Editor’s note: This article contains graphic details of a violent crime that some readers may find disturbing. As the case remains under investigation, new developments may arise. Reader discretion is advised.

Every McKinley High School student walks through the halls of the W Building as part of their daily routine, often unaware that nearly 50 years ago, those same halls became the site of one of Hawaii’s most infamous unsolved murders.

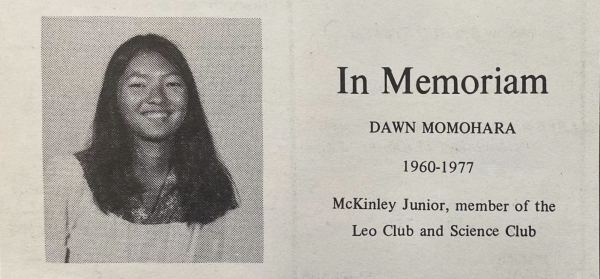

For decades, the question remained unanswered: Who murdered Dawn Momohara? Now, with recent advancements in DNA technology, the Honolulu Police Department has identified a suspect—Gideon Belamidi Castro, a 1976 graduate of the school.

“In the weeks leading up to the arrest, our investigators worked with the Honolulu Police Department’s Scientific Investigation Section DNA Lab and the Honolulu Prosecutor’s Office to establish probable cause for the arrest,” Lt. Deena Theommes of the HPD Homicide Detail said at a press conference in late January.

A Friend to Remember

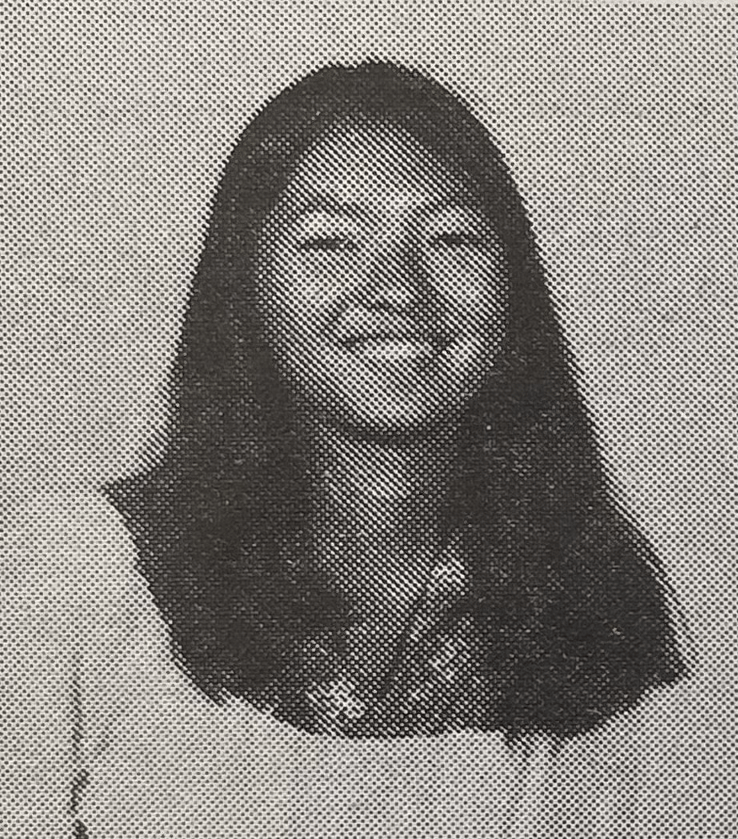

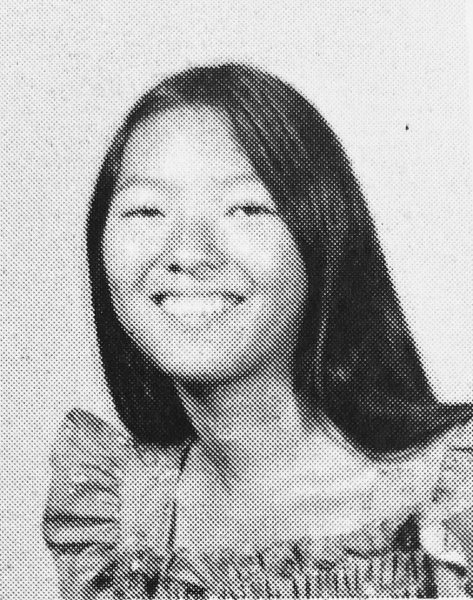

Friends of Momohara told The Pinion that she was shy but warm, with a gentle presence. Her closest friend, Jan Koehler (c/o 1978), who first met her at Washington Intermediate (now Washington Middle School), recalled that she often wore a bright smile.

When Koehler began to get to know Momohara, she noticed that, at times, she would become quiet and unsure of what to say. To break the ice, Koehler would imitate comedians to make her giggle. As their friendship grew, they spent more time together, visiting each other’s homes and getting to know one another’s families.

“She was always a very happy person with a pretty smile,” Koehler said in a phone interview with The Pinion. “She had that kind of laugh, where once she started, everyone else would too.”

The Pinion has reached out to possible relatives of Momohara, though no response has been received.

Koehler said Momohara loved to wear long muumuu dresses and was highly determined in her studies, particularly excelling in math. She was focused on her academics, driven to succeed, and not the type to prioritize relationships.

“She didn’t skip classes or do [drugs]. She wasn’t the type of person to make out with boys, period. Not happening,” Koehler said. “She was the kind of person who was always going to make something out of her life.”

Lorna Soong (c/o 1977) first met Momohara through her older sister, Faye Momohara, and the two often walked to school together. In a text interview with The Pinion, Soong described Momohara as “sweet, kind, and thoughtful.”

At McKinley, the high school junior’s circle of friends mainly consisted of members of the McKinley Theater Group. Among them was Tam Anderson (c/o 1979), who was a sophomore when she first met Momohara. Anderson recalled how the group would quickly eat in the cafeteria before heading to W123, the drama classroom in what was then known as the English building, to spend the rest of their break.

“We’d just have fun, running little improvisation games, you know, just doing skits,” Anderson said in a phone call interview with The Pinion. “It was fun and carefree. Everyone was laughing.”

“[Dawn] was just starting to really enjoy it,” Anderson added.

Although Momohara wasn’t a member of the organization, she became close friends with many of its members and had hoped to get involved in their productions. Koehler, who was the vice president of the theater group, recalled how much fun they all had together.

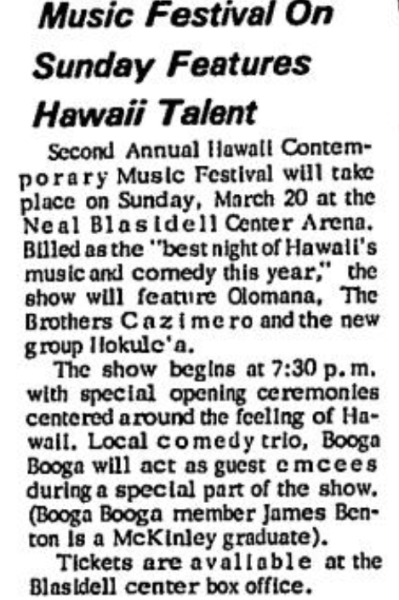

“One guy could do impressions of presidents, and the other could do Booga Booga,” she said. “We thought we were a mini-SNL cast.”

The Murder of Dawn Momohara

(By Dominic Niyo)

On Sunday, March 20, 1977, Momohara received a phone call from an unknown number. The details of the conversation remain unclear, but before leaving home that afternoon, she told her mother, Mabel Momohara, that she was meeting friends at Ala Moana Shopping Center, according to the HPD press conference.

As the hours went by and Momohara still hadn’t returned, Mabel became increasingly worried. Unsure who she might have been with, she contacted several of her daughter’s friends to ask if they had seen her.

“She had called my sister, Laura Mollring Sturges (℅ 1978), but we didn’t have plans to see her that weekend,” Anderson said.

Later that night, around 10:30 p.m., Momohara’s mother called the police to report her daughter missing. HPD classified her as a runaway juvenile, which was standard procedure for missing teenagers at the time.

The following day, March 21, 1977, a Monday, Soong arrived at Momohara’s home early, expecting to walk to school together. However, when she arrived, Mabel didn’t mention anything about her daughter being missing.

“I was only told that she would not be at school that day,” Soong said.

Just before classes began, at 7:30 a.m., a teacher discovered a lifeless body in the second-floor hallway of the W building. The teacher immediately alerted the administration, and the vice principal contacted the police.

Authorities arrived shortly after, sealing off the area with yellow tape and preventing students from entering as they began their investigation.

Koehler, who had arrived late to English class that morning, was stopped by police at the entrance. As she stood outside, she overheard whispers from other students—rumors that a girl had been found dead upstairs.

“We didn’t know what was going on,” she said. “We were standing in the grass, not knowing what to do.”

One by one, the students outside the building were pulled aside by the police and asked if they knew a girl named Dawn Momohara.

“I told the police I knew her, that she was my friend,” Koehler said.

Momohara’s body was found lying on the floor, directly above the drama classroom where she and her friends often spent their lunch breaks. Her green muumuu dress was in disarray, and an orange cloth was tightly wrapped around her neck.

The medical examiner later determined that she had died from asphyxia due to strangulation, as indicated by the marks on her neck. Injuries consistent with sexual assault were also found, along with several of her belongings, including her blue shorts and underwear that both contained seminal fluid.

Later reports from the Honolulu Star-Advertiser in 1977 stated that her body had been discovered eight to 12 hours after her death.

A Case Unsolved for Decades

Koehler burst into tears upon hearing about Momohara’s death, but despite her grief, she felt a strong sense of responsibility to help. She was among the first to speak with detectives and the press, providing vital insights into Momohara’s life, personality, and the circumstances leading up to her disappearance.

“Knowing [Dawn], she wasn’t supposed to go. It wasn’t her time,” Koehler said. “And if she was in a compromised situation … when she was struggling to stay alive, I think she would’ve probably just screamed really loud.”

“She had a lot of life to give,” Koehler added.

The school’s campus is made up of multiple buildings, each designated for different subjects. While classes remained in session that day, students scheduled to be in the W building were kept out by police. Word quickly spread across campus that a girl’s body had been discovered in one of the buildings.

“I heard some teachers say that a girl had died, and it was a rape and murder,” Soong said. “I was scared, but didn’t talk about it the rest of the day.”

It wasn’t until later, after she returned home from school, that Soong heard on the radio that the girl found on campus was Momohara.

“I was in shock and crying,” she said. “I couldn’t call her [family] and express my condolences. I was shaking so much.”

Anderson found out about Momohara’s death on Monday night when the police contacted her, asking if she had been with her recently. Having been sick over the weekend, she didn’t know where her friend had been. The following day, Anderson returned to school to find a community engulfed in grief.

“It was very solemn,” Anderson said. “You could feel the sadness, even from those who didn’t know her personally.”

“Just the fact that it happened on campus, to a fellow student,” Anderson added.

The circumstances surrounding Momohara’s presence on the second floor of the W building remain a mystery. McKinley is located west of her home on Elm Street, with Ala Moana to the south. No direct route to the shopping center required passing through the campus.

“The witness had a police scanner,” Det. Kaio said. “He said it was part of his routine to drive through campuses and check for people hanging around, knowing they weren’t supposed to be there.”

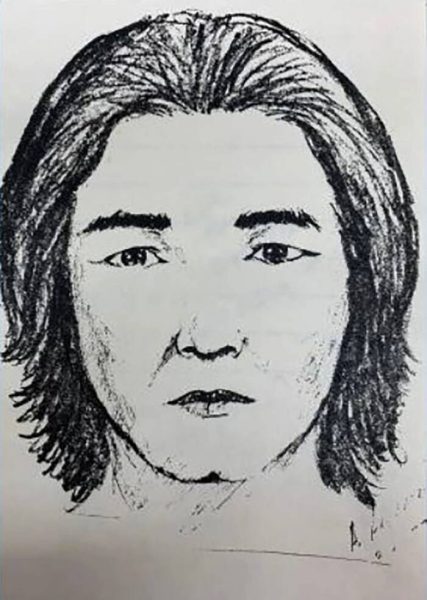

By the time the witnesses circled back, both the man and his vehicle had vanished. They later provided the police department a definitive sketch of the suspect and his vehicle.

As detectives retraced Momohara’s final days, they interviewed several individuals who may have had connections to her. Among them were Gideon Castro (c/o 1976) and his older brother, William Castro (c/o 1972), both of whom claimed to have regularly talked to her on the phone.

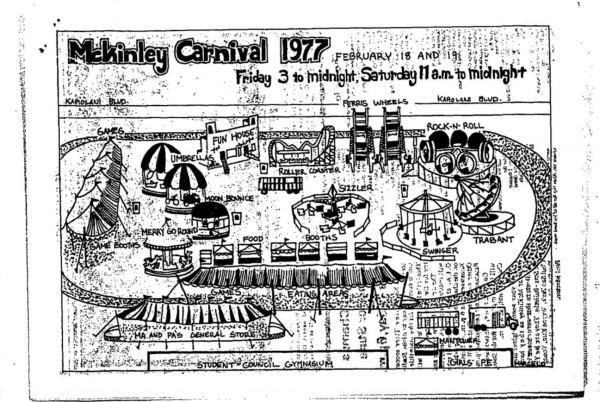

On March 28, 1977, investigators interviewed Castro, who was later identified as a suspect in the case. He told them he had met Momohara at a school dance during the 1976 school year and that she would occasionally call him while he was still a student. Their last conversation, he said, was at the McKinley Carnival in Feb. 1977, where they spoke briefly. He recalled mentioning that he had recently returned to Honolulu after serving in the Army Reserve.

That same day, detectives also spoke with his brother, William, who said he had met Momohara through Castro at the same 1976 dance. He denied having dated Momohara but acknowledged that they had spoken on the phone a few times. He recalled their last encounter three days before her death when she passed by his house. They had a short conversation, during which he offered her a ride to school, but she refused.

The suspect’s sketch was later released to the public, but it did not lead to any significant breakthroughs in the investigation.

“Her death has haunted me for years,” Anderson said. “These things don’t happen to people you know.”

In the days after Momohara’s death, Anderson recalls teachers advising students—especially female students—to stay in pairs and exercise caution, as the suspect had not been identified. The uncertainty surrounding the investigation created a tense atmosphere on campus, heightening awareness and concern among students.

“I was unable to sleep at night for a few days after Dawn was found,” Soong said. “I had to go to the doctor to get Valium pills.”

The school administration later installed gates on all buildings with open staircases, which are now locked after school hours. Additional lighting was also installed to improve security.

With few leads to follow, the investigation stalled, and the case remained unsolved for decades. Throughout the years, rumors of hauntings began to circulate among students. Though not as widely discussed today, ghost stories became an urban legend on campus, with accounts of eerie occurrences in the hallways and restrooms of the W building.

Recent Investigations

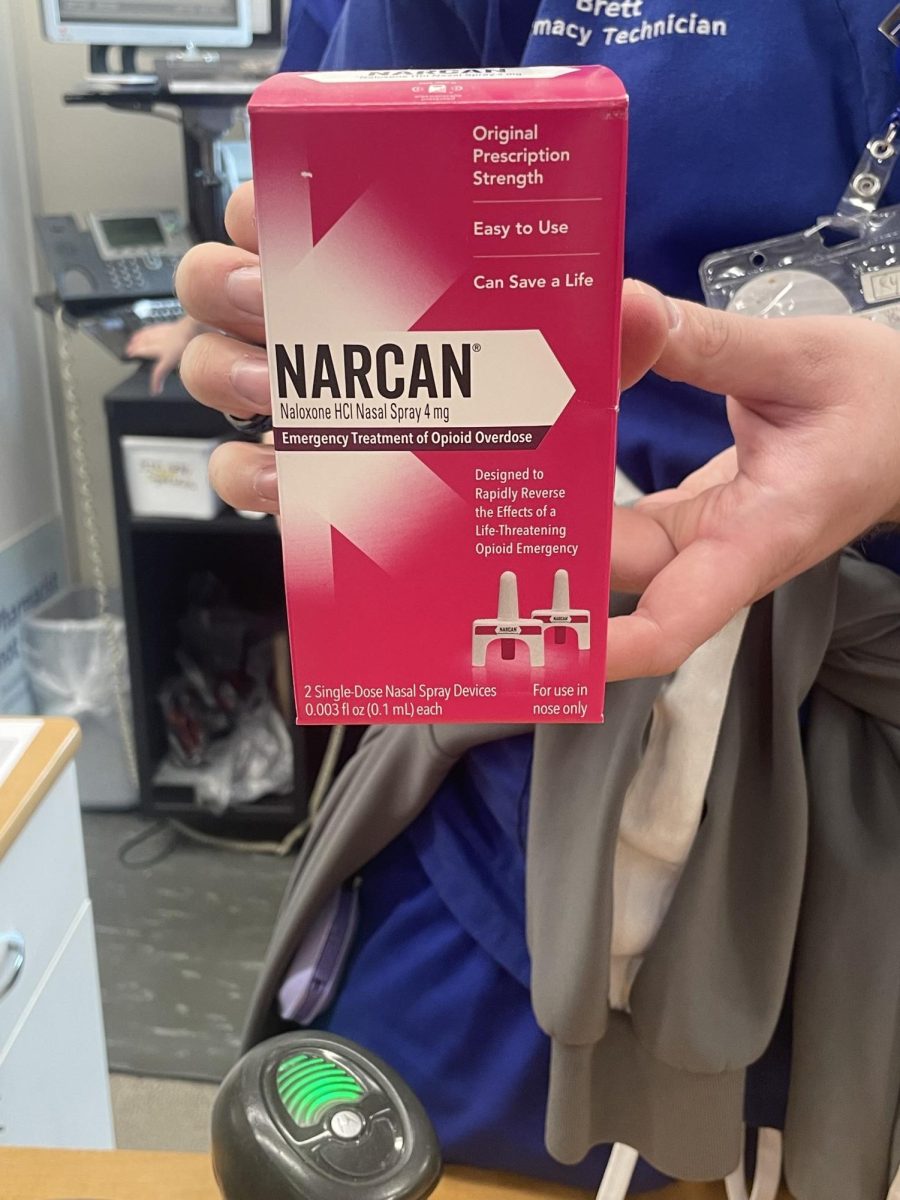

In March 2019, cold case detectives reopened the investigation into Momohara’s murder as part of their ongoing efforts to reassess unsolved cases. Detective Michael Ogawa, who was then overseeing the case, requested DNA testing from the HPD Scientific Identification Section’s Forensic Biology Unit on key items, including Momohara’s shorts and underwear recovered from the scene.

Although DNA technology was not readily available at the time of the original investigation, HPD had preserved all materials.

“Our priority is the evidence,” Lt. Theommes told The Pinion in an interview at HPD headquarters. “We focus on [extracting] DNA from old cases and use genetic genealogy to help with investigations. Cold cases are really difficult when key evidence or witnesses are no longer available.”

The results, returned in May 2020, revealed a DNA profile from an unidentified male. Detectives checked national and state databases, but there was no match. During this time, they also reached out to Koehler to follow up on her statements to the police from 1977.

“Dawn and I were members of a Socials club called Moonlight Memories,” Koehler said.

The Socials were school-sanctioned, student-led organizations. Moonlight Memories, an all-girls club, regularly organized social events with other all-boys Socials from nearby high schools.

“I started going through all the boys that we met at these different Socials and thinking if anyone stood out,” Koehler said.

Due to the 2020 pandemic, detectives informed Koehler that further DNA testing was delayed because of funding issues and shutdowns that affected the process.

By June 2023, Detective Kaio took over the investigation. In Sept. 2023, further DNA analysis led detectives to a familial match to William Castro, pointing to a new lead in the case.

“After reviewing the initial detectives’ reports, I realized they had interviewed [him]. Once I confirmed it, we began investigating him further,” Det. Kaio said. “We had to conduct a lot of research, which eventually led us to discover that he lived in Chicago, Illinois.”

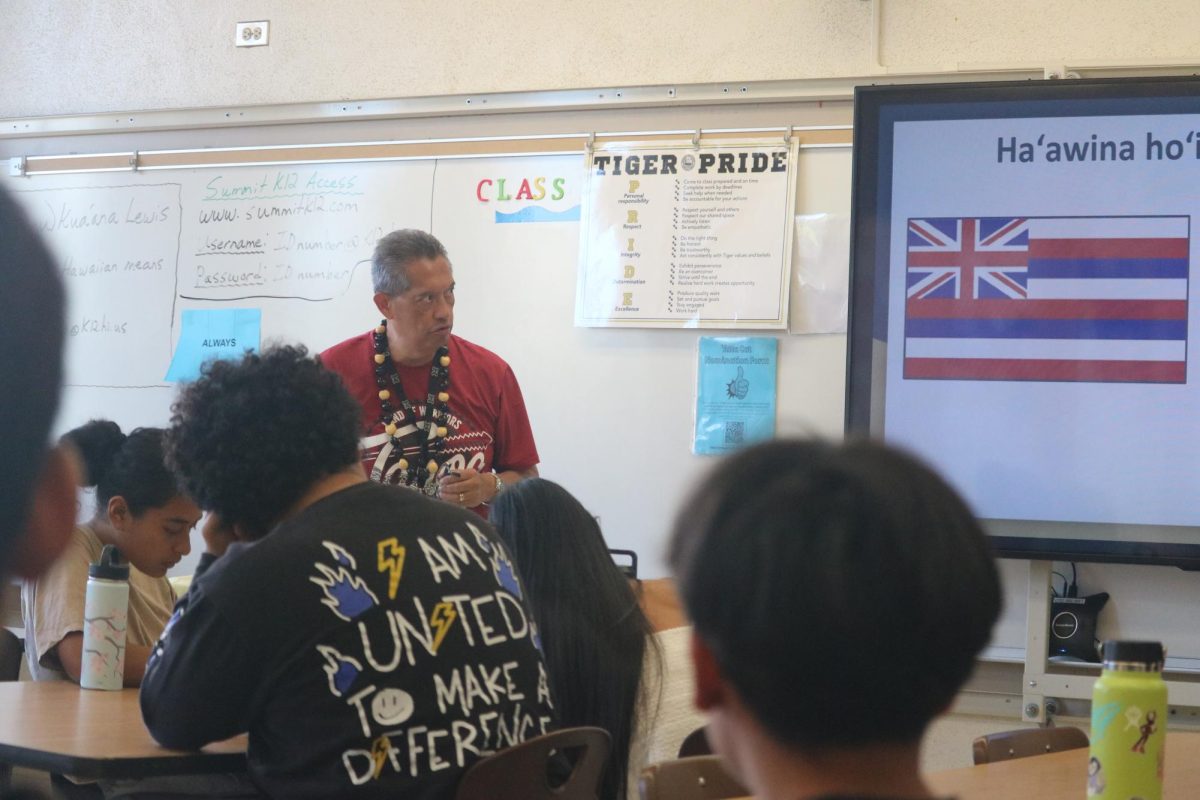

School librarian Sandy Domion first learned about Momohara’s death when Detective Kaio visited the campus library in late fall of 2023.

“He mentioned that he was working on a cold case and wanted to look at the school yearbooks,” Domion said. “I believe he didn’t find what he was looking for.”

Detective Kaio later discovered that the Black and Gold Yearbooks contained no record of either Castro or William. The Pinion also reviewed the yearbooks but found no record of either individual.

School records also indicate that Momohara was a junior at the time of her death, contrary to the HPD’s earlier statement during the press conference claiming she was a sophomore.

By Nov. 2023, members of the Homicide Strategic Enforcement Detail traveled to the Chicago area to assist in surreptitiously obtaining a DNA sample from William’s biological child. They were successful in acquiring the sample from a discarded item.

“We sent the sample back to our lab, and after testing, they confirmed there was no match to the unknown male from the samples collected in 1977,” Det. Kaio said. “At that point, we had to go back to the drawing board and shift our focus to [Castro] and conduct further investigation into him.”

Through further research, it was revealed that Castro lived in Utah at a nursing facility and had a biological child living in a different state. With assistance from the FBI and Homeland Security Investigations, authorities were able to locate the child and obtain a DNA sample surreptitiously.

After initial analysis by the FBI, the sample was sent to HPD for further comparison. The test results confirmed that the child was a biological offspring of the unidentified male whose DNA was found at the crime scene.

In early Jan. 2025, detectives from the Homicide Strategic Enforcement Detail traveled to Utah to obtain a surreptitious biological sample from Castro. Once in hand, the sample was sent to the HPD DNA criminalist for comparison with the previously unidentified male’s DNA profile. The results were definitive: the DNA obtained from the evidence matched that of Castro.

“I’m doing this for Dawn, first of all, and her surviving family members,” Det. Kaio said. “There’s no greater pain than losing one of your loved ones and not knowing what happened to them or gaining any resolution to who did it.”

Authorities arrested Castro at the nursing facility, where he was 66 years old and bedridden due to several medical conditions, including paralysis, acute respiratory failure, and a history of sudden cardiac arrest. Detectives attempted to collect another DNA sample with his consent but were unable to due to his condition.

Both Anderson and Soong were shocked when the detectives made an arrest, each saying they did not know Castro.

“We never forgot Dawn,” Anderson said. “[Our friend group] were amongst ourselves, feeling happy and knowing that our friend was finally getting the justice she deserved. Justice for Dawn.”

Although Koehler didn’t personally know Castro either, she remembered Momohara mentioning him in their conversations and noting that he lived near her house. Koehler said she never expected the suspect to be a fellow McKinley student, especially someone who was outside their social circle.

“I never thought it would’ve been one of us,” Koehler said. “She was always careful about who she spent time with.”

“I thank the police department for never giving up on Dawn,” Koehler added.

Following Castro’s arrest, prosecutors in Honolulu faced complications that hindered further progress in the case. According to prosecution officials, challenges with a key witness and the current state of the evidence led to the decision to request the temporary dismissal of the charges. A Utah judge granted the request, releasing Castro but allowing for the possibility of re-filing charges in the future.

“For the extradition and the trial, I wouldn’t be able to give a timeline just because of his condition. Not only will the flight be taxing on him physically, it’s also about the logistics,” Det. Kaio said. “If he’s brought here without proper care, we risk something happening to him.”

The Pinion reached out to Castro’s court-appointed lawyer, Marlene Mohn, but has received no response.

Koehler expressed disappointment with the decision to release Castro, noting that it was frustrating given the progress made in the case. She hopes he will eventually confess to the crime.

“We’ve already waited 48 years,” Koehler said. “The truth is all we want to know.”

This story was originally published on The Pinion on March 13, 2025.