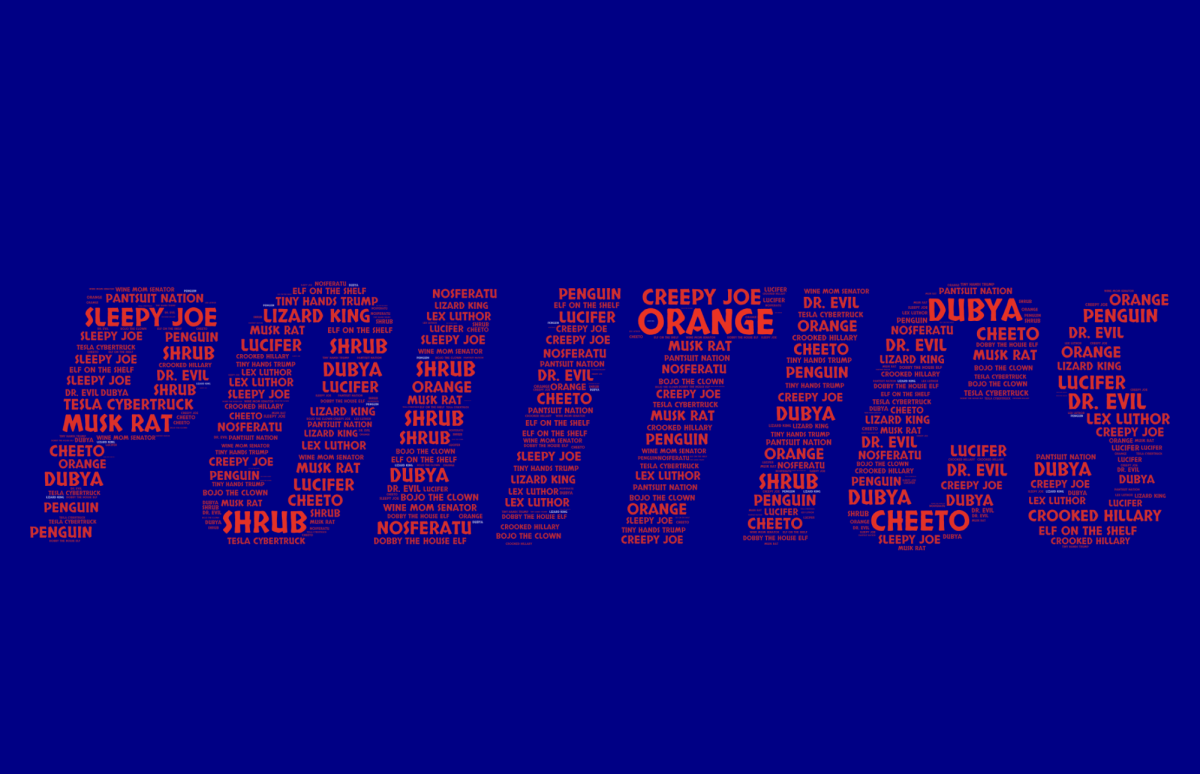

As the creator of the cover story on this issue, I am once again collecting data on an election. I sent out surveys online and made them anonymous with a “comment” section for people to type out their thoughts. An interesting observation is this: many comments, written by supporters of both candidates, employ similar language. To paraphrase, 90% of the comments are either “if she wins, our country is doomed” or “we all know his victory in this election is the death of our democracy.

More interestingly, many students state they are “not too political”. Thus, these two languages combined create an almost contradictory phenomenon: “I’m not too political, but one side is absolutely good, the other side is devil in person.”

These comments are not only present in my Google Form. I believe it’s prevalent on Instagram comment sections, X posts and even in our conversation, especially among Gen Z adolescents. This pinpoints two problematic social norms worth discussing: the avoidance of public political discussion and the heated rhetoric in political discussion today.

Doug Valentine, assistant teaching professor of sociology at University of Missouri, Columbia, explained that social norm falls on a spectrum, one side is pragmatic to the society, the other side is harmful and nefarious. The social norm of avoidance of politics utilizes both sides of the scale with potential damaging impact.

“You definitely avoid interpersonal conflict if you stick to “safe” topics of discussion in a mixed group. However, it also means people’s pre-existing views are never being challenged, and there are plenty pre-existing views that deserve challenging,” Valentine wrote in an email interview. “If you cannot talk about politics, when will you or those around you hear perspectives that disrupt their preconceived notions of government, race, gender, social or economic policy, or global issues?”

The fact that our views aren’t being challenged is linked to our political position. If we believe firmly that we are correct and equate the other side to the enemy of the republic, we obviously don’t seek challenges to our position.

But how did we form these obstinate and absolute positions? It very much has to do with the second problem: heated rhetoric. Valentine continued to explain that, candidates often uses heated language in political campaigns, and it’s not a cycle the society can break.

“When the consequences of political campaigns and elections have material importance (gaining or losing rights, the adjudication of law, tax policy, etc),” Valentine wrote. “Using harsh rhetoric to gain an advantage could mean life or death.”

The election cycle rhetoric is then enhanced by the media we consume today. Political correspondent and columnist at St. Louis Post-Dispatch Joe Holleman, who has been working in media for over 42 years, explained the dramatic change of media standard over time with the emergence of social media, which no longer judge a piece of content by evidence and logic.

“A lot of people judge their argument by whether other people like it.” Holleman said. “There is no longer that detailed debate of issues- it’s what can I say in 30 seconds that’s gonna make people remember me.”

Holleman extended his analysis to legacy media as well. Media companies responded public’s love for “hot take” over reasonable arguments by feeding them more arguments viewers liked to hear, and over time, shifting one way or the other on the political spectrum.

“I can think back to the years when there was no Fox News or MSNBC News. There was just the news,” Holleman said. “Now what has happened is that because we’ve realized that people are trapped in little silos, we sometimes feed information to those silos.”

The effect of an individual’s unchallenged political view with extreme rhetoric played out in many ways. Valentine suggested that it is wrong to ban all the heavy rhetoric, however, an overuse of them cause these words and phrases to lose their meaning.

“If historians of the rise of Naziism say ‘that rhetoric sounds exactly like the rhetoric used during Hitler’s rise to power,’ you need to be able to say that,” Valentine wrote. “[But] people can absolutely be far too quick to engage in that rhetoric: if everything is Hitler, then nothing is.”

The other damaging effect is the villainization of others who hold different political views from ourselves. A study conducted by Nathan P. Kalmoe, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Monmouth College, showcased that extreme rhetoric often makes violence against the targeted group seem more legitimate, and thus, increase political violence. On the other hand and more commonly, Holleman explained villainizing groups by their views polarized public discussion and helped people form a firm and extreme political position.

“It’s either ‘I’m for it’ or ‘I’m against it’. And ‘I’m right, and you’re stupid’” Holleman said. “It used to be ‘I’m right, you’re wrong’. Now, it’s even worse than that: I’ve got to make you look like you don’t know anything you’re talking about. That really hurts the discussion.”

In practice, this hyper-bipartisanship harms the public during elections. Ayanna Shivers, who served as the mayor of Mexico, MO from 2019 to 2021, and became the first Black woman to hold the position, noted during the 2018 election Missouri as a whole voted in favor of laws and initiatives that supported higher wages, protecting unions, right for people to congregate and to advocate on the behalf of others, but the voters also elected officials that voted against all these positions.

“A lot of people only vote for a party, and they don’t even think about the issues at hand or what most of these people are talking about,” Shivers said. “They cannot make the decisions in and of themselves.”

A society holding stern political positions and using heated rhetoric, therefore, as I’ve outlined, is not a beneficial one. To reverse the harmful effects of it on society, the first step is to distinguish the over-exaggerating rhetoric. Given the incentives of the media to attract viewership and politics to attract voters, Holleman recognized that the media is always repeating the same, tense script during elections.

“It’s kind of funny,” Holleman said. “It seems like every election, this is the one that democracy hinges on, but then again, I go back and I remember, you know, 40 years ago, that’s what it was like too. This election is the most important election of your entire life.”

After admitting to the media bias, and therefore conceding that our position is not always, absolutely correct, and people with different views are not always, absolutely wrong, we need to be open to challenges. Valentine believed that it’s never good for us to stay silent on political topics – even for the people who are “not political” – since every area of our life is influenced by policies. These conversations don’t have to be hostile.

“We have a tendency to associate folks on ‘the other side’ with the most offensive things that we dislike about the other side,” Valentine wrote. “but we should ask ourselves if we necessarily agree with everything associated with our candidates. The answer is probably not, so how can we give a little grace to others and let them (if they want [to]) explain to us why they feel the way they feel.”

Besides discussion in public, another way to challenge our view is by disrupting the cycle of echo chambers provided to us by the media. Holleman suggested people should be actively seeking out materials that differ from their position and be educated.

“We always tend to believe that people who agree with us are much smarter than people who don’t. Find someone who doesn’t agree with you and see what they have to say, then make your decisions,” Holleman said. “The more you look into real analysis, as opposed to hot takes of situations, I think you have a better idea [of the issue].”

Finally, we need to humble ourselves in our understanding of the political world – we cannot be experts on every issue. Holleman used the analogy that the modern citizens’ understanding is “a mile wide but only an inch deep”. To better the political discourse, he suggested people focus on a few issues and study them in-depth.

“Find the things that you think are crucial to the existence of our republic and read books,” Holleman said. “Don’t have your knowledge just being what you heard on the nightly news or what you read on Twitter.”

As a member of society, it is impossible to completely isolate yourself from politics. We all have political opinions, knowingly or unknowingly. The solution of different views is not to avoid challenges, but to have the humility to recognize our view is imperfect and should be challenged in a good natured way. Shivers’ piece of advice for the younger generation, drawing from her own political experience, is to value the importance of human connection.

“I think to be successful- you have to be able to connect not just with people who think like you, believe like you, but also being able to have conversations, and being able to collaborate,” Shivers said.

This story was originally published on Corral on October 28, 2024.