Editor’s Note: This article was updated on Dec. 3 at 3 p.m. to correct a source’s last name from Richard Soriano to Richard Soriano Jaladoni.

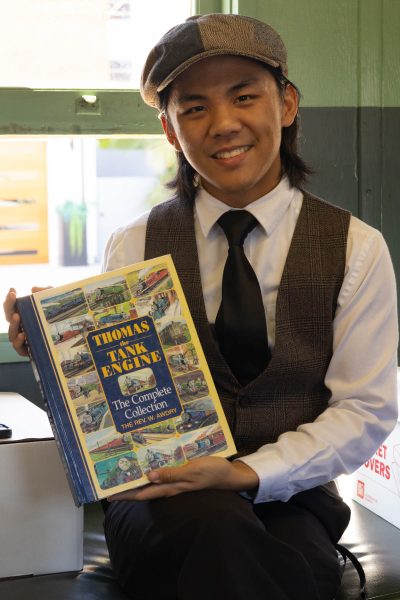

The first thing you notice about Richard Soriano Jaladoni is his hat.

He’s always wearing this murky green newsboy cap. Old-timey, but not old – no signs of dust or wear and tear.

One might imagine he dusts that cap every night along with a pristine collection of newly restored British model trains. A black and white scene straight out of a vintage cartoon from the ‘20s.

Jaladoni has this way of speaking. It’s smooth and intentional, especially when he’s talking about trains. It’s quite the hobby for an 18-year-old engineering major at El Camino College, but Jaladoni’s been charmed by the idea of trains ever since he was young.

For the past year and a half, Jaladoni has been a key member of the Lomita Railroad Museum, which is dedicated to educating the public on both the history and future of railroading. He and four other staff members, all under the age of 27, work as tour guides, groundskeepers and historians.

“We’re definitely not here for the money,” Alex Barnett, the museum’s 21-year-old manager said with a laugh.

Instead, their team is focused on uplifting the spirit of the museum. Each team member brings their passions to the workplace, cultivating a rich atmosphere.

It’s a place full of combined knowledge and skill sets. One person is a talented artist, another is a charismatic networker. They learn from each other and grow together as the museum grows with them.

They teach and encourage each other and anyone else sharing their passion for trains. Jaladoni has not been a stranger to the judgment others push onto him because of his interests, so he wants to make the museum a place where like-minded individuals feel safe enough to express themselves.

Here, people can feel pride toward their love for trains.

Jaladoni’s interests began like many others. He was 2 years old when he was introduced to trains. His mother often played train documentary DVDs, including “Thomas the Tank Engine.”

It’s a common entry into the hobby for children nowadays, but it was different for children back then.

Bruce Openshaw is a 75-year-old employee at The Original Whistle Shop, a model train store in Pasadena. He’s seen a range of ages come in and out of the store during the eight months of his employment, from young children below the age of 10 to elders in their 90s.

Openshaw was introduced to trains when he was a young boy. He and his father would often work on model train projects together, picking through pieces of a Lionel train set and watching it circle the track. It was his generation’s gateway to trains, a secret language he spoke with his father.

The age range of individuals interested in trains is diverse, according to Openshaw. Many children get involved in the hobby through a spark of fascination, and their parents help by funding it.

“I’ve noticed one thing, the small children, they come in and we’ve got the Thomas [the Tank Engine] stuff here,” Openshaw said. “They come in to play. A lot of them, they’re very young, and they don’t realize what a train is but they love that!”

With the influence from both the children’s show and the original copies of “Thomas the Tank Engine” books from the ‘40s and ‘50s, Jaladoni’s interest piqued into a fascination for British trains.

His fascination, however, set swift concerns for his parents. Their idea of trains was attached to a children’s show rather than a stable future.

To his mother, a geriatric nurse, and his stepfather, an aerospace engineer, there was no money to be made in railroading. There was no future in a childhood dream.

Jaladoni had developed an opposite lens on life. His idea was that a good life comes from experiencing the things you love. To follow someone else’s standard would be a boring life to live.

“I’ve always believed that when you do what you love, and you can do it well, then the money comes naturally,” he said.

Understanding of Jaladoni’s interest wasn’t only scarce in his household, but also in school. When he was attending South High School in Torrance, he became all too familiar with the “Train Guy” comments his peers threw at him.

Something that, for so long, brought him a sense of wonder had become like a red stamp across his forehead branding him as different from everyone else. It was the pandemic and its quarantine that brought him closer to comfort, not only toward others with similar interests but also closer to himself and his hobby.

On Instagram, Jaladoni searched for a niche within a niche. Train hobbyists may be hard to come by on a day-to-day basis, but British train hobbyists were nearly impossible to find in America.

When Jaladoni was 14, he connected on the platform with then 15-year-old Adam Maunser, a boy from England. Maunser introduced Jaladoni to other boys interested in British trains. For the first time, Jaladoni was exposed to others just as passionate about trains as he was.

Freedom was a breath of fresh air with his group. There were no consequences for being unapologetically themselves.

The language of trains was buzzing vibrantly, solidifying their connection.

“Through that, we were able to connect in a way that not many people get to,” Jaladoni said.

Despite his parents’ concerns, Jaladoni grew into an individual of intellect, curiosity and eagerness. Railroads had captured his bright eyes from a young age, so engineering seemed like the perfect major. It gave him a good foundation and background in the mechanics of railroading, but also something he could lean on for a more stable career.

While he was busy collecting model trains and learning more about railroading every day, he was also setting up for his future.

Jaladoni’s determination was clear: this hobby was not going away. This underlying empowerment simmered within him, emitting an energy that everyone around him could feel.

His parents felt it. Seeing their child step into his prime was an eye-opener, and they continued to evolve into a strong support system. In 2023, they decided to fund Jaladoni’s trip to England, where he would finally be able to meet with his gang of spiffy train heads.

“They [parents] don’t see the fruits of your own labors until you really start expressing how much you love it and how beneficial it really is,” Jaladoni said.

He stayed up for 24 hours to prepare for his trip. The plan? Stay up all day, sleep through the entire flight and wake up in a new world – England.

“I woke up when we were landing in Heathrow Airport for the first time,” Jaladoni said. “I look down and I see this big cathedral-looking building and I was like, ‘Oh, I’m in England now!’”

Walking up to Maunser and his father after going through customs, Jaladoni immediately noticed the height. He was about 4 inches taller than Jaladoni.

He was blond, well put-together and, like Jaladoni, well-spoken.

Maunser and his father welcomed Jaladoni with open arms, and the boys hit it off right away. It was as if the years they’d known each other were their entire lives.

The railways in England were a far reach from the photos he was so used to seeing through pictures. In person, he was set on the desire to move to England where he would one day become a train engineer.

The move, of course, would have to wait, but the excitement took hold of him throughout the trip. He’d imagine himself getting his hands dirty, a brain full of history, a body running through an English museum like a steam engine.

It was his group of online friends that helped set a tone of acceptance for him. With them, he was able to explore and honor his interests without shame.

The Lomita Railroad Museum was another catalyst propelling Jaladoni’s dreams into reality.

The Lomita Railroad Museum sits nestled within a residential community, hidden from the rest of the city. It’s a quaint structure. The building itself is shamrock green while the arches curve around the windows and the pillars. The roof is a pale yellow.

Beside the building, “she” sits. A shiny black, full-size steam locomotive steals the show.

After the museum’s founder, Irene Lewis, died, she left behind a large sum of money to keep the museum running. Currently, it is funded through the city of Lomita, the museum’s gift shop sales and rental facilities.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum took a big hit. It was closed for two years and many of the staff and volunteers left. Coupled with the lack of interest from the public, the museum was left with a little less life than it first began with.

It was up to the museum’s current team, this new generation of train lovers, to bring it all back.

It wasn’t just the undeniable passion, but the action. Together, they planned a plethora of events, most notably, their annual Night at the Railroad Museum summer event.

A Night at the Railroad Museum was created as a “live history” event, where attendees dress in attire from the 1850s-1950s. There’s a live band playing jazz, people dancing around the courtyard, a vintage car show and even a historical reenactment group.

“We did have a generational loss there [because of COVID]. We really, I believe, brought some of the soul back to the museum after that,” Barnett said.

Walking into the museum is like being transported into a vintage rail station waiting room.

Lanterns and marker lights hang from the wood ceiling. Framed photos and traffic signs line the walls. Glass case boxes display artifacts, freshly restored by staff.

On a sunny Friday afternoon with the first autumn breeze sweeping through the leaves, Barnett sat at a folding table pushed against the wall next to the window in the museum’s small office. Min Tsolomon, another staff member, sat at one of the desktops, mumbling about research.

Tsolomon had purple-streaked hair, round glasses, and wore vintage attire – an Edwardian navy blue skirt, a white blouse with a ruffled collar and black ankle boots.

Lola wasn’t too far away, all warm and snug in a high chair in the corner of the room. She’s a grey tabby cat who often spends her time in the museum.

Jaladoni was sifting through a box of artifacts, hands moving back and forth between the box and the desktop where he was editing his plaque design. Each time, he’d speak about these inanimate objects as if they were living, breathing beings.

“Context clues… where are you from?” he said, holding up a rectangular slip of paper. His eyes scanned the surface as he hummed an old-timey tune to himself.

“New Jersey…1944, so… intuition says that’s too late.”

He was in his element, all parts of his mind whirring like the mechanical workings of an engine. He was soaring through a box full of history, hands made to take care of the past. A heart that pumped for the hobby — his hobby.

Despite judgment from family and peers, he has worked his way into this environment led by passion and resolve. Moving on from past insecurities, Jaladoni has looked outside of himself to build community, and now he’s able to fully dive into what he loves.

“You can empower yourself to find your own people and embrace what you love,” Jaladoni said.

This story was originally published on El Camino College Union on November 29, 2024.

![Within the U.S., the busiest shopping period of the year is Cyber Week, the time from Thanksgiving through Black Friday and Cyber Monday. This year, shoppers spent 3.3 billion on Cyber Monday, which is a 7.3% year-over-year increase from 2023. “When I was younger, I would always be out with my mom getting Christmas gifts or just shopping in general. Now, as she has gotten older, I've noticed [that almost] every day, I'll open the front door and there's three packages that my mom has ordered. Part of that is she just doesn't always have the time to go to a store for 30 minutes to an hour, but the other part is when she gets bored, she has easy access to [shopping],” junior Grace Garetson said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/DSC_0249.JPG-1200x801.jpg)

![French teacher Marieme Toure serves a plate of the Senegalese food she prepared for her AP French Language and Culture class, to senior Faiza Syed. “I never had Senegalese food before,” Syed said. “I thought it was so cool that she was able to bring a part of her culture [and] background to us.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IMG_0798-1200x906.jpeg)

![NEW CHALLENGE, NEW TEAM MEMBERS: Every season, VEX creates a new game that robotics team members are faced with and have to build a robot to compete in. This year’s game forces students to create a robot that is able to stack rings onto mobile goals in order to score points. The change in games each season is something that robotics teacher Audrea Moyers appreciates.

“One of the things that I like about VEX is that they have a new problem to solve every year,” she said. ¨Even though the equipment’s the same, they have to analyze the game, and they have to come up with solutions that are unique that year. They are using their knowledge from prior years, but they have to kind of redesign a problem.”

As returning teams were faced a new game, some new teams and members had to adapt to a uncommon playing field and game.

“Three of our four teams were competing for the first time this year, and they had very different experiences match to match, so I think they learned a lot,¨ she said. ¨It’s hard just watching a video online to know how it’s actually going to be in person, so they all learned a lot about what gameplay is like, how to work with an alliance partner [and] how to adapt during the day to changes.”](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_9283-1-1200x800.jpg)