It’s pasta day, and by 9:30 a.m., the smell of meatballs and tomato sauce fills the air as sounds from large pots and pans ring the room. The lunch bell will ring in a few hours, and hundreds of hungry students will stampede through the halls, searching for fuel to power through the end of the school day.

However, if these students were to think of lunch, they would likely think of the food itself, while the people and work that goes into making the lunch are often forgotten.

Food services lead Gail Horn has worked at Carlmont High School for 10 years and discovered a similar routine yearly. It all begins when Horn arrives at the cafeteria at 6:30 a.m. and immediately gets to work.

“We must figure out how many meals we will sell if each item arrives. We have to take the temperatures of the water, the hot water for washing the dishes, the refrigerator and freezers,” Horn said.

But before the workers can begin cooking, the produce must reach the hands of the cafeteria workers.

“We have a vendor for milk, and he comes every Friday. We also have a central kitchen that gets their stuff from Gold Star and Cisco, and they bring it to us when we need it,” Horn said. “Say barbeque chicken. On Wednesday, they sent me the chicken, the corn muffins, and the corn on the cob.”

The rest of the staff arrives between 7:30 and 9:00 a.m. During this time, the cafeteria team must also serve prepackaged breakfast.

Following the breakfast service, the team must prepare the ingredients for the day and turn on the ovens and stoves.

In addition to that, another critical part of the school’s lunch lies in the hands of food services worker two, Dolores Reyes.

“I start counting the fruit from the day before and washing the fruit that we have today,” Reyes said. “Sometimes we have to do around 600 pieces of fruit, so we have to ensure they’re nice and clean.”

Afterward, Reyes heads back to meet with the rest of the team and help with the food prep. Workers put trays of meatballs in the oven while some pour pasta into large pots to get boiled.

After cooking, the meatballs are placed on large trays and put on a rack to cool, and the workers must take the temperature of the food, which is essential in ensuring it is safe for student consumption. The food must reach a temperature of at least 165 degrees Fahrenheit and is suitable for 4 hours before being discarded.

Employees must follow other safety guidelines during food preparation, such as wearing gloves and attending the appropriate training.

“You need to get a Serve Safe Certificate and the training to handle food and sanitation,” Horn said.

After the food is cleared to be safe to be eaten, the staff use two large preparation tables to package the meals.

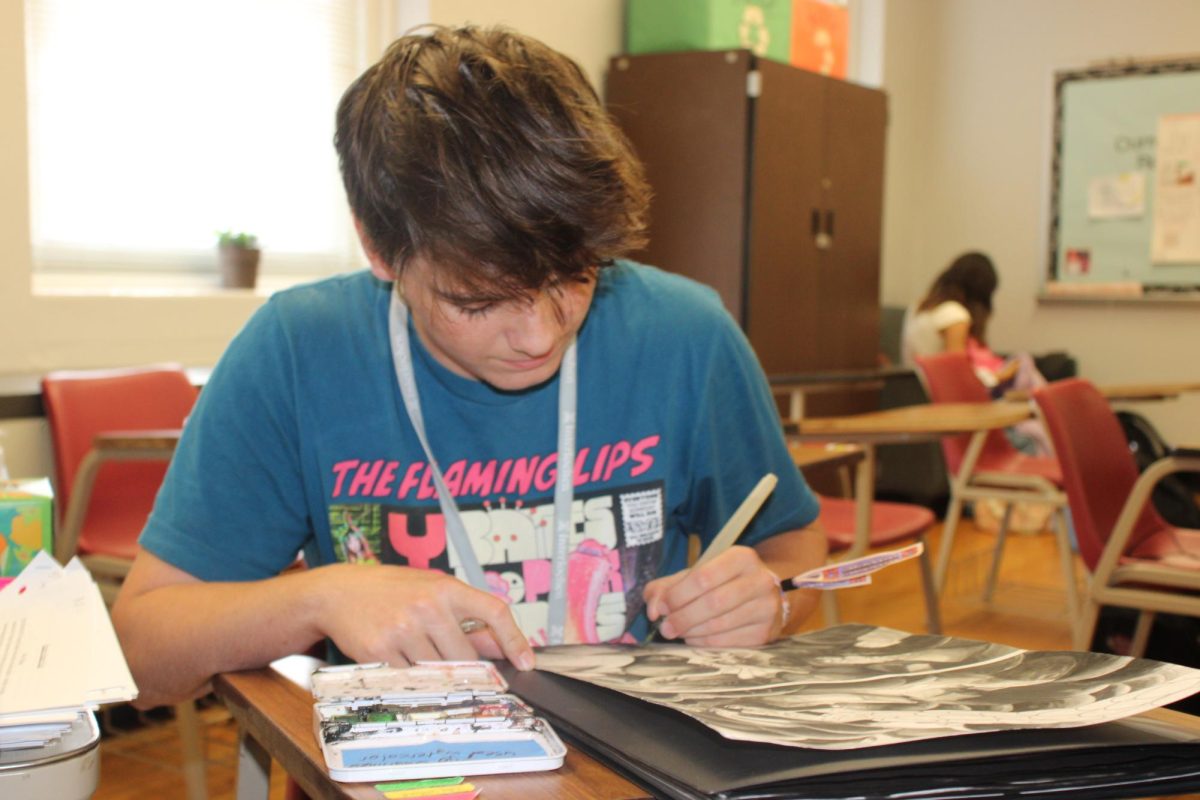

(Jalen Wong)

Paper trays are laid across the preparation tables as workers scoop spoonfuls of pasta and peas into each container, ensuring enough food for the students. Workers take the prepped trays to be sealed by plastic by a machine.

During this time, a worker is in the back washing the used cooking trays, pots, and pans.

The work is not easy, and workers often spend hours making out the number of meals they need.

“We start prepping at 8, and then we have to wait for it to cook. You don’t get done until 11,” Horn said.

The meals are then placed in large warmers and others in sizeable insulated food bags that must remain over 140 degrees Fahrenheit to be safe for consumption. The food is then placed on a cart and sent off to another lunch kiosk on the campus.

Lastly, the food is distributed to hundreds of hungry students. Most importantly, the meals are free of charge due to several acts passed by the federal government and the State of California.

History & funding

Affordable or free school lunches date back to the 1940s when President Harry Truman established the National School Lunch Act in 1946, leading to the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) creation. The NSLP program, subsidized by the federal government, provides lunch to students in schools nationwide at lower and sometimes free prices.

According to a report published by the United States Department of Agriculture Food (USDA) and Nutrition Service, 28.6 million students received lunches from the NSLP, and a total of 4.66 billion meals were served throughout the U.S.

Beyond the Universal Meal Program, the school district also receives assistance from the USDA.

“Currently, meals are subsidized by the USDA based on the total number of lunches from the previous year,” said Sandra Jonaidi, the director of food services at the Sequoia Union High School District. “This money is called our commodity dollars; in February each year, we select the products from that money that we wish to buy from the USDA and what we want to send to processors to be further processed into end products.”

Jonaidi oversees food and catering services at schools in the district, such as Carlmont. Managing inventory and food, funded as mentioned above, is integral to the job.

“Inventory is managed by placing orders when the menu item is scheduled. Therefore, we carry a minimum extra inventory. However, it is always a balancing act between supply fulfillment and actual orders. Most of the time, our suppliers have everything, but if not, we either adjust the menu production numbers or change the menu item if needed,” Jonaidi said. “Budget-wise, we always try to manage our money. However, we regularly run in the red. In this case, the district will cover the loss/shortfall.”

Schools and the government have also stressed the goal of purchasing better and healthier ingredients for school lunches. Under the Obama administration and the Hunger-free Kids Act, grain products in school meals had to be made up of at least 50% whole grains while reducing fat and sodium.

These programs rely on cafeteria workers’ work; with them, they are as successful as they are today. They also show the importance of cafeteria workers when providing nutritious food to students across the U.S. However, with this need comes many obstacles.

Challenges

Carlmont has north of 2,000 students; over time, the administration has noticed a sharp uptick in students receiving lunch daily.

“Since COVID, our numbers have gone from 300 lunches to 1000 lunches a day,” said Carlmont’s Administrative Vice Principal, Gregg Patner. “That is significant considering the food must be cooked, prepped, and packaged.”

This uptick in meals emphasizes the cafeteria team’s large workload, yet most work still goes unnoticed.

(Jalen Wong)

In 2010, the median school cafeteria worker worked 25 hours a week for 40 weeks. Since then, this number has increased at Carlmont. According to Horn, three and three-quarter-hour employees who focus on setting up serving stations, washing dishes, cleaning, and serving food, among other various duties, work 16 hours a week.

On the other hand, a seven-hour employee, like Horn, works up to 35 hours a week. The seven-hour employee completes the same tasks but must handle staffing, ordering food and paper products, and paperwork/computer work.

Currently, the cafeteria only has six employees, which is very little for feeding such a large school. Thus, besides the regular cafeteria staff, the cafeteria also relies on student-workers who help at the registers and directly hand students the food. But that itself has posed another problem.

“I am going to lose four student workers after this year,” Horn said. “That will be a challenge because if I don’t have student workers, it won’t work. We only have so much staff and so many registers.”

The staff has also noticed an increase in the number of students who receive lunch. This has led to lines becoming congested and more pushing and shoving. In response, the administration has developed measures to combat this.

“I supervise the lunch lines to ensure there is no cutting and that people behave in line,” Patner said. “We, as an administrative team, decided to use barriers, which have been much more successful in managing the lines. We have also made the line narrower and single-file in certain sections.”

The main cafeteria has four walk-up kiosks and an express line where students can grab a meal in a buffet-style format designed to reduce the wait. There is also another lunch kiosk near the gym to alleviate the demand the main cafeteria receives.

Still, the lunch workers do their best to ensure that they provide students with healthy food while serving a crucial role at the school.

Impact

The cafeteria workers are the unsung heroes at many schools across the nation. They ensure students receive food to help them last through the final classes of their day. For Reyes, the impact she creates also resonates with her deeply.

“The kids need to be fed and have nutritious food. If not, they’re not going to study well. I have a 16-year-old daughter, and I was worried about whether she ate or took food to school,” Reyes said.

The cafeteria staff constantly monitors the students during lunch to ensure that the students retain a healthy diet.

“We have to serve vegetables to make a whole meal. It’s also why we encourage the kids to take the burger and a veggie or fruit, too,” Reyes said.

Despite the large workload, the staff can find constant motivation, which helps encourage them to do more for the students.

“It is nice when you see the kids come and get their food, and you know that they’re going to have a hot lunch and continue their studies,” Reyes said.

Many students, like sophomore Luke Sgro, receive lunch daily and are familiar with the menu options. They have seen many changes in the good direction for the cafeteria but also see room for minor improvements.

“I think that the school lunch options have been on an incline this year and appear more pleasable to me,” Sgro said. “I think days should consistently have at least one of the more favorable lunch options so that there aren’t days where people choose not to eat due to the less appealing options.”

In addition, Jonaidi has many hopes for the lunch service and how the school district gets its food.

“As a densely populated suburban area, it is difficult to find space to grow food. However, I believe that it is possible and am looking down the road at the district to find space so that we can grow our own lettuce and herbs year-round using fork (hydroponic) and container farms,” Jonaidi said.

Overall, the entire lunch service at Carlmont has positively impacted students and people. Despite the many moving parts, they all come together to form a successful system to fuel students and set them up for success.

“We issue 1,000 lunches in under 20 minutes to hungry kids,” Partner said. “It’s a minor miracle.”

This story was originally published on Scot Scoop News on January 23, 2025.

![Senior Dhiya Prasanna examines a bottle of Tylenol. Prasanna has observed data in science labs and in real life. “[I] advise the public not to just look or search for information that supports your argument, but search for information that doesn't support it,” Prasanna said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0073-2-1200x800.jpg)