The Zeller Student Center is crowded with people — a long, bustling line waiting to get lunch and an even longer line waiting to check out. Each day in the servery, hundreds of students and faculty buy their food. Whether it be a morning muffin wrapped in plastic or the chef’s entree on compostable plates, the servery is a campus hotspot. Outside, the trash piles up. There is much to manage in the servery, such as keeping the flow of traffic orderly and getting every person a nutritious meal. At Archer, another priority has emerged in past years: how to make lunch, as well as the rest of the school, more sustainable.

As fears of an increasingly unstable climate grow, many members of the community have continued pushing to make the school a more sustainable campus. Schools are massive energy consumers, but many believe they can be used as a force to combat climate change, rather than remaining complicit in its progression.

Issues Facing Schools

Environmentalism is a multifaceted issue — and by extension, so is the process of making a school effectively environmentally friendly. Sustainability teacher Casey Huff is driving an ongoing process to incorporate sustainable solutions and practices into Archer. She believes schools have not been used to their full potential as resources to combat climate change. Huff added that reforming schools to be climate conscious is an important step in securing a sustainable future.

“Think about how big [American schools’] footprint is,” Huff said. “I mean, they are not only physically occupying large areas of land, but they are utilizing paper in their classrooms. They probably have some sort of food service — so there’s inevitably food waste. There’s inevitably a lot of resources that are coming out of those cafeterias as well.”

Rebecca Grekin, a PhD candidate in Energy Resources Engineering at Stanford University, said that institutions need to acknowledge all levels of emissions they put out – scopes one, two and three.

She said scope one emissions are “direct” — carbon burned on property owned by the institution, such as water heaters or transportation fuel. Scope two emissions are indirect and classify energy that an institution uses but does not produce, such as electricity. Scope three emissions, often the hardest to measure, are emissions an institution indirectly affects on the value chain through what it purchases and produces. Grekin said many schools do not consider their scope one and two emissions, much less scope three, which needs to change.

“We need the integration of sustainability in all of the things that already exist,” Grekin said. “Because that’s how society is going to need to move forward … for us to have a chance of actually doing something before it’s too late.”

Implementing Solutions in Schools

The United States Department of Energy reported in 2022 that schools nationwide emit roughly 72 million metric tons of carbon dioxide a year, nearly three times the amount the city of Los Angeles emitted the same year.

“Schools are a really — unfortunately, just by their sheer size and volume and number of people that schools in the United States are serving — a big contributor to greenhouse gasses,” Huff said. “But I also think that [schools] haven’t been leveraged in ways to be a solution.”

Huff said while she hopes all schools will eventually integrate sustainability into daily life, private schools are in a unique position to decide their budget, curriculum and other programs, a freedom public schools do not have. One major focus of Archer’s sustainability journey is reducing food waste through composting programs in the garden and servery.

CulinArt, the vendor Archer partners with to run the servery, has a policy emphasis on sustainability. Meghan Lambert, CulinArt’s on-campus representative, said the servery is very proud of not having excessive food waste, despite many restrictions on what can be done with leftover food. The servery is not allowed to donate unused meals or ingredients, so the staff often repurpose ingredients any way they can.

“We will add them to something for the salad bar or try to rework them into another menu item just to try to eliminate the waste,” Lambert said.

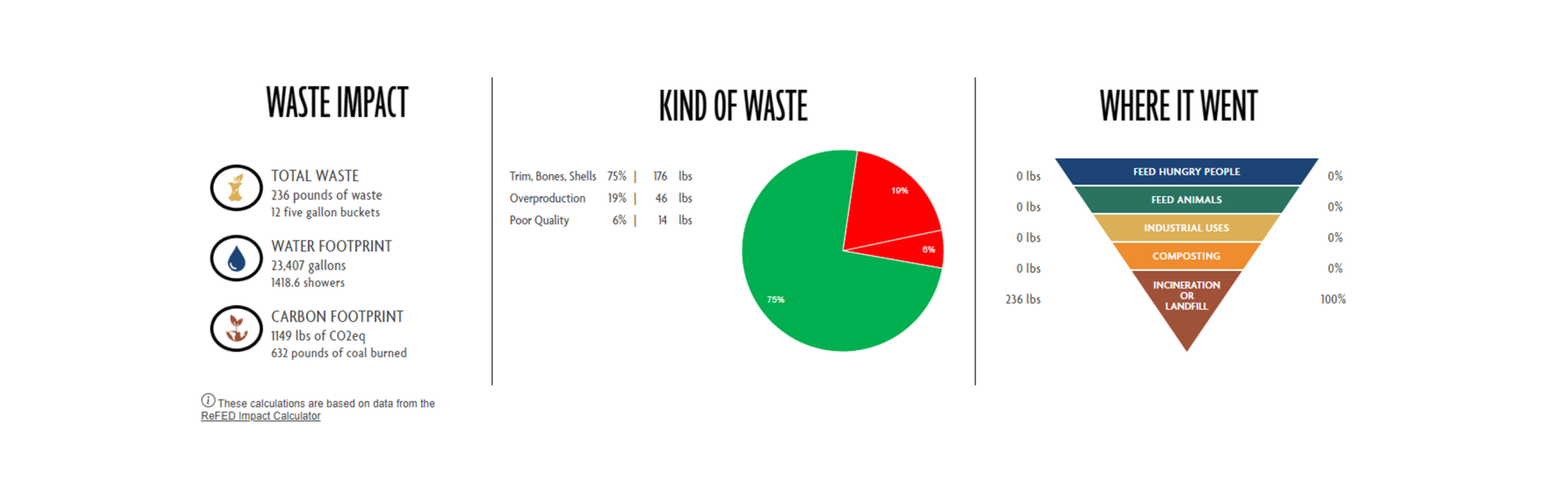

Another feature of the servery that Lambert is proud of is CulinArt’s “Waste Not” program, which measures how much the servery wastes as well as what type of waste it is. “Green waste” is waste considered unavoidable, such as chicken bones or fruit peels, while “red waste” is waste that could have been avoided, such as food that spoils or is wasted in overproduction.

“Anything that is considered food waste in the kitchen … all of that gets tracked and recorded, and we know like what kind of waste it is, too,” Lambert said. “You can use it to learn from mistakes to get even better at reducing food waste.”

Similarly to the servery, Huff said the composting program is constantly changing and becoming more effective. Archer Council for Sustainability Executive Board member Grace Ryan (‘25) said the school recently shifted from aerobic composting in the garden to partnering with Los Angeles City’s anaerobic compost, which has made it possible for them to compost bones, meat scraps and meals containing oil, all of which had previously been off-limits.

“The problem with the [old system] is that we’re not an industrial composting system … it really limits what we can compost,” Ryan said. “[With the new system], we can send more of our trash that would otherwise just go to waste. It can be repurposed and the compost is distributed to local farmers, which is really cool.”

Ryan, Huff and Grekin all acknowledged the stress and fear that can come along with increased awareness of climate change. Grekin said while it can be easy to focus on the negative carbon impacts humans have in the world, it gives her hope to remember the ways people can change the world for the better.

“The idea behind the carbon handprint is that it’s all the impacts you can have outside your own,” Grekin said. “So if I can convince somebody else to also recycle, or somebody else to take the bus, you know, half the times they go to campus or something like that, you can have a larger handprint than your footprint, and so you can be doing net positive for the world in terms of the emissions that you’re avoiding.”

Student Involvement

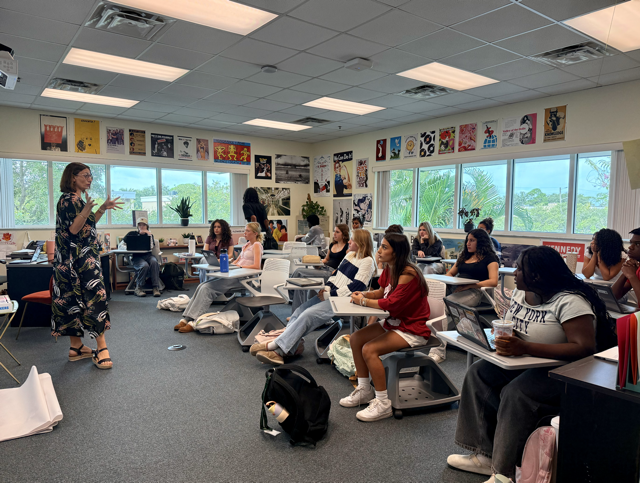

A unique aspect of Archer’s sustainability effort, Huff said, is that students work in tandem with adults to craft a more sustainable future. The Archer Council for Sustainability, who runs the composting program and organizes education around environmental issues, is entirely student-led. Other clubs with sustainable focuses around campus include Ecostitch, Clean Beach Club and Animal Rights Club. Ryan attributes the growing number of students involved in sustainability to Archer’s commitment to integrating sustainability into its curriculum.

“Integrating environmental education into younger grades is something especially prevalent because you need to have this understanding of what’s happening if you’re going to make any change,” Ryan said.

Grekin said educational institutions can compound their positive environmental impact by integrating environmental consciousness into all curricula. She said schools are in a unique position to show people all the ways they can be involved in creating a better future.

“I used to think the only way to do work in sustainability was being a chemical engineer,” Grekin said. “And today, I think that that’s totally wrong. And literally whatever you want to do, if you want to integrate sustainability into it, there’s definitely a need for that and a way to do it.”

This story was originally published on The Oracle on May 19, 2024.

![Senior Dhiya Prasanna examines a bottle of Tylenol. Prasanna has observed data in science labs and in real life. “[I] advise the public not to just look or search for information that supports your argument, but search for information that doesn't support it,” Prasanna said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0073-2-1200x800.jpg)