Former president Donald Trump will exit the presidential race, citing non-specific personal reasons. This social media announcement comes just less than a month before the presidential election on Nov. 5, leaving the Republican party with little time to find another presidential candidate.

How long did it take before you realized what’s written above is completely false? Misinformation — declared the number one threat to democratic processes by the World Economic Forum — contributes to civil unrest, distrust of governments and polarization of communities across the globe.

“When it comes to policy-making, these are things that can impact thousands or millions of people’s lives for many, many years,” Stephen Prochaska (he/him), a researcher at the Center for an Informed Public at the University of Washington, said. “So, when you make a policy decision based off of misinformation, you’re actually harming the constituents that the person or representative should be trying to help.”

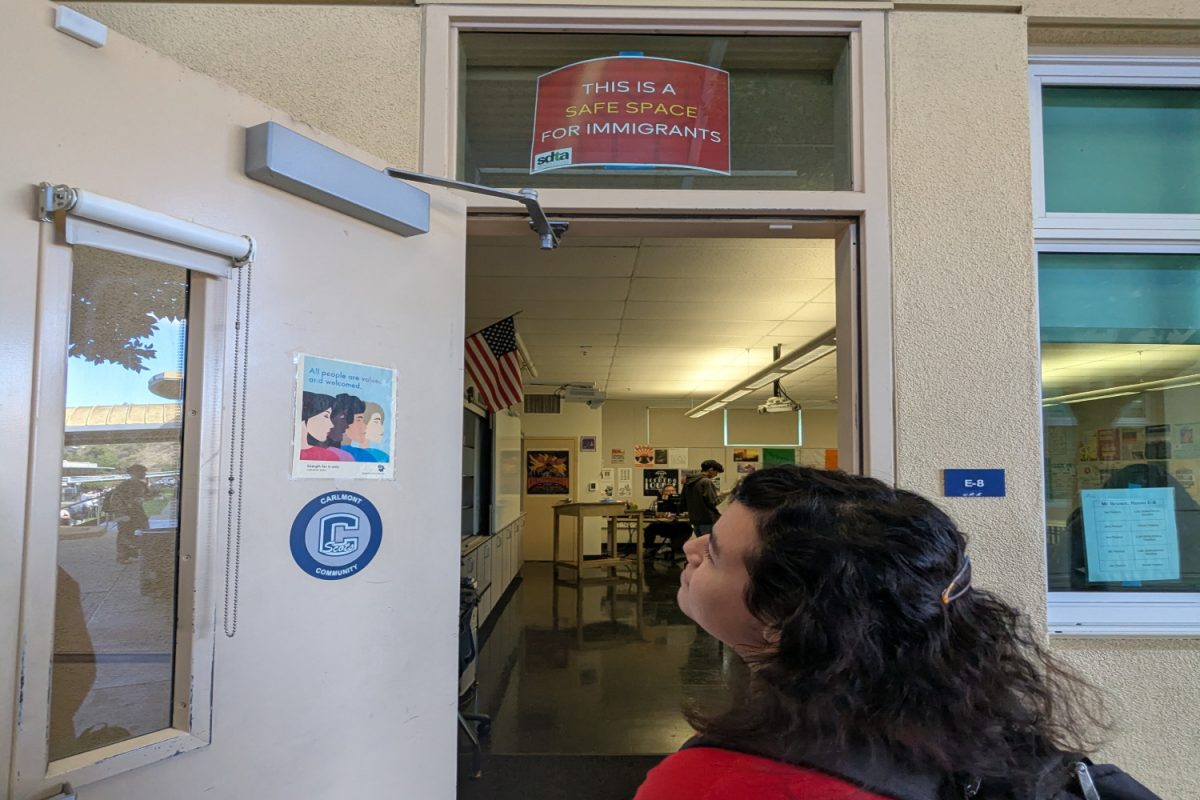

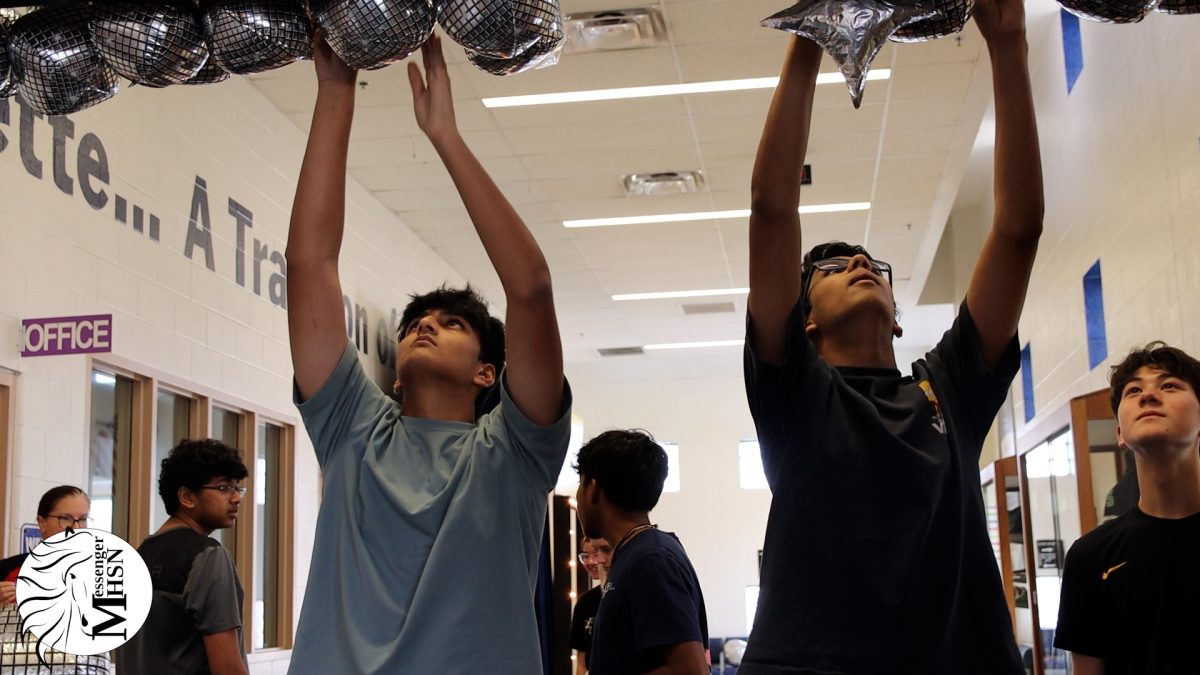

A recent example of misinformation is the rumored story of Haitian immigrants eating local pets in the town of Springfield, Ohio. The story surfaced in early September when a Springfield local claimed on her Facebook page that Haitian immigrants were stealing and consuming neighborhood pets. The story went viral on social media after far-right groups spread it across platforms like Facebook and X, formerly Twitter, before being proven false by Springfield police. However, damage to the community had already been done, with over 33 bomb threats made to schools throughout Springfield that prompted city-wide closures. Junior Rylan Cranmore (he/him) said he believes social media platforms are especially susceptible to misinformation due to a lack of moderation, allowing it to quickly snowball.

“Most people are not political scholars, and they don’t know what they’re talking about,” Cranmore said. “And so they’ll say something, and then their buddy says it, and then another buddy says it, and then eventually, a bunch of people believe something that might just not be true.”

The Springfield rumor entered mainstream media when former president Donald Trump mentioned it during the ABC presidential debate, which was viewed by over 67 million people. Prochaska said that when major political figures repeat misinformation, there’s a major impact on public perception due to how these figures engage with “deep stories,” which are underlying beliefs that often change interpretations of modern events.

“What they’re doing is they’re keying into specific pieces of these ‘deep stories’ to clue in their audience how to interpret a particular event,” Prochaska said, going on to use election fraud as an example. “To say, ‘Oh, this is actually evidence of this ongoing election fraud that we’ve been claiming this whole time,’ even when it’s not actually. But (Trump’s) in the audience and tells them how they need to react, and then they’ll kind of take it from there.”

Political figures may also take moments out of context — another form of misinformation — in an attempt to gain an advantage over competitors. News organizations have recently criticized Vice President Kamala Harris’s “official rapid response” Instagram account, KamalaHQ, over a misleading post that asserted Trump forgot which state he was in while at a Pennsylvania rally. The post referenced a moment when he referred to the crowd as “North Carolina,” but in context it’s clear Trump was referring to a specific individual in the crowd who was from North Carolina.

Misinformation has led to disaster, both in the presidential election and outside of it. In early October, false claims spread across social media platforms that the Federal Emergency Management Agency withheld aid from Republican areas in the wake of Hurricane Helene. Prominent figures in the Republican party have echoed these claims. Misinformation has been a force in previous presidential elections as well.

During the 2020 election, conservative voters in Arizona noticed that the Sharpies distributed to them bled through the ballot paper. After Biden won the state, stories began to appear online that the Sharpies were given to Republican voters so that their ballot could not be read by the counting machines and their vote therefore would not be counted. Prochaska said that this event was exacerbated when in-person voters saw that their mail-in ballot had been canceled online, then jumped to the conclusion that their vote had been thrown out altogether.

“That reinforces their belief,” Prochaska said, referring to the Sharpie incident in 2020. “It reinforces the belief of their community, and it becomes this cycle where they continuously generate and share this evidence that is actually not evidence of their pre-existing belief, but that pre existing belief often leads them to perceive it as evidence.”

Prochaska refers to this as collective sense-making. When a group is presented with an ambiguous situation, someone will present a possible solution. No matter how outlandish the idea might be, it will gain momentum as it is repeated and embellished by members of the community. Echo chambers are one mechanism by which collective sense-making occurs, and they magnify political polarization, where groups with contrasting opinions or beliefs are increasingly divided.

In recent years, Americans have been moving away from centrist views to political extremes. According to the Pew Research Center, from 1971-2022, House and Senate Democrats’ views have become 7% and 6% more liberal respectively. From 1971-2022, House and Senate Republicans’ views have become 25% and 28% more conservative, respectively. This polarization can make political discussion difficult and makes it hard for Congress to pass legislation due to partisan gridlock.

“It polarizes the American people, which is a major issue,” Cranmore said. “And just as social media does, like the insurrection on Jan. 6 made people very, very angry, and angry people aren’t very nice people. They don’t like to listen to what the other side thinks, and that just further increases the divide between the two political parties.”

According to a Pew Research Center survey, 55% of adults say they often feel angry about politics. Senior Lucas Pearce (he/him) said a heated discussion about abortion laws in his civics class forced his teacher to intervene and steer students away from that topic.

“When people feel like their beliefs are being attacked, they’re going to respond a way that they feel the need to defend it, especially when it’s core to who they are,” Pearce said.

There are ways to defend against misinformation and polarization. Prebunking, for example, approaches misinformation like a virus, exposing people to information they know to be false to make it easier to spot. Prochaska said misinformation can also be fought on the individual level with something as simple as a conversation.

“It can start with your friends and family,” Prochaska said. “Just starting with them and having genuine, empathetic conversations: not combative, not defensive, just letting them speak.”

This story was originally published on Nordic News on October 28, 2024.