Somewhere within McLean High School, a seasoned educator is finding themselves at a crossroads. Wrestling with the weight of prospective decisions and a growing sense of disillusionment, they contemplate whether the relentless demands of their profession are enough to bear, or whether it would be more appropriate to leave in favor of a job with better compensation and treatment. As the rigor of their teaching demands begin to outweigh any benefits, the decision to leave shifts from being a question to a resolution.

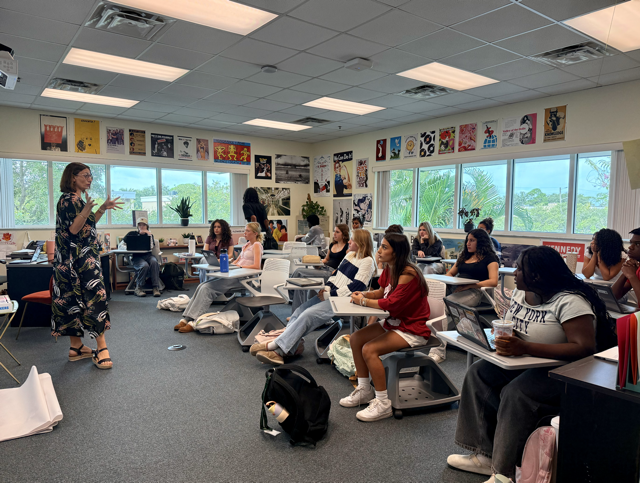

In 2019, McLean’s English department lined up for a photo in the courtyard, sunlit smiles on their faces. Five years later, just 12 of the 23 teachers in the photo still remain at McLean.

Within just the first semester of the 2023-24 school year, the teacher shortage has had a glaring impact on classrooms, with many students noting the last-minute efforts to obtain substitute teachers and new full-time staff to fill in gaping holes.

“Getting a new teacher was a big adjustment for me because Ms. Donoghue left roughly halfway through the year, meaning she had already become close with us and we had become used to her grading style,” said junior Veronica Buzzi, a student in Dr. Valerie Puiatti’s class—formerly Bridget Donoghue’s class.“She also knew our abilities pretty well, and with a new teacher we had to learn [her grading style].”

The teacher shortage has taken the country by storm and thrust the issue of teacher pay into the forefront of discussions. Policymakers are confronted with the imperative to address the glaring disparities and to ensure that teachers are fairly compensated for their contributions—a sentiment more agreed upon by policymakers than ever before.

For years, experts have been raising the alarm about low matriculation in the education sector. The pandemic—coupled with preexisting inadequate pay—intensified these issues and pushed primary and secondary schools across the United States to the edge.

Inadequate income

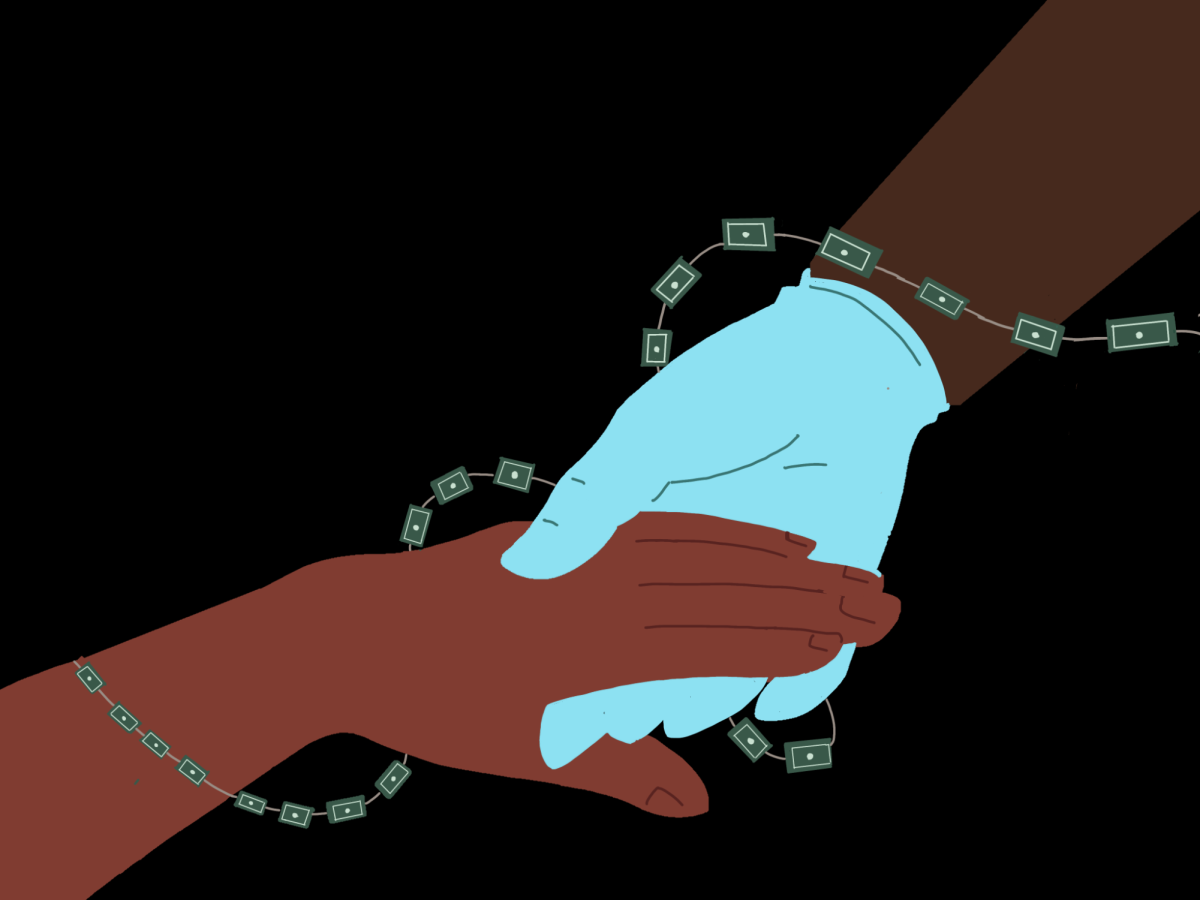

Insufficient teacher pay is the foundation of today’s teacher shortage. Both before and after the pandemic, teachers in Fairfax County and across the nation have faced wage issues.

Teacher pay is determined by two factors on the Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) pay scale: years of experience and level of education. An FCPS teacher with a bachelor’s degree earns $63,004 after five years of experience, and a teacher with a master’s degree earns $77,210 after eight years of experience, as per the pay scale’s exact income determinations. Incremental increases in pay as teachers gain years of experience are called “steps.”

Since the start of the pandemic, some pay steps have been condensed to not provide raises each year. This year, the second, third and fourth-year steps on the FCPS pay scale, each of which corresponds to a full year of teaching experience, have been combined into a single step—two more years of teaching yielding no incremental increases in pay. The school division’s “pay scale squishing” contributed to physics teacher Christopher Dobson’s decision to leave teaching temporarily and pursue software engineering in San Francisco in hopes of one day returning to the profession.

“I was stuck on what really should have been a previous step,” Dobson said. “This was a budgetary thing that FCPS did…They’re just going to decline to give teachers their regular expected salary bump for one year or two years to save the school district money.”

Though three years have passed since schools restarted operating traditionally, FCPS has not yet resolved the issue of condensed pay steps. What began as a pandemic-era measure to cut costs has so far been maintained by the county.

“[FCPS] can freeze our salary at any time. I’m in my seventh year [of] teaching. I make what a fifth-year teacher makes,” English teacher Diana Glaser said.

These pay freezes add up over time. In Glaser’s case, she would have earned over $5,000 more this year had her pay not been frozen. The resulting insufficient pay often forces teachers to pick up jobs over the summer to make ends meet.

“I’ve talked to teachers who have worked as [standardized test] tutors and private tutors in general. There’s one teacher I know that goes to Pennsylvania and does work at a museum over the summer,” Dobson said.

However, finding these summer jobs can prove to be difficult for teachers given the flexibility necessary and the short time frame.

“There’s a structural problem whereby we have about eight weeks to 10 weeks over the summer. No one really wants to hire you to do competent, skilled work if you’re only going to stick around for eight weeks,” Dobson said. “The only jobs that teachers can reliably get are seasonal work, work that has a definitive end date, is incredibly flexible [and] doesn’t require a very long-term time commitment.”

In addition to concerns about frozen pay and second jobs, teachers have reported having to work unpaid overtime to finish grading all of their assignments, in part because FCPS-provided planning periods can be too brief and infrequent for teachers to complete their required grading.

“FCPS needs to give us more planning time. I have at least two to three meetings every week during my planning period,” Glaser said. “If I only have five planning periods, that’s almost more than half where I don’t get to grade or plan. So then my labor is forced to be outside of the classroom, which I refuse to do.”

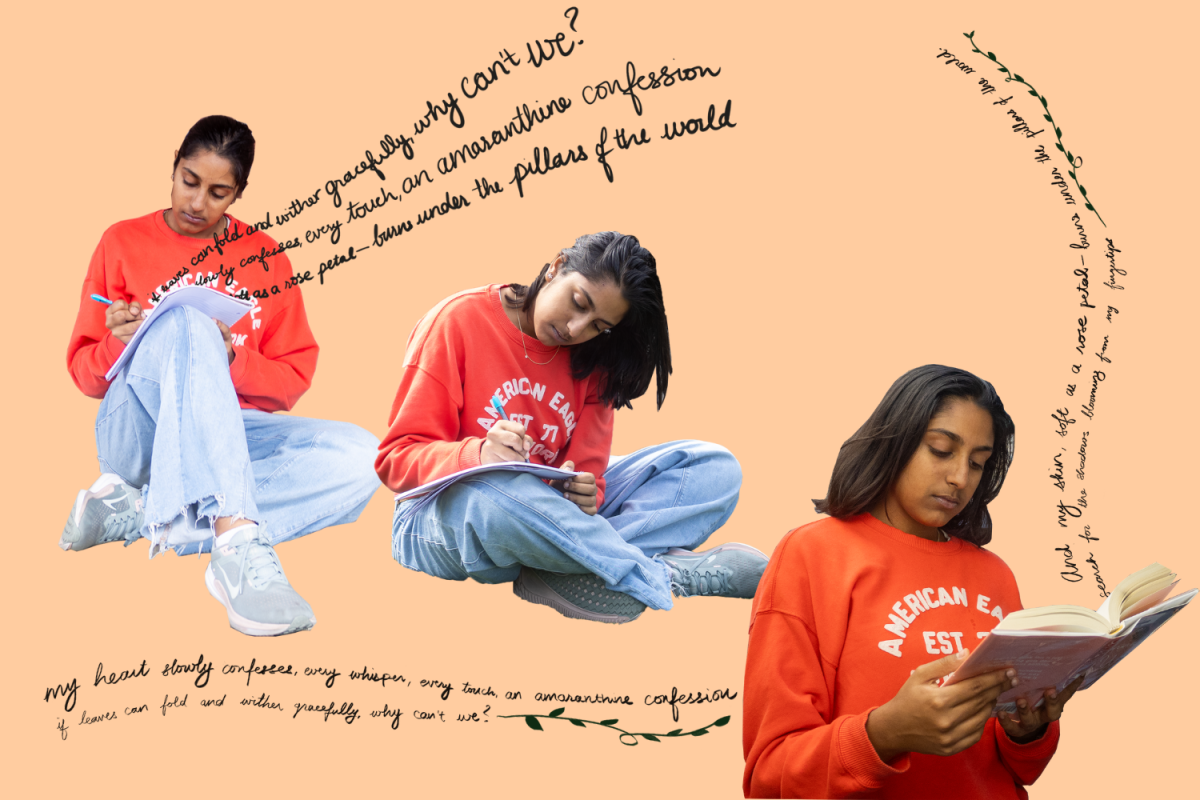

In the English department especially, the immense amount of paper-reading and grading can be impossible to complete within FCPS paid periods. The unpaid overtime required by her job was one of the reasons former English teacher Rosalie Clements chose to pursue a non-teaching career.

“When you’re an English teacher, each kid does a five-to-ten-page paper. You have 100 plus kids; that’s hundreds and hundreds of pages of grading that you have to do, but we would have to do them at home,” Clements said. “A lot of us would spend our evenings grading papers until 10 o’clock at night, some nights.”

Given the exorbitant cost of housing in Northern Virginia, living close to McLean is simply not an option for many teachers. According to the prominent real estate service Redfin, the median house listing in McLean sells for $1.3 million—far too steep for someone on a teacher’s salary, forcing educators to find housing elsewhere. In some cases, McLean teachers can spend two hours round-trip commuting to work.

“I live in Centreville, which is a 30-minute drive away. If I leave after seven, it can be 45 minutes to an hour,” Glaser said. “I looked at places around here… I can’t afford [them]. I can’t live in this community.”

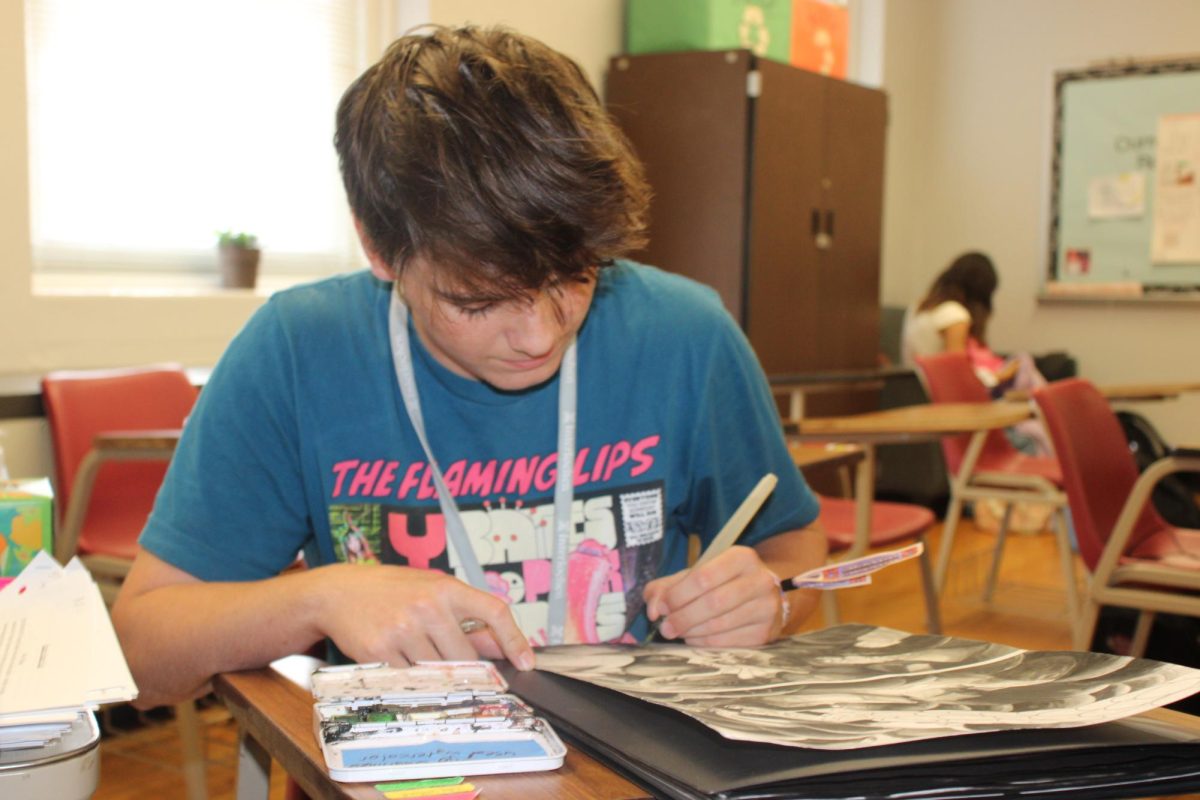

“In terms of teacher burnout, more and more is being piled on teachers. It’s been too much. There are more responsibilities with the politics of it all, especially for the English teachers that have a lot going on with reading books and making sure that they’re right, So you have increased responsibilities and a workload that is not feasible in order to still have a private life.” — Senior Karina Bhatt, who directed a documentary on the teacher shortage.

COVID as a catalyst

As the pandemic arose, teachers were faced with the unprecedented situation of virtual learning. The virtual learning dilemmas—loss of learning, little to no interaction, technical difficulties and poor communication from the school division—mounted over time to create disproportionate stress for teachers.

Teacher burnout has always existed, but the phenomenon was aggravated by the pandemic and continues to take a severe toll today. According to the 2023 Virginia School Survey of Climate and Working Conditions, 39.2% of FCPS division teachers reported that they are experiencing burnout. Teacher burnout was also the main reason English teachers Bridget Donoghue, Elise Emmons and Rosalie Clements all decided to pursue non-teaching careers.

“Teacher burnout is huge. Think of a presentation, in any of your classes. But imagine that you are giving an eight-hour presentation where you have to have all the materials, you need to be able to answer any question that pops up and you need to be able to give reliable information,” Glaser said.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, many teachers discovered that the shortcomings in student performance were compounded by pandemic-era learning loss. These adverse effects on students translated into an increased workload for teachers, who grappled with their students’ considerable setbacks in both academic and social-emotional development.

A survey conducted by the Institute of Education Sciences in July 2023 revealed that 36% of public school students were lagging behind grade levels before the pandemic. In contrast, after the pandemic, 56% of students performed lower than grade level.

“In terms of teacher burnout, more and more is being piled on teachers,” said senior Karina Bhatt, who filmed a documentary about the teacher shortage. “It’s been too much. There are more responsibilities with the politics of it all, especially for the English teachers that have a lot going on with reading books and making sure that they’re right, So you have increased responsibilities and a workload that is not feasible in order to still have a private life.”

Further, the number of graduates entering the education field has rapidly fallen; according to the Pew Research Center, the number of university students receiving bachelor’s degrees in education has declined by 19% from 2001 to 2020, and 48% from 1971 to 2020. Combined with the national exodus of teachers, the decline of the education major has caused the number of teachers to dwindle like never before.

“We’re going into our job fair season. Our jobs are to assess new hire candidates and invite them to the job fair,” said Tim Hilkert, an FCPS employment specialist. “For 10 years when I did this, everybody wanted to be a grade one through three teacher. A lot of them liked to work with primary students and the candidate pool was in the thousands. We have 143 elementary schools…[now] we don’t even have 143 total candidates that have applied.”

Similarly, at McLean, hiring qualified teachers has become far more difficult in the years since the pandemic.

“[The teacher shortage] is starting to impact us because there’s no competition [anymore],” Principal Ellen Reilly said “I used to have all these different choices [for a position], and I’d have to turn people away. I don’t know if I turn people away like I used to.”

Measuring mistreatment

The effects of COVID go further; following the pandemic, teachers face blatant disrespect in their professional lives, more so than before. The lack of appreciation from the community combined with financial strain significantly contributes to the reduced number of educators across the country.

“I am not treated like a professional. I’m treated like a babysitter. I have a master’s degree and two undergraduate degrees. And when I get into meetings, sometimes with family members or even with students, I am treated like I am not the expert in my field,” Glaser said. “We don’t treat other experts in their field the same way.” —Diana Glaser, English Teacher

The disrespect towards teachers has intensified in the current state of the education system. Simple acknowledgments and acts of gratitude have become increasingly scarce, further isolating teachers in their struggles.

“My ninth graders, before the pandemic, would come visit me, write me notes or even just say thank you after class. I don’t get that at all anymore,” Glaser said.

The education sector is marked by unwavering commitments. Educators navigate challenges which seemingly surpass the stress levels met in other careers.

“My dad was deputy director of the CIA for 37 years. When he retired, he went into teaching. He taught Latin. He put more work into being a teacher, and more effort and care and everything else than he did for the CIA. It was much more stressful,” Reilly said.

According to a 2022 school staff survey conducted by the American Psychological Association, 49% of the teachers revealed that they had serious thoughts of quitting due to increasing mistreatment from both parents and students.

“I am not treated like a professional. I’m treated like a babysitter. I have a master’s degree and two undergraduate degrees. And when I get into meetings, sometimes with family members or even with students, I am treated like I am not the expert in my field,” Glaser said. “We don’t treat other experts in their field the same way.”

Parents often fail to give the teachers the professional respect they deserve, treating them in ways inconsistent with the demands of their roles.

“You have to show the teacher as an adult—with a degree, at their workplace—respect. I wouldn’t go to the dentist and start screaming,” Clements said. “But parents come to schools and start screaming and yelling about a B versus an A-minus, and [teachers aren’t] treated as adult professionals.”

The lack of appreciation extends beyond the interpersonal realm to the institutional level. Teachers, who invest their time and expertise into educating the next generation, often find themselves feeling undervalued by the county.

“At the end of [every] year, we have an end of the year banquet, and Fairfax County recognizes the teachers that have been [there] for sometimes [up to] 40 years, and the gift that they give us is a lanyard,” Glaser said. “Some people are here their entire careers right in Fairfax County to get a lanyard. That’s what we do.”

Despite a variety of individual reasons driving teachers to leave, former educators share a common sentiment: appreciation for teachers must be restored. Among the teachers firmly holding this understanding is Elise Emmons, who taught in McLean’s English department for years. Emmons subsequently left mid-year to pursue a non-teaching career.

“Just show teachers respect. Give them the respect of letting them work from home on teacher work days, give them a modicum of control and respect and it will go a long way,” Emmons said.

“What we don’t realize or what people do not understand is that the teacher shortage is actually going to become worse. No systemic or institutional changes are being made to address the issues that we’re seeing within education.” —Diana Glaser, English Teacher

A look to the future

The current shortfall of qualified educators will likely have substantial long-term impacts. Some of these impacts include larger class sizes and substandard overall education in the areas hit hardest. While McLean has not reached this extreme, the teacher shortage’s national impacts are definitive.

On Aug. 31, 2022, the White House announced a plan to “strengthen the teaching profession and help schools fill vacancies” via a set of private and public sector partnerships and negotiations. Two years later, the teacher shortage remains pervasive nationwide.

The 2022 announcement was not the first to offer a solution to the stagnant teacher wages against rising inflation. In 2019, before taking office, then-presidential hopeful Kamala Harris made a bold pledge in her campaign: she promised to work towards “an average $13,500 pay raise” for American teachers. Five years later, with Harris as the second-in-command of the administration, the plan has come to no avail.

“What we don’t realize or what people do not understand is that the teacher shortage is actually going to become worse,” Glaser said. “No systemic or institutional changes are being made to address the issues that we’re seeing within education.”

Various measures exist at different levels to address the teacher crisis. The core of the issue is associated with low wages, and a substantial pay increase has the potential to deter teachers from leaving the profession. Allocating increased federal tax funds to public educational institutions could allow county-level executives to offer sustainable wages for teachers as well as improved healthcare and retirement plans.

“I feel like there are a lot of programs and a lot of initiatives that the county spends money on, but frankly, are unnecessary,” Bhatt said. “In some way, shape or form funds need to be reallocated because I would say teachers have a priority and everything else takes secondary importance.”

There is also an increasing need to establish long-term solutions to foster teachers of the future. Encouraging students to receive an education degree and pursue teaching as a career path is an integral step of the solution process. To support the next generation of teachers, FCPS created the Teachers for Tomorrow program, a program that guarantees education students teaching positions after college.

“The Teachers for Tomorrow program is seriously one of the best programs in McLean. It really teaches students how to actually teach, as well as numerous different skills that help you in both your future and professional endeavors,” said senior Joseph Kingsley, a Teachers for Tomorrow student.

Amplified by the pandemic and prolonged by teacher mistreatment and unsatisfactory pay, the teacher shortage is not expected to be resolved in the coming years unless serious change is made. Unless an ambitious national or state-wide program to fund teachers is enacted, the teacher shortage will remain an issue, and its impacts will be seen in classrooms across the country.

“A lot of really good teachers have already left,” Emmons said. “What’s left are teachers with little to no experience that are just going to continue the cycle once they ultimately realize this profession is not sustainable in the long run.”

Teacher Spotlight

The Highlander spoke with multiple former teachers at McLean over the past weeks—some of whom who have left the teaching profession all together and some who have transitioned to other position. Below are profiles of some of those teachers.

Bridget Donoghue

Bridget Donoghue—one of the most recent exits from McLean—was a teacher in McLean’s English department for nine years and the department chair for two years before setting off in December to become a school-based technology specialist at South Lake High School. Donoghue cites burnout as the primary cause of her mid-year decision to leave, although she still works for FCPS.

“With English teachers, it’s especially hard because we grade so many essays and written assignments that we spend most of our time outside of school,” Donoghue said. “In addition to doing just teaching, we’re asked to do a lot of other things [and it can get] overwhelming. I didn’t have a good work-life balance.”

The burnout faced by Donoghue during her time teaching at McLean was aggravated by the inadequate salary provided by the county and a lack of compensation for the extra work she took on.

“Paying teachers more and then taking stuff off our plates [will help solve the shortage], because a lot of times we act not only as teachers, but as counselors,” Donoghue said. “We wear a lot of hats, and something has to be taken off that plate in order for teachers to stay.”

Rosalie Clements

A desk piled with endless grading, a herd of angry parents and another underpaid day all led to Rosalie Clements saying goodbye to her McLean and her teaching career. After seven years, she knew it was time for her to leave in July 2022, following her first year back into in-person teaching. Clements is currently employed as a Program Manager within Maryland Judiciary.

“I was the first [of multiple] English teachers to leave because of how overwhelming it got to be,” Clements said. “At the end of the quarter, I would use my sick time and call out of work, and I would just sit at home and grade for 12 hours.”

Clements was faced with insurmountable disrespect in her final year of teaching, which became one of the primary reasons for her career shift. English teachers in particular are often labeled as strict or unfair graders due to the subjective nature of the study.

“I had kids who would bring thank you notes and tips and things like that,” Clements said. “My last year of teaching, I was getting threats.”

Elise Emmons

Elise Emmons, a former English teacher at McLean, left her teaching career behind in November 2023. Emmons now works as a Senior Manager of Digital Learning at the American Academy of Otolaryngology—one of the leading organizations focusing on the medical field on conditions related to the ears, nose, and throat—a field drastically different from English education.

“I am a project manager for a program in which I facilitate the creation of curriculum and assessments between otolaryngologists and otolaryngology residents,” Emmons said. “This includes recertification for doctors as well as learning certifications for residents.”

Emmons attributed increasing pressure leading to burnout as a main reason for her leave. The concerning trend of educators leaving to non-teaching careers has been noticed by teachers and students alike.

“The pressure of grading and providing feedback for every assignment, coupled with the considerable pressure exerted by parents, created an environment that made it hard to create a good atmosphere of learning,” Emmons said. “The absence of adequate support from admin further intensified the challenges in the profession.”

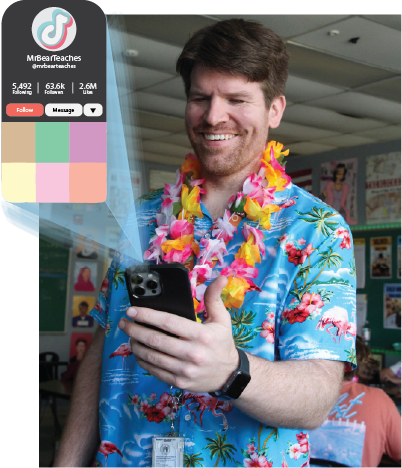

Christopher Dobson

Christopher Dobson now resides in San Francisco working in software development utilizing programming languages, writing websites, cooperating with data scientists and managing products—a stark contrast from his time at McLean. For five years, Dobson combined his passion for physics and teaching to work in McLean’s science department. However, he ultimately opted to withdraw from the teaching profession temporarily to pursue a higher-paying career.

“The cost of living in McLean and Northern Virginia [was] just too high for my salary and benefits as a teacher,” Dobson said.

Despite the harsh reality stemming from financial difficulties, Dobson expressed appreciation for his teaching career.

“Becoming a teacher was the single best decision I ever made for myself. It made me happier as a person,” Dobson said. “I absolutely see myself going back to teaching one day…but [with software engineering], I could at the very least build a nest egg for myself for a few years.”

This story was originally published on The Highlander on February 7, 2024.