Sophomore Laila Alkhatib is at home with her family when she hears the sudden explosions of fireworks — or so she thinks. In reality, they are gunshots fired into the air by a 45-year-old man having a mental health crisis. After barricading himself in a car, he threatened to shoot himself and any first responders that arrived. Alkhatib watched as her neighbors flooded out of their houses to investigate the noise. Police cars, a drone, and the St. Charles Regional SWAT team arrived to deescalate the situation, but after the man made a threatening action toward an officer, SWAT officers fired at the man and he was taken to a hospital for his injuries. Alkhatib was shaken by this incident, and was especially worried for the safety of her friends in the area.

“I was surprised because I feel like I don’t live in a neighborhood where that kind of thing is common,” Alkhatib said. “I have friends in the area and I [was] worried about them, I texted and made sure they were okay. I wasn’t worried for my safety [but] I was worried about them [and] parents and other people were worried about the safety of their children.”

This violent scene stirred up the St. Charles neighborhood, but many people outside of the neighborhood never knew it happened. On the news, it was lost in a sea of headlines — news on four completely separate shootings, car crashes, court cases, and a fatal hit-and-run. All of this was published on First Alert 4 within 24 hours of the gunfire in Alkhatib’s neighborhood. The local media is oversaturated with horrifying reports, and national media is no different. School shootings appear in national headlines all too frequently, shocking and disturbing the nation — for a week. Then something comparably horrifying takes its place, and old tragedies will gradually fade from the nation’s memory. The sheer quantity of school shootings in recent history has taken away from the original disbelief that used to accompany them, as Alkhatib explained.

“I’d always hear stories about school shootings, but you know, I feel like I’m not really surprised by them anymore,” Alkhatib said. “Like, it’s kind of the norm.”

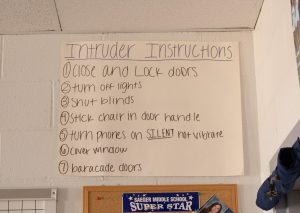

Alkhatib is not alone in feeling desensitization to this type of violence. Students in the Francis Howell School District are accustomed to intruder drills, having participated in at least one every year since elementary school. However, as senior Thomas Masterson pointed out, many students’ understanding of the drills has changed since elementary school.

“Back then, I really didn’t know what was going on,” Masterson said. “They just said, ‘Get in the corner and sit down.’ But now [I] understand what’s going on and it’s a common occurrence.”

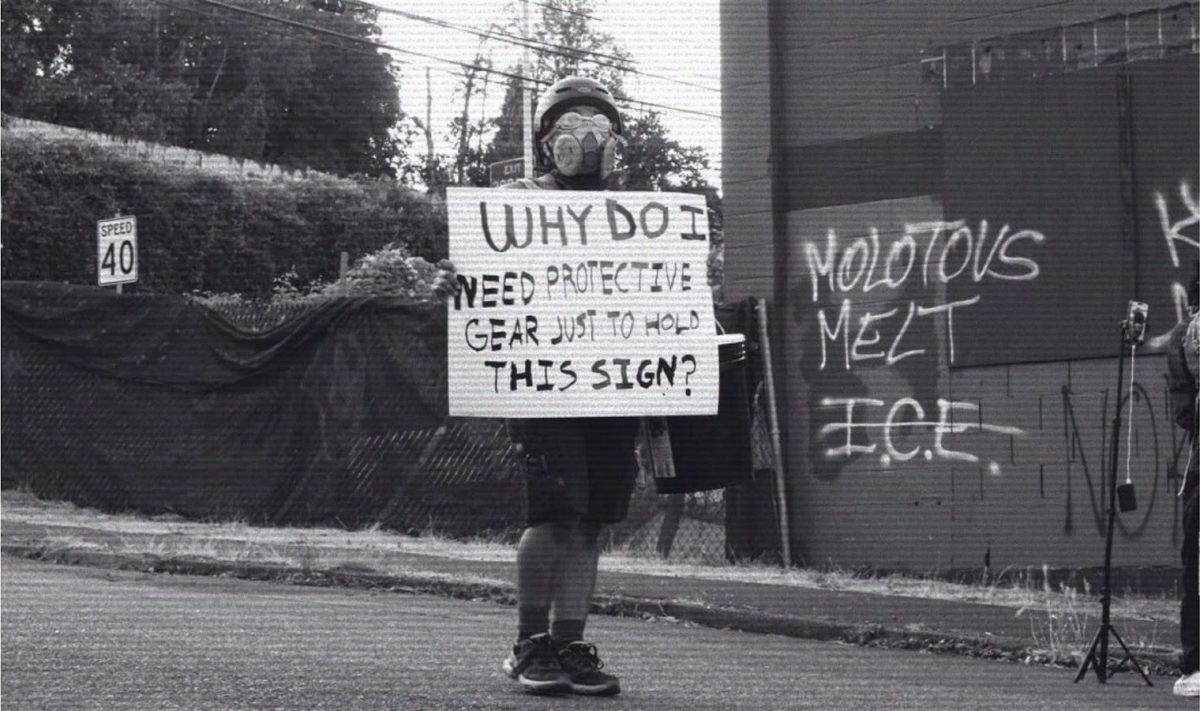

The bigger picture is teenagers’ across-the-board desensitization to violence. They see it everywhere: social media, news, video games, movies. Death and violent themes permeate teenage society — high schoolers joke about murder and suicide regularly. “Oh, she’s dead,” they threaten after getting cut in the lunch line. “I’m gonna kill myself,” they say after hearing about tomorrow’s math test. These are meant as jokes, but they have a detrimental impact on teens’ perception of the value of life. Murder isn’t a joke, it’s an atrocious crime. And suicide is a leading cause of death among teenagers — casually tossing around suicide threats trivializes the weight of a serious problem.

The trivialization of violence is heightened by the content that teenagers consume through social media, news and movies. Violence and violent language is becoming more common in movies, even those geared toward young audiences. Junior Jordan Zambrzuski is a horror movie enthusiast. The violence and gore in these movies used to bother her, but she’s grown used to it. Zambrzuski doesn’t believe her desensitization to violence in movies carries over into her life, but she noted it might for some people.

“People see violence on the screen [and] get used to seeing it,” Zambrzuski said. “It normalizes it… I think for some people it could carry over into real life.”

When death is represented only as a “destined to die” character in a horror movie or a kill count in a video game, it creates a habit of glossing over death. When people see a headline in which 100 people die, will they consider those people’s lives as well as their deaths? What about their families? Their aspirations and favorite foods? These people are now part of a statistic rather than a member of humanity.

Movies and hallway jokes seem innocent enough, but they contribute to a larger culture of desensitization to violence. Even when a man was shot in Alkatib’s neighborhood, she stopped thinking of it within days. Perhaps this is an indication of how violence has seeped into every corner of our culture: news, social media, movies, even jokes that are meant to be harmless. Would a teenager who took death and violence as a serious matter last long in this culture? Maybe not. Feeling the emotional impact of every death around the world as if it were the death of a close friend or family member would leave a person in psychological shambles.

But there’s a place in between this extreme empathy and the current apathy around death and violence– people should strive to live in this “in between” place. Part of this is being aware of the content they consume, especially for teenagers. Teenagers who are aware of the content they consume and how it affects their thoughts and actions will be better off than those who, however unintentionally, expose themselves to unnatural violence until it seeps into how they perceive life and death.

This story was originally published on FHC Today on April 11, 2025.