“Putting someone in prison may be the right thing to do, but leaving someone in prison without an opportunity to grow and change is something that doesn’t work for anyone, doesn’t work for us as a society at all. It’s just a waste of human life and tax dollars. It’s criminal in itself to do that,” said Cheryl Hajjar, the visual arts chair. She works with an organization, Rehabilitation Through the Arts, dedicated to helping incarcerated individuals grow and change by creating art.

Incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people who worked through RTA recently showcased their art in the ‘Windows and Doors” exhibition organized by Hajjar at the Riverfront Library Gallery at Yonkers Library. The exhibit will be open to the public until Jan. 3.

RTA’s program works in ten maximum and medium security prisons in New York and in one facility in California. The program leads workshops in theater, dance, music and creative writing.

Hajjar was first introduced to RTA in 2007 when a friend invited her to see a play inside the Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York. Although she had visited Sing Sing before when her brother was incarcerated there, she said she was moved by the different and unique experience, and shortly after she worked with the organization to create visual arts classes that mimicked a college arts program.

When she began teaching the classes, Hajjar said most men in the prison did not have many positive educational experiences or much exposure to art, so she would bring news from the outside art world and photographs of art exhibits she visited to Sing Sing. Each man had different previous experiences with art. She said, “Even though the group of men that came to the art class on Tuesdays came with a wide variety of skill sets, there was also this developmental piece that had to do with very limited exposure to engaging with art in general, or engaging with creativity; it wasn’t something that was nurtured or fostered in their early life.”

Hajjar explained her motivation to teach art classes at Sing Sing was the same reason she chose to be an art teacher: to help people discover that art is available to everyone. “[Art is] just something you can do that can help you kind of navigate your lived experience, your identity.”

One former member of RTA, Gary Butler, said that when he was first incarcerated he had trouble taking orders but was enrolled in certain programs such as assisting cooks in the mess hall. When he refused to follow directions he would get “keep-locked,” in which he was locked in his cell for 15 to 20 days. He said after the kitchen program he was placed into another program he could not cooperate with, and then received art class by the facility’s administrators as a punishment.

After transferring to Sing Sing prison, he joined the waiting list for the RTA program and eventually became involved. He said “I think [RTA] gives incarcerated individuals a place to go where they can be themselves. You know, you’re not going to see guys [dancing] in the cell block. You got to have on your hardest face.”

Hector “Bori” Rodriguez, another former member of RTA, said art helps incarcerated individuals learn the emotional intelligence necessary for developing accountability. He said RTA allowed him to tap into his emotions and understand what led him to commit the crime and to tap into his emotional intelligence.

Eventually, the thoughtful and personal artwork made by RTA members could be shown to the public. However, the number of people who could see the art exhibited was limited because they had to be invited in by RTA and have a background check completed by the Department of Corrections. The approved guests would come to see the exhibit and then the play.

Hajjar said that at the exhibits inside the prisons, the public could interact with the artists. “It was exactly like if you go to an art opening in a gallery or in a museum and the artist is present, and the public could really talk with [the artists] about the work they’re doing, and the meaning it had,” she said. She continued, “The more opportunities that came up like that, where it wasn’t just me and this group of guys sitting in a room on a Tuesday night making art, but also having their voices, their visual voices, heard by outside people, was very exciting.”

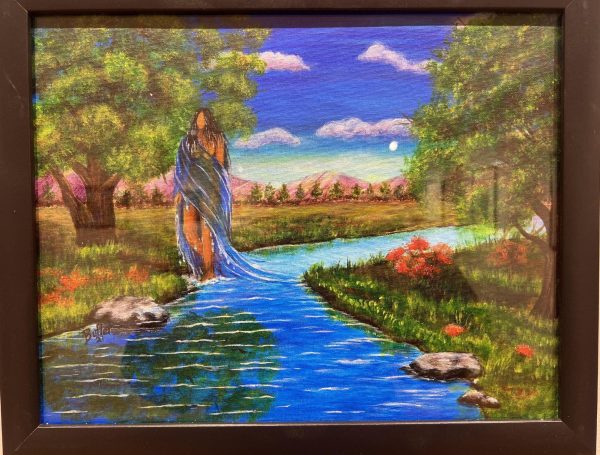

Butler said he most enjoyed painting wildlife, animals and landscapes while incarcerated because the wide space of nature contrasted with the limited space he was given in prison. In one piece of artwork, he painted a landscape and a glowing river with a woman walking next to the river bank with water wrapped around her like a shawl. He said, “I was expressing that water is life, and women are the water of the Earth, because there’s no life without women.”

(Elaina Barreto)

Rodriguez said he includes many images of Shakespeare theater masks to demonstrate the many “masks” individuals have to wear and adapt in prison in order to survive.

Hajjar said other opportunities to exhibit the artwork of the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals have come up throughout the years: around 2010 an opportunity came up at the Ossining Art Society to exhibit art to an even broader audience, and later the Austin Library Gallery offered a space to exhibit work as well, where shesaid around 30 artists from different facilities participated in the exhibit.

According to RTA, out of the 1.8 million incarcerated people in the United States, 95% are going to be released. Within three years, however, 60% of the formerly incarcerated return to prison. The recidivism rate, or the number of convicted criminals that commit another crime after being released, reduces drastically with members of RTA: less than three percent of RTA members return to prison. A reduced recidivism rate saves taxpayers millions of dollars, as the U.S. spends more than 80 billion dollars on incarceration.

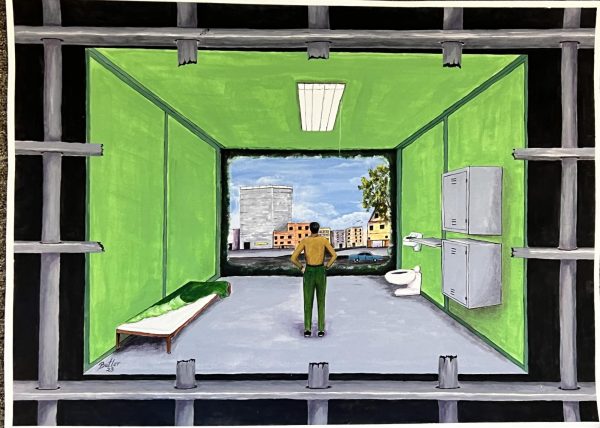

Many artworks at the exhibit feature prison scenes. In one of Butler’s paintings, he said he tried to depict change through an image of a man in a cell. He said, “I was trying to express that people have made mistakes that they intend to come back from. The man is standing in what’s supposed to be a cell, and he’s imagining a [city] scene on the back wall, so he’s looking into his past. He’s standing in his present, which is the cell, and then behind him, I have bars painted that are broken, and the suggestion is that his future is behind him. The broken bars mean that he’ll never come back.”

(Cheryl Hajjar)

Hajjar said she believes education can help many incarcerated individuals. Rodriguez attended Bard College through the Bard Prison Initiative Program. According to Bard Prison Initiative, the program gives incarcerated individuals an opportunity to “enroll in Bard College courses, earn Bard College credits, and graduate with Bard College degrees.”

Rodriguez said he learned a lot about feminism through his education at Bard College, which inspired aspects of his artwork. In his art piece Fruto de mi Borinken, he said he painted a woman’s body rising out of a tropical plant to represent a woman’s figure as powerful and to show people that women are “as strong as an oak tree, but as fragile as a flower.”

Hajjar has heard of the Bard Prison Initiative and other programs that work to provide education for incarcerated individuals. She said “I have a great deal of respect for programs like the Bard Prison Initiative and the facilities that collaborate with Bard. I really do believe that education is a way out. And by out, I mean everything from out of your own heads, psychologically, and all of the burdens you carry as an incarcerated person or as a non-incarcerated person. And I think that the justice system is beginning to clearly see that; they’re beginning to see that prisons should not be a punishment. There is no way that corrections or even the police can continue to lock people up for crimes without rehabilitation.”

While education is important for individuals seeking jobs after being released, it can also help them adjust to life after releasement. Hajjar said, “When you’re incarcerated, so much is done for you. Other people are deciding what you’re having for your meals, what you’re wearing, how your time is structured, and then all of a sudden, when you’re released, how [do you] know how to create a life and structure [your] time, money, and socialize?”

Butler left prison in 2023 and now works at American Concrete Institute (ACI) as a grade one inspector. In the future, he said he hopes to get more certifications to advance in the field.

As Rodriguez said on his website Bori Creates, after being released in 2023 he was accepted into the Yale Prison Education Initiative College-to-Career Fellowship. Even though the art created by RTA members is not for sale, Rodriguez does have an online store that sells clothes, phone cases and other items decorated with his artwork. He said he plans to “enhance my artistic skills and knowledge of mass incarceration and advocate for higher education and art programs in prison.”

With many incarcerated individuals leaving RTA with the skills needed to reenter the workforce and society, Hajjar said, “I’d like for people to know that we don’t need to stand in judgment in our society the way we do and that everyone deserves another chance.”

This story was originally published on Tower on December 23, 2024.