Disclaimer: This article mentions suicide and violence against women

January 14th, 1963: Sylvia Plath’s first and only novel was published in the United Kingdom, just one month before her tragic suicide. Fearful that her mother would read the novel, Plath originally published her novel under a pseudonym, Victoria Lucas.

But what repulsive material could possibly be written in the pages of that book, so horrible that Sylvia Plath wouldn’t want to take credit for a creation that would one day be viewed as one of the best novels of all time?

Throughout “The Bell Jar,” Plath freely writes about topics considered taboo even to this day. Subjects like virginity, sexual assault, homosexuality, mental illness, suicide and birth control haunt each chapter. Banned for its mention of suicide, sex and profane language in the 1970s and still today in Indiana, “The Bell Jar”’s long-lasting legacy has been undeniably intertwined with notoriety.

While there is certainly an argument to be made about banned books being the most important to read, “The Bell Jar”’s importance spans beyond the deep controversy it has managed to stir. “The Bell Jar”’s tragic feminist message of wanting to be more than a wife, of feeling trapped under the patriarchy, of feeling as though the word ‘female’ is synonymous with helplessness unfortunately still resonates with modern women. Sylvia Plath’s classic novel asks questions about what it means to be a woman in modern society and helps us to examine the “female role.”

Though the progress women have made since the 1950s is significant, there are still so many ways in which men and women are still unequal. Many of the issues that women in Plath’s time faced have not disappeared but rather morphed and shifted into new obstacles. In addition to these long-lasting issues, the creation of social media has added new opportunities for misogyny and oppression of women to be carried out on a scale never seen before.

The premise of “The Bell Jar” and review

The story follows Esther Greenwood, a hopelessly cynical 19-year-old staying in New York for a coveted internship at a women’s magazine. Despite the apparent prestige of the internship, Esther finds herself disillusioned and further disappointed in herself for not appreciating the opportunity.

While in New York, she is continuously disappointed by the people around her, specifically, the men. One man in particular who continues to torture Esther is Buddy Willard, her high school sweetheart whom she is desperate to leave behind but unable to shake off. Buddy represents what Esther would be choosing if she chose the domestic pathway. He continually tries to break her into submission, even going as far as dismissing her passions by saying that a poem is a “piece of dust.”

Returning to her mundane life in Boston with her mother, Esther’s depression worsens upon rejection from a prestigious writing workshop. Dependent on academic pursuits for meaning, she spirals, grappling with the uncertainty of her future and envisioning various potential paths — such as a famous poet, a loving mother or an aloof spinster.

Esther aims to break free from the 1950s patriarchal norms, including the constraints tied to virginity. Despite the recurring theme of purity, she sees virginity not as a symbol of purity but as a burdensome weight. Liberation from it brings her relief. As she says at the beginning of the story, “I saw the world divided into people who had slept with somebody and people who hadn’t, and this seemed the only really significant difference between one person and another. I thought a spectacular change would come over me the day I crossed the boundary line.”

Contrasting Esther’s anticipation of losing her virginity, sex and promiscuous women are viewed as deeply unsavory in this paradoxical world. A man who tried to assault her labeled her a “slut” upon rejection. Additionally, Buddy — a traditionalist whose mother even told Esther to remain pure for him — had an affair during their summer separation.

Esther is trapped. Everything she struggles with, virginity, the patriarchy and stress about the future manifest into the proverbial “bell jar,” as Plath writes “[W]herever I sat — on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok — I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.” Esther feels that her depression descends on her, and she has no control over it. Her mind is her prison, and there is no escape, and she uses the metaphor of the bell jar as a visualization of this unrelenting torture.

As this is the 1950s, Esther undergoes electroconvulsive therapy, which proves ineffective against her depression. She makes an almost successful suicide attempt with sleeping pills, narrowly thwarted by her mother. This leads to a temporary stay in a psychiatric ward, prompting Buddy to end their relationship, leaving her with the question of who would marry her after being in a mental institute. A two-for-one line, serving as a a reminder that not only is marriage is the highest priority in a woman’s life, but being mentally ill taints a woman in a way that she can no longer serve her “purpose” as a wife and mother.

Within her lifetime, Plath redefined poetry and prose in the 1960s. Known as one of the pioneers of the confessional poetry movement — a literary movement in which authors wrote about issues that had traditionally been considered taboo — she and her peers changed the landscape of American poetry and literature. Confessional poetry served as a celebration of vulnerability, which was revolutionary in a world where mental illness and sex were dirty words.

Esther is not particularly likable — she expresses racist and homophobic sentiments, blames others for her problems and constantly feels superior — but she compensates with relatability to those who have experienced depression. Alone in her struggles, Esther faces a lack of understanding from those around her: her mother can’t bear to even look at her while she’s in the hospital, and her very presence seems to make some uncomfortable. Isolated in her “bell jar,” she intentionally distances herself from the other girls in New York and even the ladies in the psychiatric hospital who are going through the same things as her. She chooses to endure her suffering alone. Her primitive instinct to survive clashes with her human desire to die, vividly illustrated in her first contemplation of suicide where her heartbeat beats “I am, I am, I am.” Despite herself, Esther obeys this inner resilience, remaining captive of her body.

“The Bell Jar” is a masterpiece of poetry and emotion, and though Plath never got the chance to reach the height of the potential she had, “The Bell Jar” is as good of a legacy to leave as any. It remains as eye-opening to girls today as it was in the 1960s.

“She’s made it easier for other people to talk about women’s experiences. [It’s feminist] because she has goals for herself, and she wants to work,” junior Zoe Gleason said.

“The Bell Jar” concludes with a hopeful note for Esther, despite the harsh reality of her life as a woman. The first-person, past-tense narration suggests her improvement, evident as she prepares to interview with the psychiatric ward heads about returning to school. Although the tone remains cynical, Esther implies she has had a child and continues to write, demonstrating that overcoming societal restrictions on women, even after having children, is possible.

This, unfortunately, is not representative of Plath’s life. Reading what is practically Plath’s account of her own struggles, a feeling of unrest develops in the reader. While Esther escapes her bell jar, history knows Plath never did. The hope at the end symbolizes the optimism girls need to enhance their circumstances, emphasizing the importance of collective progress for women beyond individual struggles. It serves as a reminder to avoid losing sight of the end goal and succumbing to the cycle of depression in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges.

Women’s mental health throughout history

“The Bell Jar” is set in the early 1950s, a time more or less defined by the gender roles of the time. The woman’s role at that time was as a homemaker. Since people didn’t believe that a woman could both desire a career and be proficient professionally, the average woman was married by age 20. As a 19-year-old woman, Esther would have been expected to settle down very soon, which is why Esther’s desire to be more than a mother and wife and to be a poet and artist is such a large theme throughout the novel.

Considering the constrictive gender roles and limited options for women, it’s unsurprising that many housewives in the 1950s suffered from depression. This is primarily because of domestic abuse and childhood trauma. Though many people glamorize the life of a 1950s housewife, it was an inescapable prison for many women.

Women’s mental health has not been taken seriously throughout history. An example of this suppression was the diagnosis of hysteria. Though “hysteria” now means an uncontrollable display of emotion, until the 1980s, hysteria was a psychological disorder found in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The word hysteria came from the Greek word hysteria, meaning uterus. Ancient Egyptians also believed that the uterus could wander around the female body and cause excessive emotion. In a psychological context, hysteria is defined as a psychogenic disorder characterized by emotional outbursts, blindness, loss of sensation, histrionic behavior and hallucinations. Mysteriously, hysteria always seemed to only plague women, though it’s hardly mysterious at all because women’s emotions have always been seen as exaggerated.

The diagnosis of hysteria declined in the beginning of the 20th century, long before Plath was even born. But the effects of hysteria as a diagnosis definitely haven’t disappeared, and some may say it simply shapeshifted. Borderline Personality Disorder has been referred to as the modern hysteria. The symptoms of BPD include instability of affect, impulsivity, self-harm, and identity disturbance. And similar to hysteria, women are diagnosed with BPD far more often than men.

Why are women more likely to be diagnosed with BPD than men? The problem does not lie with the disorder itself — BPD is a real and treatable illness. The issue lies with the people doing the diagnosis.

People are socialized to accept displays of anger from men far more than from women. Men are more likely to express their anger with acts of aggression. This normalization of men’s anger and the perception of women as more emotional — despite this notion also being false — has led to disproportional diagnoses between the sexes. This is especially concerning since recent studies have even shown that men and women experience BPD at an equal rate.

Additionally, people who suffer from BPD may experience stigmas, such as people assuming they are unstable or blaming them for their condition. Even mental health professionals display bias against BPD sufferers when compared to other mental disorders. Considering that most BPD patients are women, this is not a shock. Female patients and their problems are very commonly dismissed and downplayed by doctors and healthcare workers.

Women can’t get the proper help they need if they are misdiagnosed because they are perceived as more emotional. And, on the flip side, since BPD is seen as a woman’s illness, by associating the disorder with hysteria, this is leading to the further stigmatization of mentally ill people, particularly mentally ill women, creating a vicious cycle of untreated mentally ill women.

“Women are seen stereotypically as the more emotional gender. So, we’re expected to treat our mental health with more of an open mind. Women are also seen as more emotional and almost unstable. Men are supposed to be unemotional and therefore they also don’t always take [the best care of] their mental health,” senior and co-president of Feminist Club Lacy Roberts said.

But even though women are thought of as more emotional — or “hysterical” — women’s mental health struggles are still dismissed. Many men’s rights activists argue that suicide is a primarily male issue, indicated by the fact that more men commit suicide than women. And while men experience unique mental health struggles that should not be invalidated, suicide itself is not even close to a uniquely male issue. In reality, women attempt suicide more often and simply opt for less violent less effective methods.

Creating a narrative that women’s issues are overrepresented, when they are not, and taken more seriously than men’s, which they are not, can have adverse effects on the mental health of young women. Conditions for women cannot improve until they, and their mental health, are actually taken seriously.

Causes for mental illness in women

So why are women today so unhappy? There’s a multitude of reasons. For starters, body image. By age 13,53% of American girls are unhappy with their still-forming bodies. Adolescent girls are witnessing unrealistic standards on social media. Exposure to social media positively correlates with eating disorders and low self-esteem.

While this is occurring, on the opposite side of the internet young men are being influenced by toxic alpha men. Examples of these men include famed kickboxer turned alpha male podcaster, Andrew Tate, who believes women are intrinsically lazy, cannot be independent and women should bear responsibility if they are victims of sexual assault. Before his ban on practically every social media site, he had accumulated 4.6 million followers on Instagram and 740,000 subscribers on YouTube.

Another similar figure is Hannah Pearl Davis, better known as Just Pearly Things on YouTube. Davis has almost 2 million followers and preaches obscene beliefs such as the idea that women should not be allowed to vote and divorce should be illegal. Her comments, however, are not filled with shock at her “The Handmaid’s Tale”-esque ideals, that women should have no say in government or their own lives but instead relief. Comments like “protect this one, boys” and “finally a good one” make up the majority of hers, referring to her eagerness to turn on her fellow woman in exchange for male validation.

When young girls witness these horrific accounts and the way misogyny from both men and women is valued, how are they expected to have any confidence in themselves?

And regardless of what Tate and his loyal cult of 12-year-old boys might believe, violent misogyny is alive and well. Around the world, 137 women are killed by a family member or intimate partner every day, and in America, three women are killed by an intimate partner daily, illustrating that women can’t even feel safe around men they should be able to trust. One in six American women will be the victim of an attempted or complete rape. The fact that almost 17% of women will experience one of the most traumatic situations a person can go through should be alarming to the general public.

And yet, these disturbing statistics are interestingly contrasted against 52% of Gen-Z and 53% of millennials surveyed who think that “feminism has gone too far,” and it’s now men who are being oppressed.

“Every single one of the themes [of “The Bell Jar is] still relevant. Life is still harder for women who choose an unconventional path. I’ve known since I was 21 or 22 that I didn’t want to have children, but when I said that, people usually told me that I’d change my mind, even people who didn’t know me at all. And there’s so much research about the motherhood penalty that affects women’s salaries — the fact that John gets the job over Jane when the resumes are identical — continued stigmas around mental health and the terrifying fact that many women in the U.S. can’t access birth control and other healthcare in 2024. I wish Sylvia’s story was a thing of the past, but it isn’t,” Hopkins said.

And any sense of autonomy or freedom women may have developed since Plath’s death is practically in vain. Despite making up 50% of the population and 50% of the votes, women make up less than 30% of Congress. In June 2022, four men and Amy Coney Barrett voted to absolve women of the right to autonomy over their own bodies. The government seems to have as much, if not more, stake in women’s bodies and lives than women themselves.

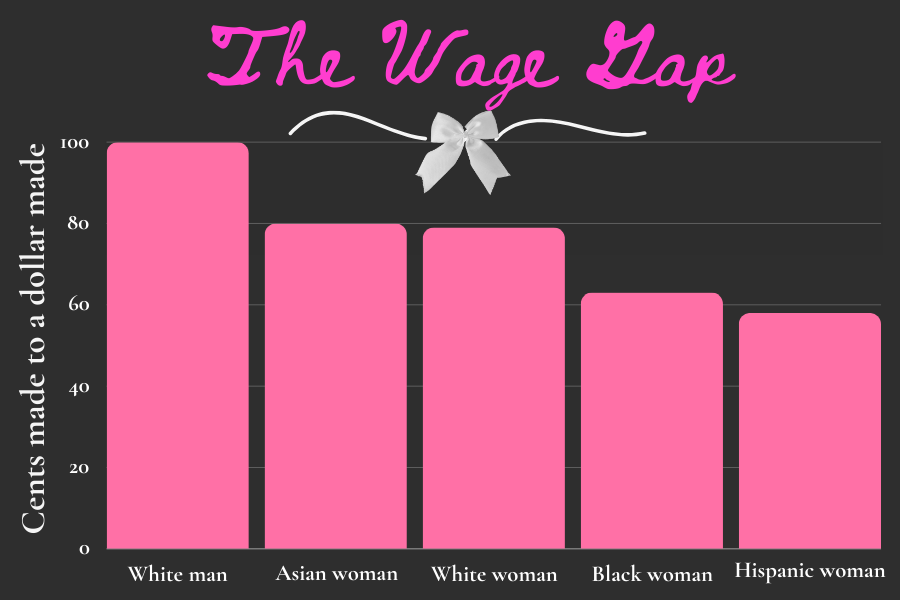

One issue that plagued Esther Greenwood was choosing between motherhood, the traditional female role and a career. This is hardly an issue unique to the 1950s, considering that we are still forcing women to choose between motherhood and careers. While mothers are technically able to have a job — about 71.2% of women with children do — it is hardly in the same capacity as fathers. Women with children find it far more difficult to find work than men with children, and when they do, they are paid less. The earnings gap in a heterosexual couple doubles in the first two years before a child’s birth and a year after, and the gap continues to grow for another decade. This phenomenon is often referred to as “the motherhood penalty.”

The damage having a child does to a mother’s income has roots in basic misogyny and women being turned down for promotions because employers believe that her child will always take priority over her career, and therefore she can’t take her job seriously. But more than that, it is logistically difficult to work as a mother. Maternity leave in the United States is 12 weeks, but it takes women six to seven months to physically and mentally bounce back after giving birth. It’s unfair to expect women to be able to come back after one of the most life-altering events that can happen to a person.

Even after coming back physically being a working mother is much harder than being a working father because most of the time, they are still being burdened with household chores and child-rasing responsibilities, illustrated by the fact that 79% of working mothers are responsible for doing the laundry and are twice as likely to handle the cooking. After coming home from a long day at work, the average American mother still comes home to even more work.

“In society as a whole, moms do the bulk of the child-rearing, the childcare, the cleaning, plus the cooking [and] maintaining doctors appointments. Not that no fathers do that, but it’s mostly the mothers who take that on,” science teacher and mother of two Suzanne Pircher said.

Poorer women have always worked while maintaining the house throughout history, yet before now, it was never looked upon as “the ideal,” or something a woman should aspire to. To recap the progression of women’s rights, in the 1950s, women had no choice but to be housewives. Now, women are still saddled with the role of housewife and the responsibility of work. Feminist win!

Societal pressure for a woman to give up individuality and her professional future in exchange for motherhood is a uniquely female issue. While fathers have to make sacrifices, mothers often report giving up their very sense of self after they have children. About one in seven new mothers experience post-partum depression, and many go undiagnosed because of their fear that others may judge them.

“[Being a working mom] is really tough. Working full-time and being a mom full-time is time-consuming. You’re exhausted, and you never get a break,” Pircher said.

Women are having children later and later which may help to curtail the vast amount that they are having to give up. However, there are more culprits for systemic causes of mental illness in women.

Misogyny in general leads to mental illness in women. Women who experience sexism in their lives are much more likely to suffer from depression. This is hardly a surprise, because misogyny can take traumatizing and downright humiliating forms for women, which of course affects self-worth and self-esteem. Living in environments where misogyny is heavily prevalent, women can begin to internalize these ideas that they are not as bright or as good as men, and that they are nothing more than sexual objects.

“Misogynistic comments can often lead to a feeling of insecurity but also an uncomfortable environment for a woman and that sets up that anxiety and depression. If you’re around misogynistic people and hearing that all the time, you’re not going to feel comfortable, you’re not going to feel happy because you’re treated very poorly,” said Roberts.

Sexual objectification specifically is associated with higher rates of anxiety and self-image problems. About 45% of women have had a sexual comment made at them in public and this frequently results in internalized self-objectification in women, a mental process that essentially leads to women seeing themselves as objects and in turn is associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety and eating disorders.

Smashing through the bell jar

Googling “how to improve women’s mental health” will procure recommendations for morning yoga routines and vitamin brands. While that’s all well and good, how can we make actually substantial improvements to women’s mental health? Since many of the causes of poor mental health in women are systemic and universal, there are many levels on which this issue can begin to be resolved.

The first one would be helped by heterosexual men taking on more chores around the household. Across all generations, women still contribute significantly more to work around the home. All families are different, and many husbands are more than willing to help equally around the house, but far too many don’t. Even millennial men, the largest generation of men to self-identify as feminists, are content to sit back while their wives take care of everything. By contributing to the home more, men can help to relieve the pressure off of their female partners.

And although men, especially those who are fathers, should already be helping around the house that they live in, this effort would be abetted by a federal paid paternity leave. While new fathers are entitled to a 12-week unpaid paternity leave, it’s unlikely that most American families can afford for both parents to stay home for so long. With paid paternity leave, new fathers can help their wives and begin to build habits of child care. This isn’t just good for the mother’s mental health, but it would also help with the post-partum healing period. Additionally, it benefits fathers who want to spend time with their children and unifies families as a whole.

Universal daycare would help mothers get back to work as well. While there is nothing wrong with being a stay-at-home mother, 45% of stay-at-home moms surveyed said that they would need affordable childcare to even consider returning to work.

The cost of childcare in Missouri for an infant child, meaning 0-24 months, is over $10,000 a year. In 2021, the average Missourian woman’s salary was $43,940, meaning that a woman would be sacrificing almost one-fourth of her salary for childcare. Furthering the glaring issue of the wage gap, this also points out the ludicrous cost of proper childcare. Universally affordable daycare is a must to balance the playing field for working mothers and fathers, and will also subsequently help the 155,868 single-mother households in Missouri.

On a community level, Parkway counselors should be trained in recognizing warning signs in teenagers but they should also be trained in recognizing warning signs specific to girls because those can often manifest differently.

Mental health should also become a valid reason to miss school. It’s far too often assumed that mental health days are an excuse to miss school, but mental health impacts a person physically, commonly causing fatigue, headaches and digestive issues. Like sick days, they should be seen as a necessity for all teenagers, but especially for teenage girls who experience a menstrual cycle. This is because PMS — premenstrual syndrome — can often cause symptoms of depression in girls, and it’s unfair to expect girls to function the same these days.

Individuals can help by volunteering at or donating to women’s shelters. Speaking up when misogyny occurs is necessary. Many people just don’t realize the gravity of the issue, evident in the fact that 77% of men believe that they are doing all that they can to support gender equality. It’s impossible to speak for every man who felt that way, but the truth is, that’s wholly unlikely. Simply not being misogynistic isn’t enough to combat misogyny, one must make a decision to actively defy it when it’s perceived.

Most men are uncomfortable when they see sexism, but they overestimate how sexist their male friends and colleagues are, which makes them less likely to intervene when they perceive misogyny. However, it’s been observed that speaking out against misogynistic behavior lessens misogynistic attitudes within men, demonstrating that speaking out against misogyny is the most vital factor in dismantling sexism in society. It may seem embarrassing or awkward to call out a friend for saying something that may be intended as a harmless joke, but what a person says often shapes what they believe.

Like the end of “The Bell Jar,” the future of all women’s mental health is ambiguously hopeful. Women’s rights have progressed majorly since Plath’s time. On an individual level, treatment for mental illness in women is very much possible, but since misogyny is such a systemic issue, nothing can be done without nationwide changes.

Sylvia Plath once wrote “I desire the things that destroy me in the end” in her personal journal. Ultimately, this proved to be true. But throughout her life and with “The Bell Jar,” she established a legacy that helped many girls to open their eyes to the misogyny that has enveloped them and realize that they should not be restrained.

“There were huge open-ended questions for women and what their role in society would be, could be, should be at the time the book was published. There had been other feminist works in literature. But ‘The Bell Jar’ is one of the first times you see a woman who has choices. Esther is free to explore career and relationship options, even though the patriarchy and her resulting mental health struggles make it hard, and we get to see what that looks like. And although she deals with depression, she doesn’t die [or become] crushed by it at the end, unlike most of those earlier literary examples. There’s hope for her future when we leave her,” Hopkins said.

This story was originally published on Pathfinder on January 15, 2024.