter and exit the building.

“Throughout my 23 years here, there’s been consistent support for maintaining the open campus. and I truly believe that if we talk about how we transition kids to the next stage of life, the vast majority of our students are going to go on to college, and when they go on to college, it’s not such a culture shock,” Gutchewsky said.

Despite its challenges, Gutchewsky envisions that the open campus policy is here to stay.

“No matter what happens moving forward, I think that the power of relationships and trust is always going to be central to education,” Gutchewsky said.

This was originally published on The Globe on November 14, 2023.