Editor’s Note: This article contains material of a highly sensitive nature, including topics such as mental health, self-harm, suicide, kidnapping, and violence.

They fled danger, thousands of miles from the only home they’ve ever known, with nothing but the clothes on their backs. They lost family and friends along the way. After obtaining newfound legal status, they learned how to survive in a new environment, with a new language, new customs, and systems. They were finally safe. Now it may all be stripped away by a new administration.

This is the nightmare that Afghan refugees across the country, many of whom previously worked for the U.S. military and embassy in Kabul, are now facing: having their protected status stripped away and being deported back to a country run by terrorists, where chances are they will not receive a warm welcome back.

They helped our country and were subsequently forced to flee to the U.S. for safety. Most of the refugees would much rather still be at home in Afghanistan with their loved ones, familiar culture, and lifestyle.

“The United States was in Afghanistan fighting a war, and recruited these people to help them as translators, security guards, soldiers,” Dita De Leeuw, a volunteer for the refugees, said. “That’s why they’re here now and we’re not taking care of them.”

De Leeuw has been a driving advocate for this cause, working with the 50 Afghan refugee families living in Skokie, Illinois, for the past few years, as well as coordinating other volunteer efforts. She has worked tirelessly to help these refugees in all aspects of life: from getting an education to obtaining driver’s licenses, government papers, and medical care, to finding jobs and homes.

She hopes to do all she can to support these families and help the children, especially girls, grow up in well-adjusted households with as many opportunities as possible. Women in Afghanistan aren’t able to get drivers licenses, jobs, or even read. Here, girls can grow up knowing they are valued by society.

De Leeuw is in the process of creating the infrastructure for a local nonprofit organization called ROYA, named after one of the little Afghan girls, and also meaning “dream” in Farsi. The organization is mainly working to support Afghan refugee families who have resettled in the Chicago area, and has recently obtained 501-C3 nonprofit status, making it operational Monday through Sunday, as the website and funding remains in the works.

“The goal of ROYA’s support is to pick up where relocation agencies leave off. We aim to empower families by enhancing their skills and capabilities, enabling them to build a hopeful future for the entire family,” De Leeuw explained. “This is more about kind and gentle hand holding, being a friend in need to these families. There are a lot of daily questions and issues that come up for them.”

Before Trump began his second term, refugees entered the country through relocation agencies such as Refugee Run, Heartland Alliance, Ethiopian Alliance of Chicago, and many more. Typically, support for refugee families from these organizations lasts between three to six months. The services then drop the families, leaving them on their own without additional guidance.

This assumption of independence is unrealistic for a lot of families, many of whom come from less educated backgrounds without access to basic academic resources, who need years of support until the kids are old enough to manage things like finances and documentation.

Regardless, as we have seen, these services are now out of commission because the Trump Administration has stripped all funding from them. It is unclear yet whether it is solely for his spending waste removal strategies to improve the national deficit, or if it is meant to deter refugees from staying.

This topic hits close to home, as I work as an English as a Second Language (ESL) tutor for a family, whom I will refer to as the G’s for their safety, who fled Afghanistan and came to the U.S. in 2021 under Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) from the Biden Administration.

I tutor their daughter, whom I will call S, in reading, speaking, and writing, as well as basic math properties and help with additional social skills. She is around 14 years old—I say around because none of them have birth certificates and the Islamic Hijri calendar is different—and is one of the sweetest people I’ve ever met.

Their whole family is warm and welcoming, always putting out snacks like nuql (sugary almonds) and sweet green tea when my father and I come by, and trying to send us home with naan and other traditional foods, despite the fact that they live below the poverty line.

While I sit with S, my father is often on the phone with the government, trying to help the family pay various bills or complete certain documents. It is a frustratingly tedious and rigid process—difficult to get past the automated recordings and extensive tele-holds.

S speaks some of the best English out of their whole family. Short, simple strings of words with misplaced conjugations here and there make up their conversations. Their father barely speaks any and sends voice memos to my father, but they are often jumbled and hard to understand. He has a job at a factory, and has worked a few other jobs here and there like driving Ubers, in order to make ends meet.

Currently, he is trying to get his green card, but is having a lot of trouble. He previously worked for the U.S military in Afghanistan, however when he went to his interview to graduate from refugee status to a green card two years ago, the language barrier and difficulty in tracking dates complicated matters. The interviewer fixated on the fact that he used to work with weapons and in conditions of war instead of the normal, more typical citizenship questions.

While he attempted to explain his story via the interpreter, dates and information became mixed up because many documents were left in Afghanistan. The G’s may have had a marriage certificate at one point, which is crucial in getting their green cards, but they aren’t able to understand or articulate what happened to it.

There’s often a lack of cultural sensitivity in these types of high-stress situations, which makes it hard to bridge the gap to understanding. Two years and a whole other interview later, many of the refugees have their green cards, and he still does not. De Leeuw and my family are working closely with Illinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky’s office to expedite the process.

Education has also been a prevalent barrier in their communication. Dari, the language most of the refugees speak, is native to Afghanistan, specifically Kabul. The G’s are Pashtuns, coming from the province Paktika, a more rural province of Afghanistan where they speak both Dari and Pashto.

Mr. G’s education ended in middle school after his father died, so he went to work and then joined the army early on in his life. Because of the conservative nature of the area and its connections to the Taliban, Mrs. G was never able to learn to read or go to school.

Because of this, their family is behind a lot of the others in assimilating, and are sadly looked down upon by many of the other refugee families who are more educated and come from places in Kabul. It is the classic city mouse versus country mouse on a grand scale. Not only are they experiencing racism and a lack of cultural sensitivity from Americans, but they are cruelly shunned by their own community.

To make matters worse, the community of Afghan refugees in the U.S. is significantly smaller than most other refugee populations. Ukrainian, Indian and other groups of refugees have had time to build large communities across the U.S., but because of the influx of Afghan refugees over the past couple years and the lack of support for them, there is not that same sense of unity.

The 50 Afghan refugee families that live in Skokie all have different situations and statuses. Some are here via SIVs, some on basic Temporary Protective Status (TPS), and some have green cards. Regardless of their status, the efforts of the Trump Administration to punish and deprive these refugees is clear as day.

Not only has the government been unreliable in terms of support and efficiency towards citizenship, but it has been declared that going forward, Afghan refugees who have been under TPS, will be subject to deportation, taking effect beginning on May 20.

This is a result of, as of April 2025, U.S. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem concluded that Afghanistan no longer meets the statutory requirements for its TPS assignment. TPS, may I remind you, is a humanitarian immigration status granted to individuals coming from places deemed too dangerous to return to. While it is currently unclear what will happen to refugees of more advanced statuses, our country has seen that nothing is off the table at this point.

Afghanistan is ranked by the U.S government as a Level 4 on the danger scale, meaning “do not travel [there] at all costs.” The country is riddled with terrorism and violence, gripped by the tight fist of the Taliban. The U.S Embassy in Afghanistan was forced to suspend operations in August 2021, eliminating all emergency assistance from the U.S. government to U.S citizens stuck there.

Even though they are physically safer now on our soil, most of the refugees still have family and friends in Afghanistan, and it is heartbreaking for them to hear about the violence back home. The Taliban have gone after their loved ones, blackmailing them for money just because they hate their connections to the U.S.

On Sunday, April 27, a young 20-year-old woman, Abida, who was still living in Afghanistan and was friends with one of the female refugees in Skokie, committed suicide by burning herself to death. Her family was being threatened by the Taliban, who took her brother and father hostage, trying to kidnap her and force her to marry one of the member’s brothers. She felt she had no other choice than to end her life.

According to the Wilson Center, approximately 80% of all suicide attempts in Afghanistan are made by women. Additionally, reported depression and anxiety rates have grown steadily for women over the past few years. Regardless of where they live in Afghanistan or how conservative they are, no women or even families are safe from the Taliban’s restrictions and threats. One family now living in Skokie recounted to De Leeuw how the Taliban used to hang bodies up on their street to keep them in line.

Mr. G formerly fought for the U.S military in Afghanistan and fled with his wife and five children after his brother was kidnapped. Their choices were to escape to the U.S, speaking about three words of English and not having any preserved documents, or to possibly meet the same fate as his brother.

Even so, he was harassed by the Taliban for ransom money even after making it to the U.S. People recognize on a basic level that Afghanistan is extremely dangerous and systematically oppressive, but what they don’t realize is that these refugees physically cannot go back now, it puts them in immediate and overwhelming life-threatening danger.

Every day, despite the G’s resilience in the face of unimaginable adversity, they struggle to make ends meet and communicate with this contrast of western society. Three of their kids are old enough to go to school now and are on financial assistance for every resource. Despite that, they still play like all kids do, joining after school activities like track and field. The family lives in a two-bedroom apartment and are constantly berated by their neighbors for the noise and mess they cause.

About a year after coming to the U.S, their mother found out she was pregnant once again. Now they have another adorable little girl, making up a total of six children. However, because their daughter was born in the U.S. and President Donald Trump’s previous order to end birthright citizenship was blocked by the federal courts of three states, if the family were to get deported, as of now their daughter would stay. The Supreme Court has heard Trump’s full case and now needs to make their decision.

Leaving a two-year-old child in a foreign country where almost everyone is a stranger is every parent’s worst nightmare. And yet, much of the situation that these Afghan refugees are put in is a living nightmare. When the first group of Afghan refugees escaped to the U.S. in 2021, one 15-year-old girl, B, was left behind by herself.

B’s family was attempting to flee to America one day at the end of August 2021. There was an explosion at the airport, and B’s mother got injured. B panicked and accidentally ran the wrong way, and got separated from her family, who went to a medical facility at the airport.

They were loaded onto a cargo plane, and reassured that they would reunite with her eventually in the U.S. In the chaos, her sister lost her shoes, and traveled without them until a stranger in Germany gave her some. That day at the airport was the last time they ever saw B.

De Leeuw worked tirelessly over the last four years to bring her here and reunite her with her family, but when Trump became president and blocked her scheduled refugee migration to the U.S., all of the work was for nothing. She was luckily able to get her I-730 form approved in December and received a passport, but still has to be given immigration approval, which is even less likely now. B, who is now 18, had been praying to be reunited with her family for three years, had her dream ripped away by a two-second presidential signature.

Her family members now take antidepressants and attend therapy sessions for the trauma they’ve gone through. They are completely dysfunctional and severely disorganized, her siblings feel immense survivor’s guilt for having better opportunities than she does. B goes in and out of communication with them, shutting them out and shifting between hope and despair, straining all of their relationships. It is hard for the family to be curious and experience the new opportunities of America because they are still emotionally tied to B.

This is one of the reasons I love teaching ESL to the G family: they are so curious and so willing to learn and grow. S is always so excited to talk about new words and ideas every single time we work together, more so than anybody else I’ve ever met. In the U.S., she can forge her own path, and despite certain financial or legal obstacles, she has opportunity and knows that her future is bright.

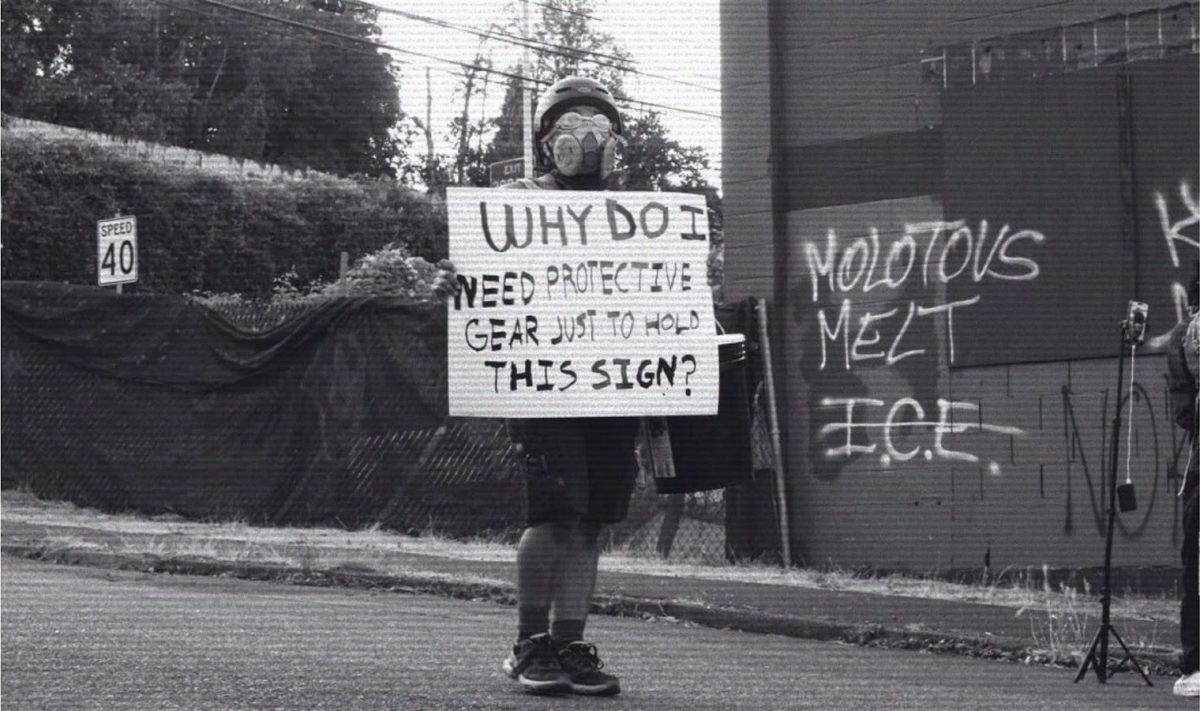

My question is, what happened to the U.S. being a country of opportunity? What happened to it being a melting pot? There’s a big difference between implementing better border security that weeds out violent and dangerous illegal criminals, and kicking out optimistic families who came here legally and did exactly what our government encouraged them to do. The hypocrisy is loud.

The new administration is showing foreigners that even if they do things the right way in order to come here, they will keep getting kicked while they are already down, time and time again. This is not a legality and safety issue anymore. This is about fighting deep-rooted prejudice and reinstating principles of basic human empathy.

“These Afghan refugees need to feel seen as human beings and have American friends,” De Leeuw said. “Period.”

This story was originally published on New Trier News on May 16, 2025.