The United States has a complex and interesting history, especially when it comes to Supreme Court cases.

There have been a multitude of cases surrounding First Amendment rights, such as Tinker v. Des Moines, which established that students are entitled to First Amendment rights in schools as long as it’s not disruptive. Some, however, weren’t as lucky as John and Mary Beth Tinker.

As a part of her advocacy for student press freedom, Cathy Kuhlmeier often travels to schools and conferences to speak about her experience with censorship and press freedom.

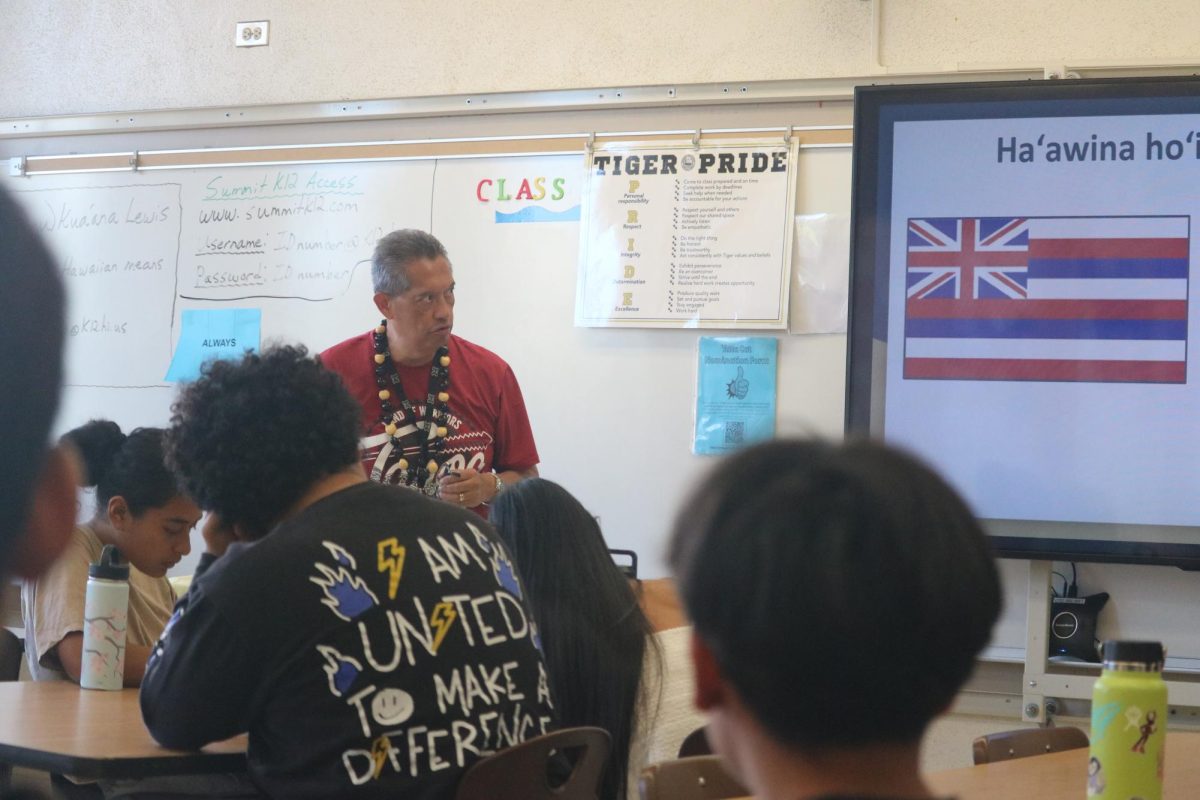

On May 15, Kuhlmeier gave a presentation about her case to a group of passionate publication students. Kuhlmeier was the editor-in-chief of the Hazelwood East High School newspaper in 1983. For one issue of The Spectrum, they decided to cover the problem of teen pregnancy, which was a very widespread issue at the school.

“At any given time there were anywhere from 25 to 40 girls that were pregnant. It was a lot,” Kuhlmeier said.

With a controversial story like that, Kuhlmeier made sure to cover all of her bases. She either removed or changed the names of every pregnant girl that was interviewed and had both the girls and their parents sign off on the article. The issue also included stories covering divorces and runaways. These issues were serious and heavy, but Kuhlmeier and her staff—including reporters Leslie Smart and Leanne Tippett, who joined her in the case against Hazelwood School District—believed that students should have the right to read about things that may affect their daily lives.

“If you are old enough to get pregnant, shouldn’t you be old enough to read about it?” Kuhlmeier said.

Unfortunately for Kuhlmeier and her staff, the school had recently hired a new journalism adviser. This adviser decided to go to Robert Reynolds, Hazelwood East’s principal, for prior review. Reynolds cut the articles from the paper without discussing it with the students or talking to them at all. The next Monday, when the paper came out, the student journalists were livid. Reynolds had decided that the articles were, “too mature for an immature audience,” as Kuhlmeier recalls. He even went as far as to insult Kuhlmeier, Smart, and Tippett, calling the articles “trash.”

The journalist ended up taking this case to the courts, where it eventually reached the Supreme Court in 1987.

The verdict of this case decided on Jan. 13, 1988, is what makes it relevant some 40 years later. The United States Courts stated, “The U.S. Supreme Court held that the principal’s actions did not violate the students’ free speech rights…the school had a legitimate interest in preventing the publication of articles that it deemed inappropriate and that might appear to have the imprimatur of the school.”

Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier resulted in a direct blow to students’ First Amendment rights and the allowance of student censorship is still common law in almost every state. Kuhlmeier, who is still very active in the fight against censoring students and their publications, explained that censorship happens very often. “I can’t give a specific number, but all the time,” she said.

Censorship deeply affects its targets, especially for students. They can spend hours on an important and well-researched story, just for it to be suppressed. In most cases, it’s unfair and unjustifiable. Kuhlmeier knows better than most how heartbreaking censorship can be.

“You can’t give up on something you are so passionate about,” Kuhlmeier said.

Kuhlmeier also explained that censorship often doesn’t come from pure intentions, but rather a fear of students’ voices. She thinks that administrators are intimidated by students’ ability to investigate and report real hard-hitting news. Especially with the rise of social media, which can be a very valuable tool in reporting.

Editor-in-chief of the Ledger and three-year publications student Bryleigh Conley expresses her opinion about the case.

“I think everyone should be able to get their opinion out there, but if you’re just being shut down then [student’s] voices won’t matter,” Conley said.

Luckily for students, many lawyers and activists are fighting to make new laws that will counteract the Hazelwood decision. One of the ways they’re doing this is through the national movement by the name of New Voices. Headed by state-based activists, New Voices’ goal is to protect student press freedom through state laws.

According to the Student Press Law Center, “New Voices laws ensure that student media can only be censored if that media is libelous or slanderous, contains an unwarranted invasion of privacy, violates state or federal law, or incites students to disrupt the orderly operation of a school.” These laws also protect advisors who refuse to censor their students.

So far, 17 states have passed New Voices laws and Missouri has introduced a bill that has passed the House of Representatives but has yet to pass the Senate. Many other states have pending bills, too, including Arizona, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.

The legacy of Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier is one of restriction and mistakes, but it also serves as a lesson for all students, not just those in publications programs.

Lilly Brown, a junior and social media editor, said “[Kuhlmeier] said that you should never allow someone to just tell you no without an explanation and you should always ask why not. When she said this, it made me think of how many times I got cut short because I just allowed someone to tell me no and not ask questions.”

Brown also shared that after hearing Kuhlmeier’s story, she became inspired to cover the hard-hitting issues. The message from Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier is that one never back down from something they truly believe in.

This story was originally published on LHStoday on May 17, 2024.