Throughout four years of high school at Latin, students take approximately 28 courses in total—varying in level of difficulty. Oftentimes, those courses and their levels of rigor can be sorted into three categories: “Easy A,” “Right on the Edge,” and “Brutal.”

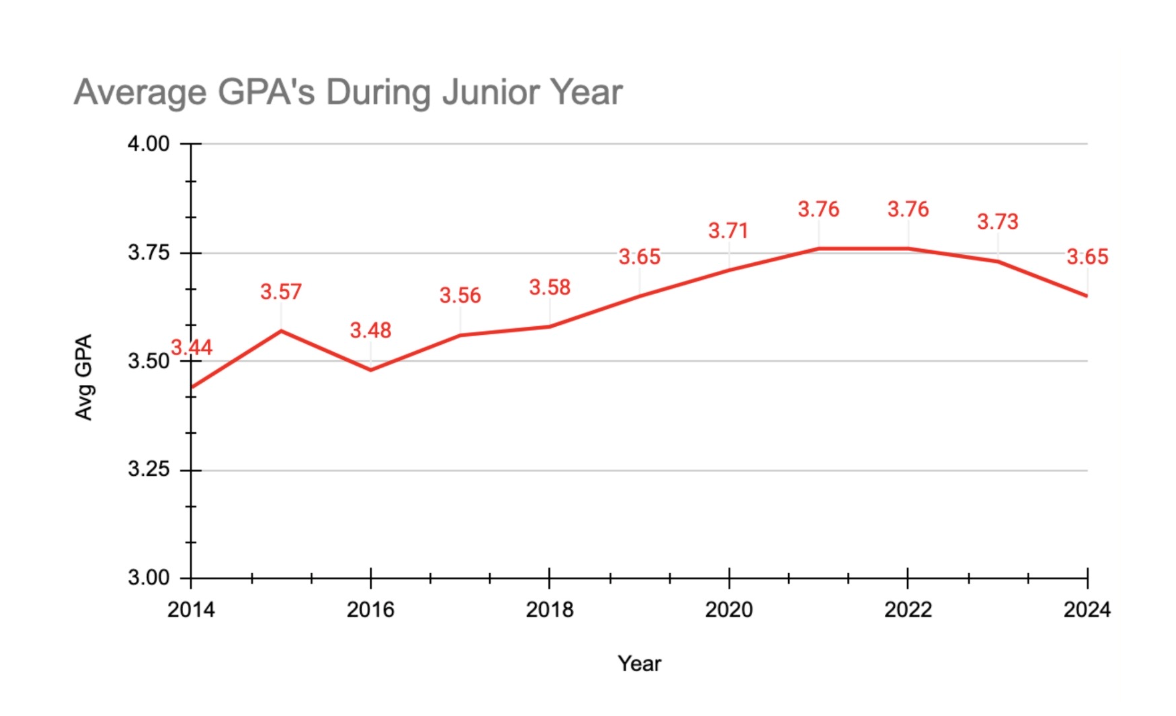

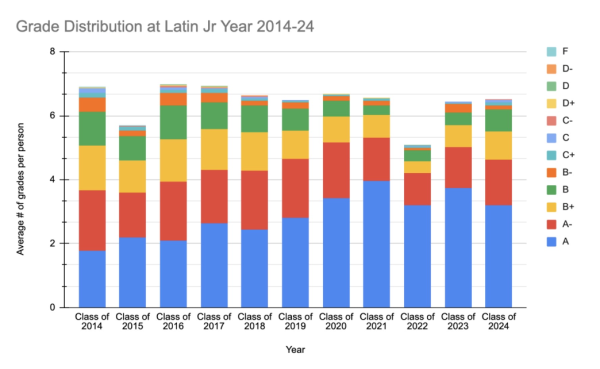

In 2021, ACT reported that, over an 11-year period, the mean grade point average (GPA) nationally increased from 3.17 to 3.36, and at Latin, that increase is even larger, according to numbers from Latin’s College Counseling Office. During their junior year, the class of 2014 held an average unweighted GPA of 3.44 and the class of 2024 held an average of 3.65.

It’s important to note that Latin’s data was collected over a 10-year period, three of those years being heavily impacted by the COVID pandemic. However, the increase in GPA at Latin was present before the class of 2020. In fact, after the class of 2022, there was a downtrend, implying a decrease in grade inflation. The class of 2024’s average GPA is equivalent to the class of 2019, one of the final “normal” years before the pandemic.

Senior Asher Bremen said, “I think grade boosting was really big during COVID-19 but has somewhat fallen off now.”

While Latin doesn’t officially calculate GPA, higher letter grades are becoming significantly more common as the years go on. During their junior year, the class of 2024 received 103.6% more A’s than the class of 2014.

Junior Jake Goldstein said, “I think it’s probably easier to get A’s these days. [Standards Based Grading (SBG)] makes it much easier to get an A, because you can take reassessments and it’s not averaged of all scores” per learning objective.

“Reassessing can inflate grades,” Upper School chemistry teacher Julie Plewa said. “You have this happen where there is a student, and they have had a B all year, and they reassess and reassess until they get the A-. But really, the hope is that you show a full understanding and that you really earn it in the end.”

“I actually think there are some times where grades are lower than they should be rather than higher,” senior Amalie Wong said. “With science SBG, the jump between an eight and a 10 is very drastic when the difference could be a tiny mistake.”

Some subjects such as English and history take the mode of all of a student’s scores, and with SBG, students are allotted a greater number of assessments and opportunities to prove their mastery of a topic or skill.

SBG aside, senior Gideon Heltzer said, “There’s always big opportunities, especially at the end of the year, to do stuff to boost your grade, so if you do that and study a lot, I think [getting A’s] is pretty achievable.”

However, Amalie disagreed. “In honors courses, I do not think grade inflation plays any factor in the final grade. There’s rarely extra credit or times where a teacher could help a person’s grade.”

As the number of A’s received increases, the gap between the number of A-’s, B+’s, and B’s continues to grow. The class of 2014, which had 108 students, got 193 A’s, 202 A-’s, 151 B+’s, 115 B’s, and 47 B-’s. The class of 2024, which has 123 students, got 393 A’s, 177 A-’s, 107 B+’s, 85 B’s, and 16 B-’s.

Including C’s, D’s, and F’s, the class of 2014 got 84 grades that were a B- or lower while the class of 2024 received only 40.

Junior Ajay Singh said, “I think the contrast from A’s to B’s in regular Latin classes, in my opinion, has a bigger difference and contrast than other schools.”

Each year, the College Counseling Office creates a school profile that is forwarded to any colleges Latin students apply to. It has information about SBG, Latin’s curriculum, and the school’s general approach to learning. Also included is the grade distribution from that specific class’s junior year.

Senior Phoebe Koehler said, “As grade inflation continues to rise, grades that were once considered above average are now perceived as mediocre or even subpar. It may seem hard to believe, but a B or B+ could now hurt your chances of acceptance into a prestigious university. It’s difficult for college admissions officers to discern meaningful distinctions between students’ academic performances as grades become more homogenous, so non-A grades tend to stand out.”

In an attempt to reduce stress levels for his Honors Precalculus students, Upper School math teacher Zach McArthur compiled a spreadsheet of the grades each of his students got over four years and the colleges they went to. Of the 59 students, six went to Yale University. Between those six, one got an A, three got A-’s, one got a B, and one got a C.

He said, “I would argue that in math, a B doesn’t stand out as a problematic grade because we don’t have wild inflation in math.”

To Mr. McArthur’s point, in English classes, 79 flat A’s were given to juniors graduating in 2024, while between both regular and honors math, there were 59 flat A’s. Comparatively, the class of 2014 had 33 flat A’s in English and 27 flat A’s in regular and honors math.

“I would imagine there are more A’s in the humanities, and I think there’s a cynical answer to that because the grading is more subjective in that maybe teachers are just giving higher grades,” Upper School English teacher and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Curriculum Coordinator Brandon Woods said. “I give a fair number of A’s, and I will defend that to the death. That’s because I do focus on growth, and I feel pretty confident by the end of the year that if a student has gained certain skills and can demonstrate that a few times, I weigh that more so than the cumulative.”

While grades may be more subjective in the humanities, Upper School math teacher Michelle Neely said, “In math, if you didn’t get x=5, it’s not correct. I can tell you exactly where your mistake was.”

Additionally, Mr. Woods noted that, in recent years, he has given students more A’s. “It’s not me trying to be political. I really feel that my process has integrity, and I don’t worry about it. And I recognize it as a problem given the reality of the college process. I think those two things can be true at the same time.”

Another reason that there may have been a greater number of A’s in recent years is the fluctuation between honors and regular classes, particularly math and science. At the beginning of each school year, students are allowed to drop from an honors course to a regular course if they are finding it too difficult. The idea is to keep some level of challenge, but also be making strides toward success. If a student isn’t showing signs of improvement, they may switch.

Mr. McArthur said, “I would say I give fewer C’s, but I think some of that is that families are more scared of C’s than they used to be, and those kids drop out of courses. Ten years ago, those kids wouldn’t have had those conversations as quickly and would have said, ‘I’m just going to try to get to a C.’”

Similarly, Upper School math teacher Chris van Benthuysen said, “That makes me wonder, could some of the inflation be coming from students being more willing to accept placement in a non-honors class for the sake of being able to be more successful? Or maybe briefly being in an honors class, having a rough experience, and saying, ‘I need to get to a place where I have opportunity for real success.’”

Grade inflation is a national problem, and at Latin, it can be attributed to many factors: pressure on Latin faculty to inflate grades, SBG, course rigor, and coddling students during COVID. Students are receiving more A’s than ever before.

Upper School history teacher Greg Gaczol offered a piece of advice for students: “Don’t let any specific number dictate who you are, how you’re doing as a student, who you are as a person. Don’t let it overtake other parts of you. Be proud of what you bring to the table aside from scores, grades, specific achievements, awards, and think about yourself as a total person.”

This story was originally published on The Forum on December 1, 2023.