The tornado wasn’t something they could see ahead of time.

Sure, NBC5 Chief Meteorologist Rick Mitchell remembers that he’d forecasted thunderstorms developing west of Tarrant County. But that was a Level 2 risk for severe weather. Just north of Dallas County, extending from Denton and farther north into Oklahoma and Arkansas was a level three—enhanced risk—and was where he thought the brunt of the really bad storms would be. Dallas County was just on the edge of that storm.

No sign of a tornado.

And when those storms started developing that afternoon and started becoming severe—with the potential to produce 60 MPH winds or quarter-size hail, Mitchell wasn’t surprised.

WFAA Meteorologist Kyle Roberts wasn’t surprised either. That morning, he’d worked the Sunday morning shift and knew there was potential for severe storms later that day. But he chose to drive back home to McKinney. If the storms did start becoming severe, he decided he would play it by ear and see what he could do to help get the word out from home.

No sign of a tornado.

But as soon as those storms crossed into Dallas County—everything changed.

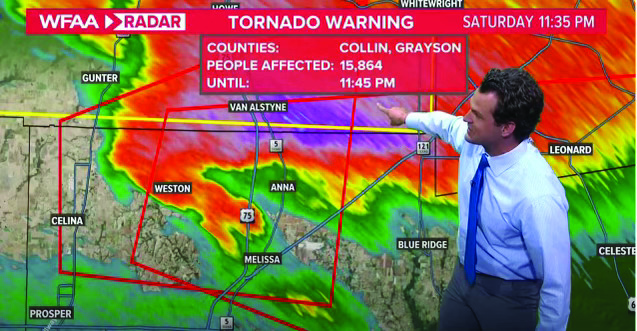

One of the storms developed a signature on the radar—a storm that had the capability of producing a tornado.

And minutes later—one touched down.

“These storms went from, ‘Yes, there are severe storms,’ to, ‘Oh my God, it’s producing a tornado!’ in a matter of maybe 10 minutes,” Mitchell said.

When Roberts saw the storms blowing up and realized the ones in North Dallas were going to be significant—he was stuck between a rock and a hard place. It would take 30 minutes to get down to the station. If he wanted to leave—he’d have to leave quick, then and there. The storm was on its way, and he would have to head straight down US75 and try to beat the worst of it.

He ultimately chose to wait it out. Getting the word out on social media was his main priority at that point — and he could do that from home.

But as soon as those storms crossed US75, he jumped in his car and raced down to the station.

He knew it was a pretty significant tornado—he could see that on the radar. He could see the damage occurring as it moved through North Dallas. But driving down the highway, he didn’t know what he was going to run into.

Just south of 635, crossing Royal, the highway—usually so well-lit by those high-mast lights—was pitch-black. The Home Depot storefront—obliterated. He had to slow down a bit to maneuver across the all the debris everywhere on the highway—the insulation, metal, tree branches.

But he saw no one stuck on the road or anyone hurt. So he kept driving downtown.

At the station, they began wall-to-wall coverage. No breaks. No planned programming. Just straight, non-stop information.

WFAA Meteorologist Jesse Hawila and Roberts began alternating being on TV— and whoever wasn’t on TV was helping get the word out on social media and talking with the anchors, producers, and any crews that were out in the field.

It takes a lot of collaboration to do wall-to-wall coverage on severe weather. The person on TV doesn’t necessarily get the information as quickly as the people behind the scenes — so there’s a lot of back and forth between the meteorologists on and off TV.

A lot of, “Hey, what’s the latest Kyle? What’s the latest Jesse?”

And a lot of, “Hey, we just got a report of this,” from offstage.

It was a late night.

Several weeks or months after the tornado, Mitchell met with the National Weather Service because they had access to data that he didn’t have.

With data from the weather instruments on some Southwest planes as they took off from Love Field, it showed that the conditions in Dallas County were much more favorable for tornadoes at the time. There was more wind shear which led to spin in the atmosphere — and it took those marginally severe storms and ramped them up to the point where they produced an EF3 tornado.

“It was almost like the storms were just waiting to get into Dallas County,” Mitchell said.

For Mitchell, it shows how quickly something can change in the span of 30 miles. And, for him, it’s one of the mystifying things of meteorology — that the conditions were so favorable in Dallas County. It was there. And it was gone.

This story was originally published on ReMarker on October 24, 2024.