My father would often ask me “¿Qué estás haciendo? [What are you doing?]” as he walked through the front door after work. Thinking hard on how to respond and using the limited Spanish vocabulary I memorized, my reply would be “Nada [Nothing].”

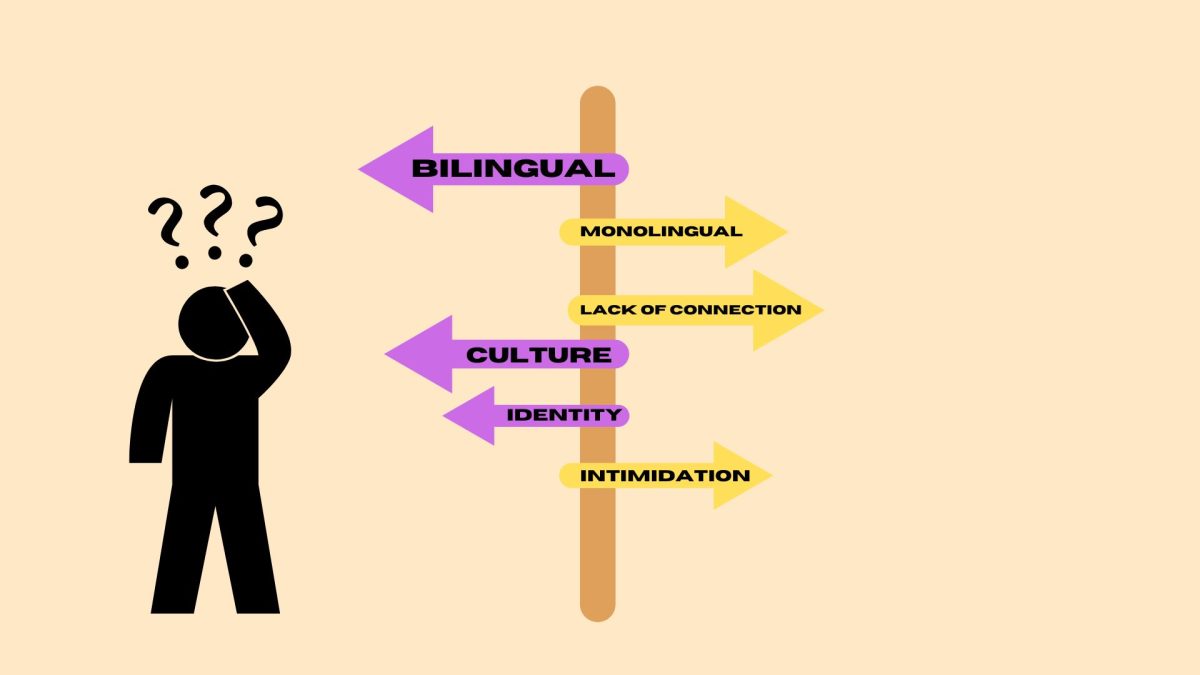

The Spanish I unconsciously picked up from years of listening to him speak to family members never amounted to a full conversation between the two of us. Before I could think of something to add to my one-line responses, he’d switch back to English and my life as a monolingual would go on.

My father is the sole Spanish-speaking parent of our household and I always wondered why he didn’t attempt to teach my brother and myself his native language. While it didn’t bug me when I was younger, now that I’m in college and minoring in Spanish, I can’t help but feel that learning his native tongue earlier would have come in handy.

This lack of language transfer from one generation to the next isn’t a personal problem, but is quite common in a group referred to as “heritage speakers and learners.” Individuals who were exposed to a generational language in a home or school setting, but it’s not their primarily used or understood language, fall under the category.

However, when native tongues aren’t passed down to younger generations, tensions strain as heritage speakers are left physically looking like their culture but not knowing how to interact with it. For languages to pass down each lineage, ancestors must share the burden of teaching for their young to be truly embedded within their respective cultures.

Speaking the same language is the key to identifying with a community that holds like-minded phrases, practices and history. Without this preservation of language, younger generations risk not being a part of this legacy.

San Francisco State University Chinese professor, Yang Xiao-Desai, who specializes in second language acquisition and actively conducts research with heritage speakers, says younger generations place an importance on bilingualism because they are searching for a missing cultural identity.

“It’s like there is a complex emotional connection, an identity,” Xiao-Desai said. “The missing of the heritage language actually creates a generational condition, it’s kind of a generational tension.”

Learning a native tongue can feel like finding the missing piece to a puzzle as it allows one to connect through cultural similarities such as inside jokes and shared experiences.

Raelene Elisan, an SFSU apparel design and merchandising student, identifies as Filipino and Mexican but neither of her parents taught her and her siblings Tagalog or Spanish. Elisan says that not knowing either language has caused her to feel disconnected from herself.

“I would love to be that deep into my culture,” Elisan said. “I think personally in my heart, I would feel more connected if I did know my native language because I do feel a major disconnect in myself right now. That probably is an aspect of why I’m so disconnected with myself and my culture.”

I’ve often silently judged my dad for not providing this exposure to his native language.

When I asked why he didn’t teach my brother and I Spanish, my dad said it didn’t seem necessary at the time. For other parents, the lack of teaching comes from a place of protection.

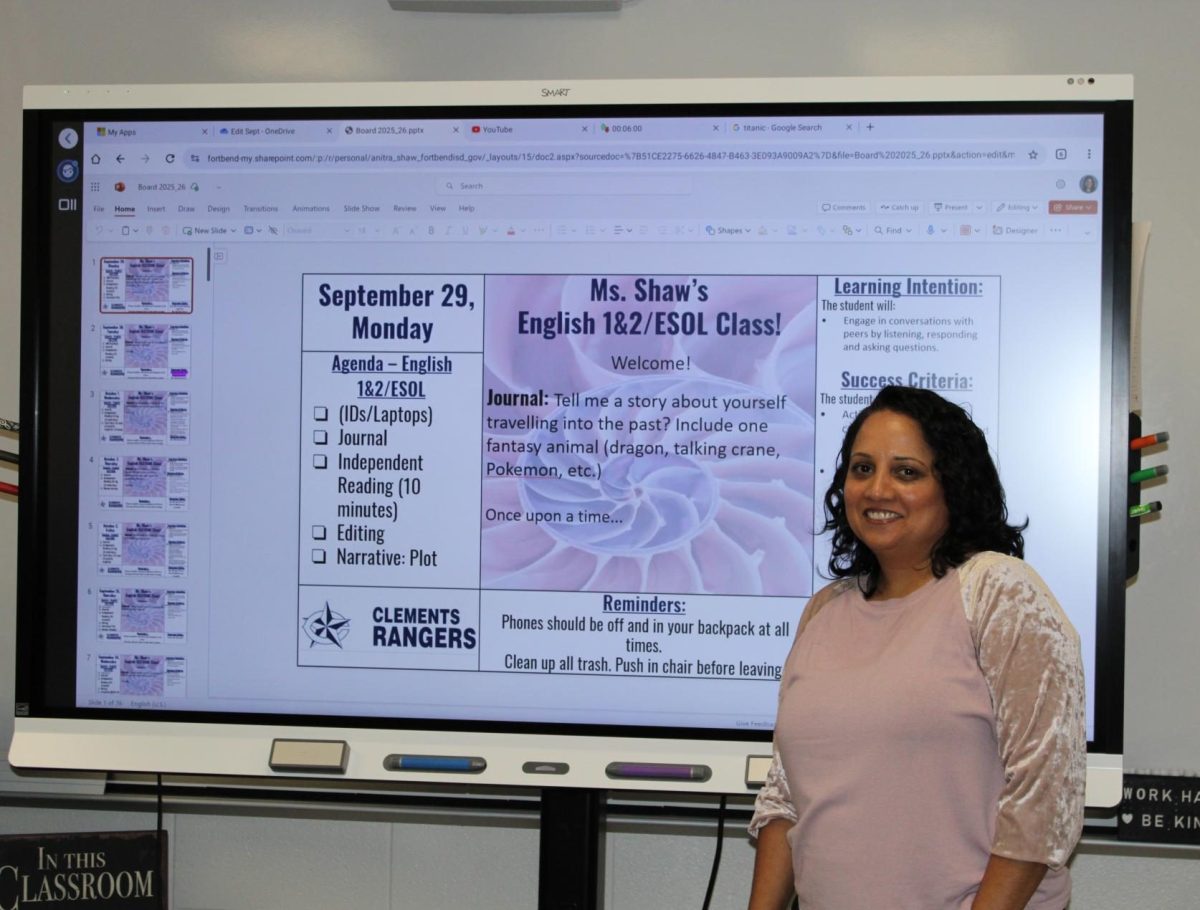

Ana Luengo, SFSU Spanish program coordinator and professor, said that parents who are dominant in another language will refrain from teaching their children as a defense strategy against discrimination.

“[Parents] have also had some experiences with discrimination and that’s pretty painful,” Luengo said. “They don’t want kids to have the same experience. So they want their kids to be fluent in the other language in order to be really integrated.”

This fluency in English is believed to give the younger generation an easier passage into society. Without bilingualism, heritage speakers are able to merge into mainstream society sooner rather than later, according to Xiao-Desai.

In a 2019 Census Bureau study, data showed that the “number of people who spoke only English also increased, growing by approximately one-fourth from 187.2 million in 1980 to 241 million in 2019.”

One possible reason for this growth is that younger generations and individuals may choose to speak only English to avoid teasing and to blend in with their peers.

Danie Valdivieso, a SFSU theater student, grew up in a Spanish-speaking household and although her first language was Spanish, entering school caused her to feel like she needed to change herself.

“You feel like you need to change who you are and what you look like and also talk like the school system,” Valdivieso said. “I stopped speaking Spanish when I was like 11 and started responding to [my family] in English. They would speak to me in Spanish and I would respond in English.”

Looking back, Valdivieso said she regrets cutting out Spanish from her repertoire because she’s realized its value in speaking with others at work and in school environments.

“I was in the service industry for almost a decade and a lot of the people behind the line, a lot of people cooking, speak Spanish,” Valdivieso said. “I had to make an effort to communicate because I wanted to respect them. I want to get myself back to my culture.”

In an attempt to relearn native languages or learn them for the first time, younger generations also experience a form of discrimination coming from home.

Elisan said in her attempt to learn Spanish, her efforts were shut down and her accent came off as too Americanized for the members of her family that did speak the language.

“It was like if I didn’t make the effort, I was fine and if I did make the effort, then I was bullied,” Elisan said. “So then I was like, ‘it’s OK ,’ I’m just going to be at peace with not knowing myself culturally. But don’t judge me for not knowing Spanish. That’s not my fault. That’s what made me mad.”

Admittedly, monolingualism can also be valuable in the sense that individuals feel less pressured to keep up with another language.

Presley Takapu, an SFSU marketing student, grew up speaking only English but has family who speak Tongan. Although she wishes she would have learned Tongan for communication’s sake, Takapu said because the language isn’t widely used in the U.S., it wouldn’t have been as beneficial in some environments as others.

“I think it just depends on, like, the job opportunities too,” she said. “Depending on what language, a lot of [employers] look for certain languages. So if you’re of a smaller dialect, it doesn’t have that much of an impact on if you get the job or not.”

With this reasoning, Takapu said she is content with only knowing a single, yet universal language.

“I’m glad that I’m fluent in English since English is used all around the world,” Takapu said. “So I feel like it’s a very stable language. So, I mean, I’m not mad that I’m not bilingual.”

From a practical standpoint, focusing on a single language can also reduce the time and effort required for teaching and learning. For Elisan, one of the reasons Spanish wasn’t taught in her household was because her single mother was busy taking care of six children.

“None of us know Spanish,” she said. “[My mother was] too busy and she wasn’t always at the house. And then when we’re home, it’s more like you raise yourself as your parents are busy.”

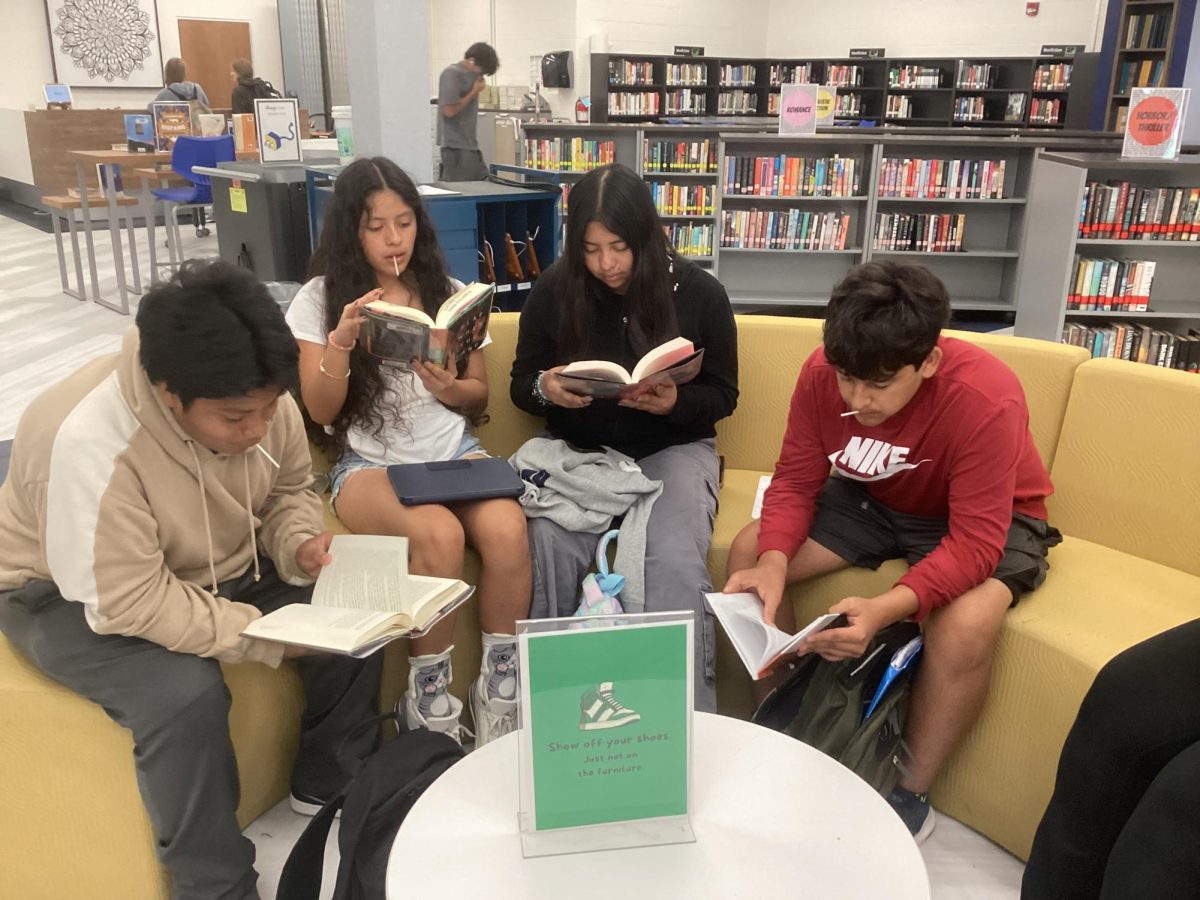

Although some households carry an underappreciation or lack sufficient time for learning native languages, modern society has gained a new admiration. Xiao-Desai said bilingualism was formerly looked down upon by schools and parents because they believed it had a negative connotation to learning.

“There was a perception from the ‘70s and ‘80s before science and linguistics research became very robust, that if I expose two languages, I’ll confuse my children,” Xiao-Desai said. “If children are exposed to two languages, then they will cognitively develop slower.”

In comparison, Xiao-Desai said that modern-day technology and research proves learning and speaking another language has “cognitive benefits” in performance of other subjects.

According to a study on neurological differences between monolinguals and bilinguals by the National Library of Medicine, they found that various levels of bilingual learners “show increased grey matter in areas involved in verbal fluency tasks.” Grey matter is a tissue in the brain that contributes to cognitive function including memory and learning.

Additionally, Luengo said that acquiring languages can make you more valuable in a career, benefit your neurological flexibility and contribute to a further multicultural population.

“When we know more languages, we have more areas of our brain working,” Luengo said. “You can read more books and you can understand more songs and you can watch more movies in the language. But from a very human perspective, you can connect with more people because you are understanding the world from another perspective.”

While learning Spanish not only for my minor but also for my culture, I have not been able to contribute to this diverse purpose.

Communication with another culture, even if it’s one you belong to, is intimidating when you are focused on getting the grammar and conjugations correct. And rather than speak to a real person, I have hidden behind a screen of Duolingo and textbook examples.

Instead of hyperfixating on verbs and pronunciation, Luengo said learning a generational language and any for that matter relies on real connections. Without interpersonal relationships, learning a generational language is nothing but a gold star.

“It’s very important to learn languages in communicative environments and not just as a product, because languages are not products,” Luengo said. “There are a lot of things involved in languages like feelings, the music of language, and it makes a more grounded person.”

This story was originally published on GoldenGateXpress on September 18, 2024.