Autumn is a time of change.

Trees lose their foliage; days shorten; temperatures drop and frost creeps over lawns and roofs. School becomes routine as progress reports go home and the rotating cycle of homework, projects, and tests regains a feeling of normalcy.

But every four years, fall is about more than vibrant leaves and houses decorated for Halloween.

It’s also election season.

At La Salle, that’s felt keenly by seniors, many of whom will be voting for the first time.

“I’m a little nervous, but I’m also just super excited. I’ve definitely been waiting for this for a while,” said senior Madeline Wisler, who is eighteen and a registered voter. “To be able to vote in high school is super cool.”

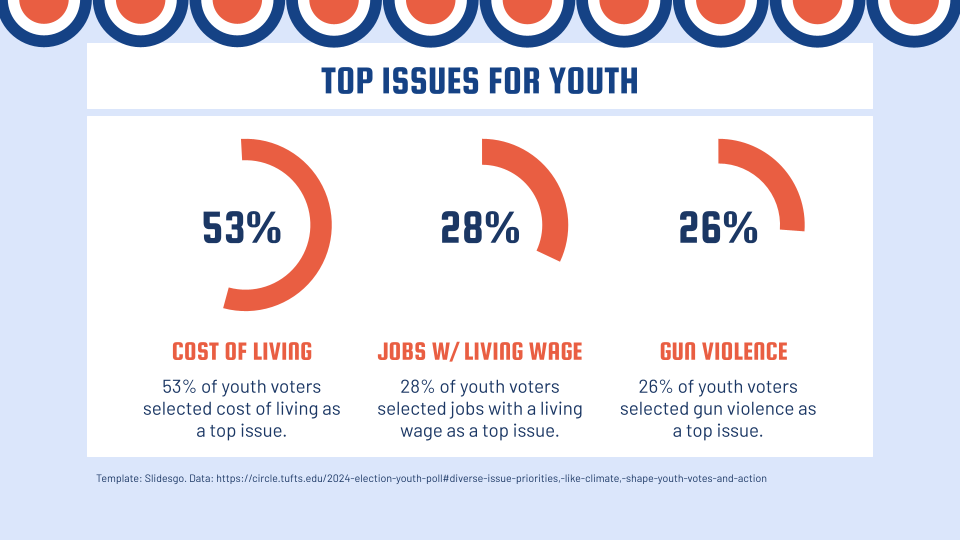

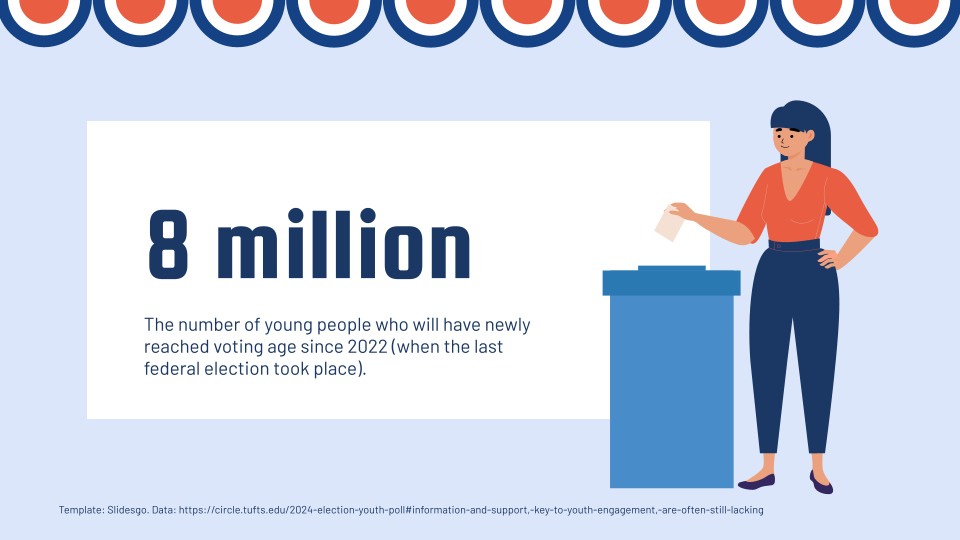

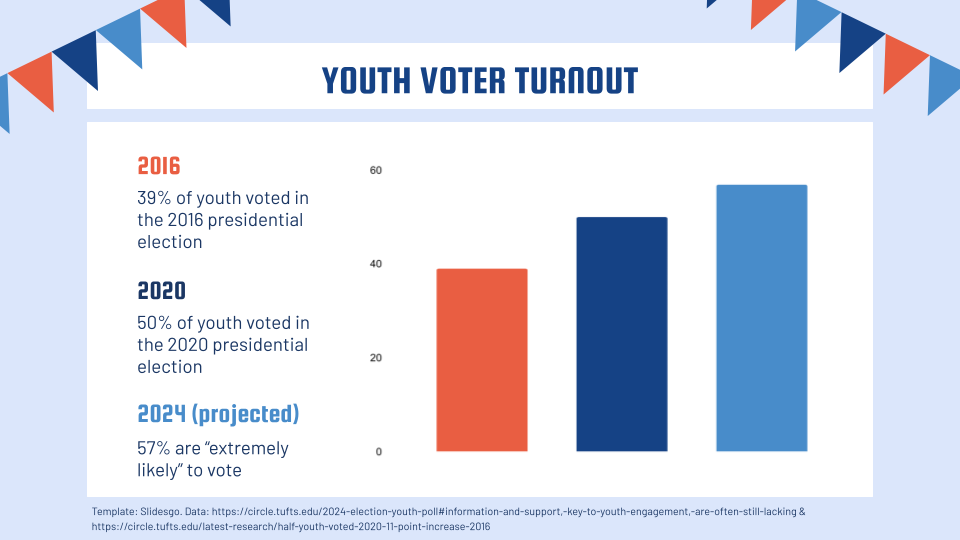

With approximately 57% of youth voters, ages 18-24, saying that they are extremely likely to vote, the turnout of young people at ballot boxes will play an important role in the outcome of this election. However, in 2022, only 49% of citizens 18 to 24 were registered to vote, contrasting starkly with the 78% of 65 to 74-year-olds who were registered voters.

This, Wisler explained, is a problem.

While young people are often the most outspoken regarding issues they care about, they’re not always politically active, something that Wisler finds especially concerning considering that young people are the ones who will live with the consequences or benefits of political decisions the longest.

“I’ll be able to vote for the longest time, and… it’ll have the most effect on me,” she said. “It’s cliche, but it is our future.”

However, underclassmen and students who cannot yet vote also recognize the ripple effects of the election and how it could affect their lives after.

“This is going to be one of the most consequential elections of our lifetime,” junior David Sharyan said. “I just sit and think about it, and I’m just like, ‘when is this going to be over? When are we going to know the results?’”

For some students, that anticipation feels like it has been building for so long it’s reached a boiling point, counselor Mr. Kevin Doyle explained. It’s a constant, in their face reminder, from both the news cycle and social media, about the stakes of this election.

“It seems like this whole thing has been going on forever,” Mr. Doyle said. “Yes, we’re close to the election. But it’s also like, we’ve been talking about the election for months.”

Mr. Doyle said that election fatigue is likely part of the reason that students are not as engaged as he expected.

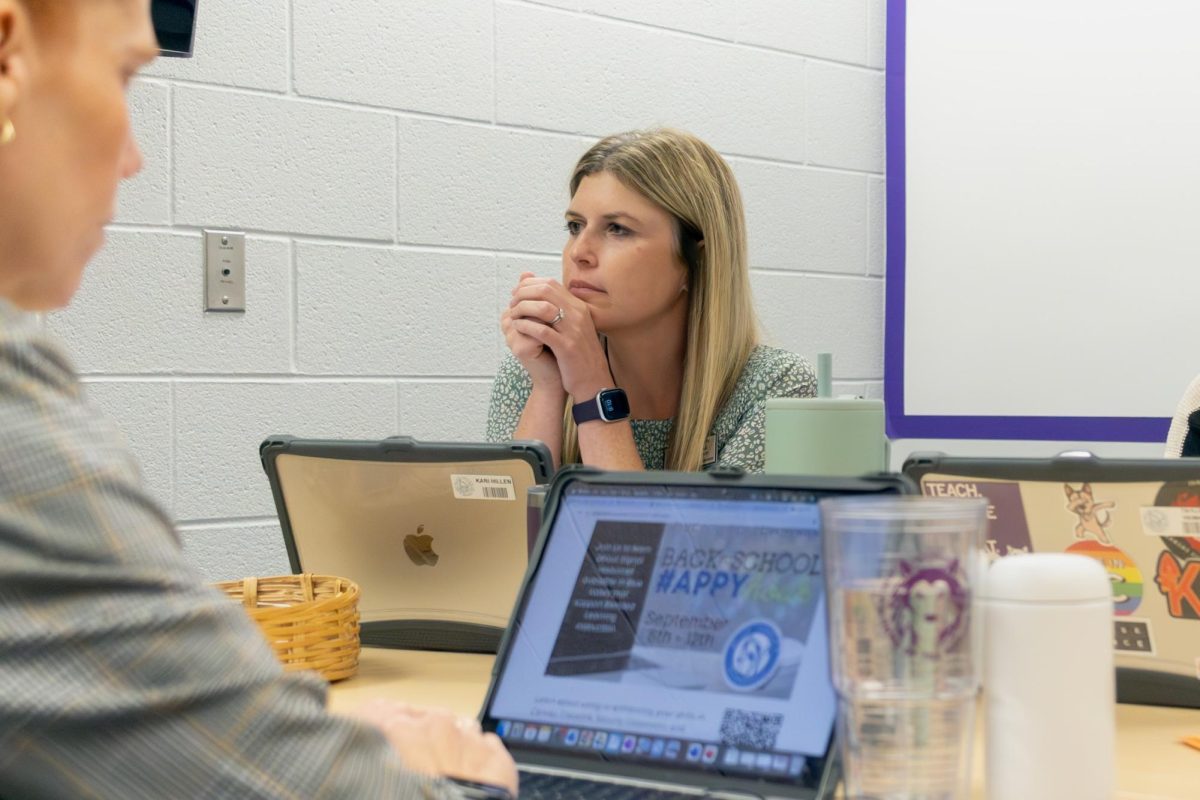

As Social Studies Department Chair Mr. Alex Lanaghan explained, much of the past 12 years has felt similar to a political “holding pattern,” lacking new, different candidates or discussion, which can be frustrating for youth. In part because of that election exhaustion, counselor Ms. Michelle Berry explained that being a little disengaged from the election cycle can be healthier for some students, especially those feeling overwhelmed or hopeless because they cannot vote.

According to Pew Research Center, the politically engaged are the most exhausted and angry, with 72% of those highly engaged feeling fatigued by politics always or often.

For students, Ms. Berry said, it’s important that they balance being informed about the election cycle with their mental health, understanding the line between staying engaged and sacrificing their time to stress and anxiety.

However, she thinks that overall, it’s not good to be disengaged from current political events, as she believes that having civically involved students is imperative in helping them to be educated, informed members of American society.

“It’s normal to have some fear and anxiety about what’s going to happen,” Ms. Berry said, adding that it’s also “important for us to be good citizens and to be engaged and know what’s going on in the world.”

Mr. Lanaghan said that it’s important for students to be able to step back if they are extremely anxious about the election, sharing that he does that himself when getting sucked into political spirals or negativity.

“It’s not all or nothing,” he said. “Moderation is key.”

Social studies teacher Mr. Peter Snow pointed out that while staying up to date about political issues may cause students stress, ignorance of them can have the same effect, as bills could be passed or court cases ruled on that directly affect their life without their knowledge.

“I understand why people are kind of turned off, but nevertheless, it’s still important to note because it’s going to shape what happens to them,” he said. “There’s ways to manage this so that it’s not an all-consuming doom and gloom.”

Balancing that is crucial, sophomore Daniel Garbitelli expressed. But it’s hard to do.

Garbitelli, a member of the Speech & Debate team, explained that he regularly checks the news to do well in debate, which requires foundational knowledge of current events. Between that and discussing politics with his parents and some of his friends, he considers himself fairly up-to-date with the election cycle so far.

Still, the intense polarization around this topic has made political discussion with his peers extremely difficult.

While Americans are not as ideologically polarized as they believe themselves to be, affective polarization — also known as emotional polarization — is growing, increasing the personal investment of citizens in political leaders and their unwillingness to hear opposing perspectives. Cancel culture has also deepened political divides, as people don’t want to be ostracized if the political views they express fall outside the norm of their community.

According to Garbitelli, the impact of that split at La Salle is both good and bad.

“On one hand, people shouldn’t be scared of saying their political views,” he said. “On the other hand, if everyone shared their political views, it would lead to a lot of tension between students.”

Junior Gabrielle Jones echoed this, sharing that polarization has deeply affected students’ willingness to converse about the upcoming election.

“It’s us or them,” Jones said. “There’s no interconnection like how it used to be in elections, where you could discuss and publicly debate without there being any real heated tension and strong dislike for the other party — not just their values, but them as people.”

The move towards character-based discussion of candidates, rather than focusing on their policies, is a problematic shift, Jones argued. As Sharyan explained, prioritizing a candidate’s temperament over their political values can lead to conflict, exacerbating identity politics and sparking hateful, malicious campaign ads and strategy.

Factors such as a person’s race, background, or personality should not be influencing the election, he expressed.

“The person running for president, they are a human,” Sharyan said. “You should never attack the person; you attack the policy.”

Sharyan argued that America seems a lot more divided than it is, proposing that the silence around the election among students was due to people simply minding their own business rather than partisan divides.

But both he and Jones agreed: there’s not enough conversation about it.

“People aren’t willing to talk,” Jones said. “They’re not open to other people’s opinions.”

Jones thinks that although the absence of in-depth conversations or debates is understandable, as it would create more communal division than civic-mindedness, young people need to be more educated about the political process so that they have the information necessary to fully participate in civic life.

That’s where social studies classes come in.

“I always tell the student that everything we’re learning about in class happens in real life,” Mr. Lanaghan said. “Election seasons provide that much more kind of fuel for that argument.”

According to Mr. Lanaghan, across the social studies department, teachers strive to connect class material to current events. They work to ensure that — particularly in senior year Government and AP Government classes — students have the fundamental understanding of the American political system imperative to filtering through misinformation and disinformation, and recognizing whether or not those in places of power can deliver what they are promising.

Presidential elections provide a particularly powerful way to do that, Mr. Langhan said.

While this election cycle hasn’t altered the material covered at all, the order has been a little bit different, Mr. Snow explained. For example, topics such as campaigning have been covered earlier in the year so that they have maximum relevance.

Politics are discussed more in senior-level courses, but Mr. Lanaghan argued that — across grade levels — the election is relevant to the entire student body, as they will all be able to vote eventually.

“In the grand scheme of things, it’s all going to be very real for students much sooner than later, even if it’s only a couple years away versus a couple months,” Mr. Lanaghan said. “It’s not that far away.”

From Mr. Snow’s perspective, every election should be pertinent to the student body, and apathy towards the presidential election signifies the state of our political system and attention spans, illustrating how conversations around it lean towards emphasizing difference rather than the commonalities between our identities and goals.

On top of that, he explained that it’s hard for young voters to see the impact their choices can have.

According to Harvard psychology professor Daniel Gilbert, people are wired for short-term thinking. Human brains are adapted to respond to immediate threats, such as a fire, exam, or wild animal, but miss more gradual warning signs, meaning that issues like climate change can be perceived as less detrimental because it’s difficult to connect them to day-to-day life.

The long, slow ripple effects of youths’ choices at the ballot box may not manifest for ten or 20 years, Mr. Lanaghan and Mr. Snow explained, and in order for students to be civically engaged, teachers need to explain to them the importance of their voting decisions, helping them build it as a habit.

“At La Salle, we talk about creating lifelong learners,” Mr. Lanaghan said. “I want to create lifelong voters.”

For senior Charlie Lewy, the importance of politics and civic life didn’t register until he turned 18.

Although he was previously not tuned into election cycles, that has shifted dramatically since becoming a voter, as now he has an active, direct way to influence political issues — issues that will shape his life even more as an adult.

Both Wisler and Lewy explained that staying engaged as a voter is one of their top priorities.

“When you don’t pay attention, how can you make a good decision?” Lewy said.

Lewy expressed that he mainly evaluates candidate’s values when considering who to vote for, while Wisler’s areas of focus are their behavior and past decision making, as she views how they have carried themselves in the past as an indication of what steps they might take once in the Oval Office.

“Obviously people can change,” Wisler said. “But I think that when a candidate has consistently made similar decisions, the likelihood of them continuing to make those decisions in a presidency is pretty high.”

Wisler feels strongly about the significance of each vote cast, a point of view greatly appreciated by Mr. Langhan.

“It breaks my heart when I hear students say ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter’ or ‘Oh, I’m not going to vote.’ Why? Why would you not do that?” he said. “Every election matters. Every vote matters.”

However, from Sharyan’s perspective, the presidential election is not what will have the most impact on his life.

“My eye, honestly, is on local elections because that’s what’s going to be affecting me, my family, my community, my school,” he said. “Our president is important, but I wouldn’t say that it’s more important than our local elected leaders.”

The head intern for Representative Lori Chavez-Deremer’s reelection campaign, Sharyan has personal experience with the significance of locally elected leaders. As this race — for Oregon’s 5th congressional district, where La Salle is located — is one of the closest watched in the country, it exemplifies the important role teens under 18 can play in elections, Sharyan said, as he has knocked on around 600 doors, and made hundreds of phone calls in the past six months.

“I would encourage everyone to get out there [and] make a difference in your community,” Sharyan said. “You might be that one person who swings that vote, who makes that difference, who truly changes the course of an election.”

With less than a week until the election, Mr. Lanaghan’s advice is clear: have perspective.

“It’s going to be okay either way, right? The world will still go on,” he said. “It should unite us [as] something we get to partake in every four years that we shouldn’t take for granted.”

Both Mr. Snow and Mr. Lanaghan reiterated how crucial it is for students to remain checked-in with the election cycle, even as it comes to a close, and that it’s never too late to start learning about it, either through the media, teachers, or holding a watch party on election day.

It can be as simple as not changing the radio when the news is on in the car, Mr. Snow expressed.

Garbitelli, as an underclassman, said that while the results will be important — and that students should stay engaged with them — they won’t cause any monumental shifts in his life.

“There’s some merit to the idea of ‘what happens, happens,’” he said. “I’m just going to live my life as I’ve lived it.”

That perspective was echoed by senior Phoebe Sandholm, who will not be eligible to vote in the upcoming election.

“It’s important, but it’s not the most important thing in my life right now,” Sandholm said.

Despite being somewhat stressed about the election, Wisler said she is mainly excited, and encouraged other seniors who are 18 to fill out their ballots. Her enthusiasm was mirrored by Mr. Lanaghan.

“Treat it like it’s the Super Bowl, and make it fun, right?” he said. “Get some snacks and watch our democracy in action.”

This story was originally published on The La Salle Falconer on October 30, 2024.