**Editor’s Note: The Jets Flyover Editorial Board has chosen to keep ‘J,’ a victim of deepfake sex crimes, anonymous following consultation with legal counsel, in order to protect the victim. All references are marked with an asterisk.

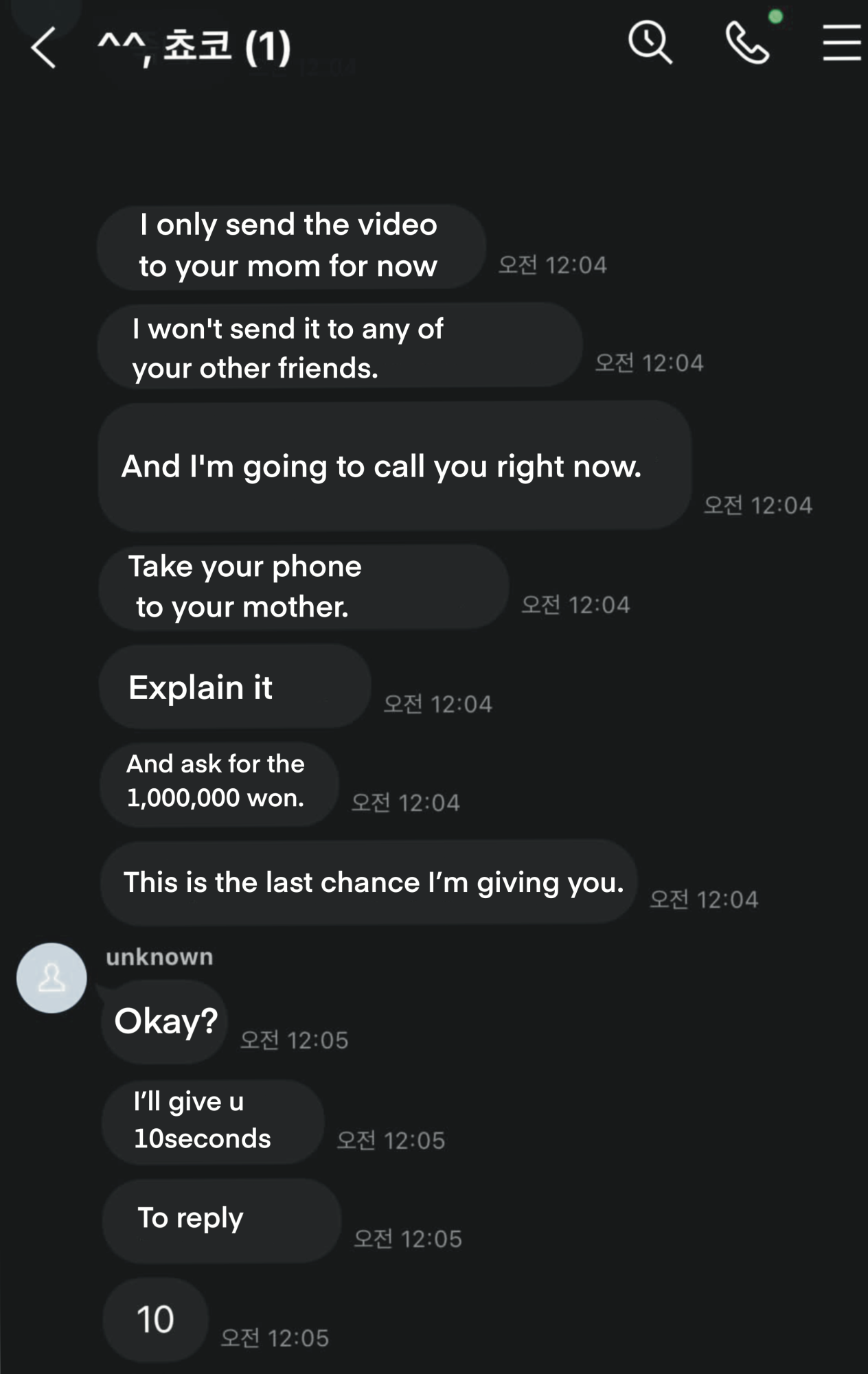

‘J’*, a junior at a local private high school, opens his phone to a graphic video of himself naked in a pornographic video. The message that comes with it reads, “I’ll only send it to your mom right now, not your friends. I’m going to call you, so explain this situation to your mom and ask for a million won ($1000). This is the last chance I’m giving you before I send it to everyone you know.” He can do nothing but tremble.

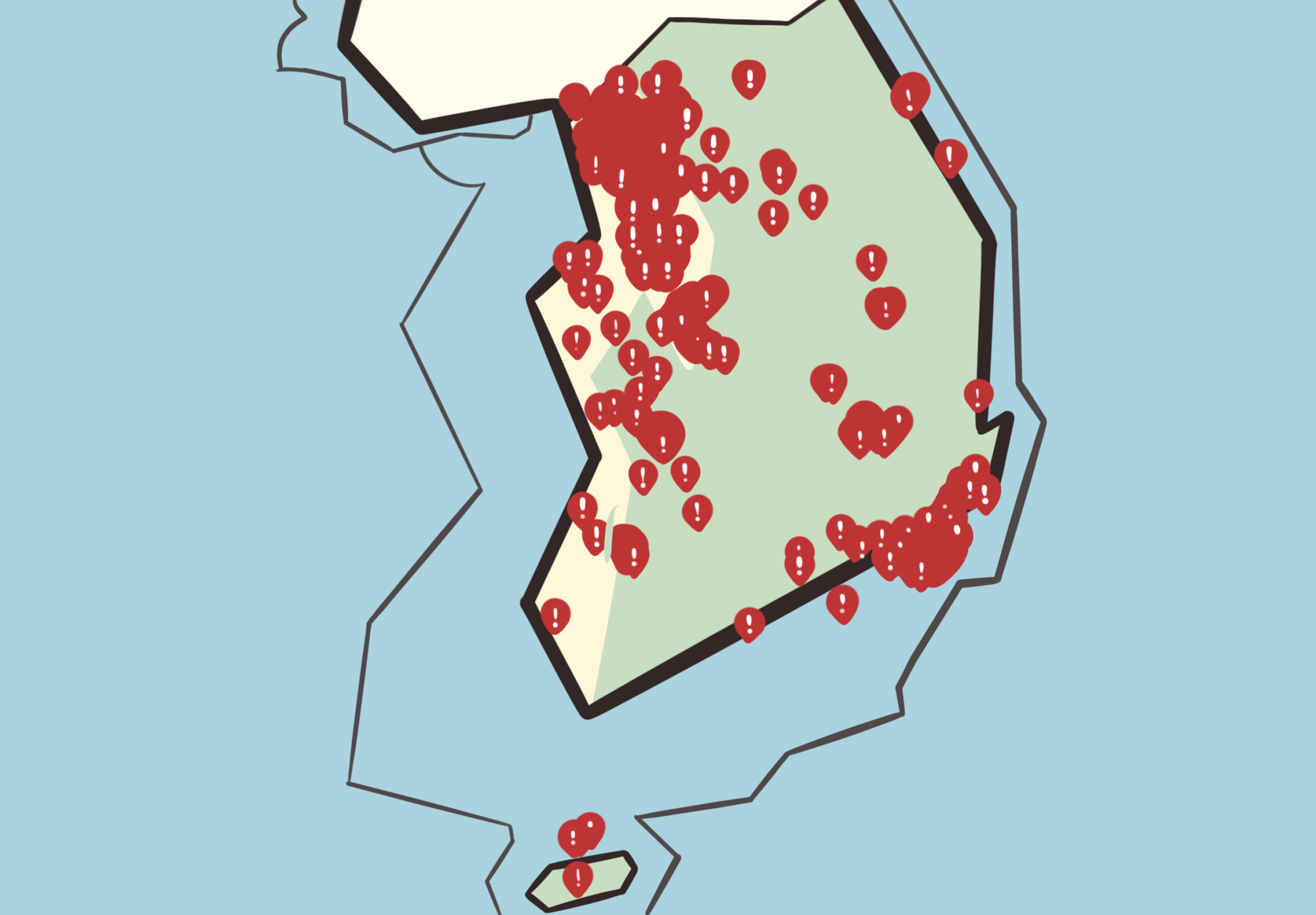

Deepfakes — images and videos that synthesize faces with adult content via artificial intelligence — recently plunged Korea into a national crisis, with over 2000 victims affected by this deceptive technology.

Such illicit videos originally victimized celebrities. Hyunsang Lee from the Big Wave AI Data Analysis Team said, “With the popularity of K-pop culture, young stars and celebrities have been subject to deepfakes. However, with the further proliferation of social media, the target range has expanded to the general public.”

But as more people flock to this technology, these crimes have begun to creep into the lives of unprotected adolescents. As of Aug. 26, deepfake crimes have affected over 200 schools nationwide. Criminals typically capture photos from social media accounts and overlay them onto mature content. They then publicly distribute the content on platforms such as Telegram, an open-source messenger infamous as a haven for crime.

Although the public education system and the international school sphere in Korea share few commonalities, deepfake crimes broke through this demographic as well. At an international school in Korea, a student’s face was plastered onto adult material by one of their peers and shared with their friends.

The widespread nature of these crimes leaves many young women in fear. “I kept reloading my account to see if I was on the list because I noticed the middle school I attended was included on the list … I was afraid of being involved in that situation, I was afraid of being a victim of the crime,” sophomore Lucy Kim said. “The thought of my face displayed in deep-faked videos and seen by multiple people was terrifying.”

Isabel Bae in seventh grade said, “It’s really easy to create deepfake content. I would be really scared. I was scared. After hearing about the incident, I sure did make my account private and took down a lot of my posts.”

Contrary to the perception that only young women face these injustices, men also fall victim to this crime on platforms such as Telegram and Line. “I registered as a Litecoin investor on a KakaoTalk open chatting room, and I was invited to a Line chatroom,” ‘J’* said. “I became suspicious because Line has a reputation for being on the dark web, and it also asked me to put in my name and phone number. I should have stopped there.”

He said, “After I put in my information, they pulled me into a video call. I hung up after four to five seconds, but the criminal captured my face from those four to five seconds and put it on explicit videos and threatened to send it to all of my friends and family. They said they would delete the video if I sent them 1,000,000 won.”

‘J’* described his experience: “I was scared because I kept thinking, ‘What if it was sent to someone else? What if someone sees me on Telegram? It was almost impossible for me to think rationally for at least a couple of days.”

Platforms on the dark web provide a secure environment for perpetrators to distribute and share illicit content under the mask of anonymity. “Such crimes occur in the virtual world where transactions between criminal entities are private,” Lee said. “This makes it extremely difficult to monitor and prevent … As the quality of deepfake videos improves — which it will — detection becomes increasingly difficult.”

This brings many victims to the edge of despair. “I ruminated a lot on how to solve this problem. I had a long conversation with my parents, and I even reached out to the Digital Sex Crime Victim Support Center. However, they told me that they couldn’t do anything to stop the video from spreading unless the police find the criminal,” ‘J’* said. Fortunately, ‘J’ did not send the sum over to the criminal.

Cultural factors amplify the burden the victims face as well. Confucianism’s hold on Korea shushes the discussion of “scandalous” topics such as sexual assault even amongst family members. Consequently, they feel as if they are the ones to blame and hesitate to reach out, over 80% of cases go unreported.

‘J’* reached out to his parents, but Kim said, “Although I’m close with my family, I would be reluctant to tell my parents … I’m not sure why. Perhaps I was worried about being misjudged and feeling ashamed.”

The taboo around such topics causes superficial, outdated sex education and silences calls for precautionary measures. “I wasn’t told anything about it at school,” Bae said. “But I do think that it should be more talked about because most students are active on social media [and] not a lot of teachers know about it.”

Kim hopes to see daily advisory sessions that address such crises and protect students. “I believe [advisory periods] need to focus on subjects and events closely related to what’s happening in the real world. I don’t really get why this crime hasn’t been officially mentioned.”

Although international schools are more in the loop with the American system and use Common Sense Media, a cookie-cutter Social-Emotional Learning and Digital Citizenship program, they must not throw a blind shoulder to local issues.

Schools must actively fight against the cultural taboo and educate students about these crimes to foster a supportive environment where victims can reach out for help. Daegu and Ulsan, among many other cities, have implemented “Emergency Education on Preventing Deepfake Crimes,” where they teach students precautionary measures and actively strive to eradicate sexual crimes in schools.

However, such education programs also fail to adequately protect victims. “The school taught us that criminals can breach your data from various social networking platforms,” ‘J’* said. “But the programs focused more on the idea that anyone who exploits deepfake for sex crimes would face legal consequences because the perpetrators are often classmates of the victims.”

Politicians began legislative efforts to protect victims. Per the Government Protocols against Deepfake Sexual Crimes in September 2024, the Korean government made watching deepfake pornography illegal to prevent the spread. Despite these efforts, public policy has a long way to go, and targets still suffer. The National Assembly and women’s rights organizations criticized the police’s lack of action in the National Assembly’s Audit of State Affairs.

In the absence of political solutions, stakeholders must take measures to protect themselves and others. “Solutions that can be implemented now are limited, but they still exist. Recognition and filtering systems that detect artificially made content, automatic watermarks or differentiation codes that are detected to be made from deepfakes, and the fortified protection of users are some measures that can be taken,” Lee said. Users can also restrict viewers on social media accounts, regularly monitor impersonations, or implement digital watermarks.

Nonetheless, students must come to terms with the fact that they too can fall prey to this crime. ‘J’* said, “I think a lot of kids don’t think that they could be the victims of deepfake crimes. I was lucky enough to handle this appropriately, but everyone should be aware that they too can be the victims and they should take measures to protect themselves.”

This story was originally published on Jets Flyover on October 7, 2024.