“That’s racist.”

A complex phrase that has a plethora of stories behind it. So many people of different races have experienced some form of racism, whether that be through insults, bullying, or threats. Historically, people of color have faced racism extensively, as laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and, most notably, the Jim Crow Laws aimed to segregate and put down such people.

Now, racism is prevalent everywhere, as more people crack jokes targeting all races, such as Caucasian, Black, Asian, and Hispanic people.

According to Pew Research, 65% of people in the United States say it has become more common for people to express racist or racially insensitive views. This trend has become a norm in society and has even been treated as a joke on popular social media platforms such as Instagram.

Racism has not just been confined to social media, however. The United States, a country built upon freedom and inclusivity, fosters a multitude of remarks regarding people’s race in many places, one of them being schools. These remarks do not just target people of color; they have become more generalized to attack other minority groups such as the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities, and many others.

Despite schools being a place of learning and community, institutions in the U.S. have been infested with bullying cases.

However, a closer look at private and public schools can reveal the distinction between how each responds to bullying.

The result of ignorance: a public school’s reaction towards bullying

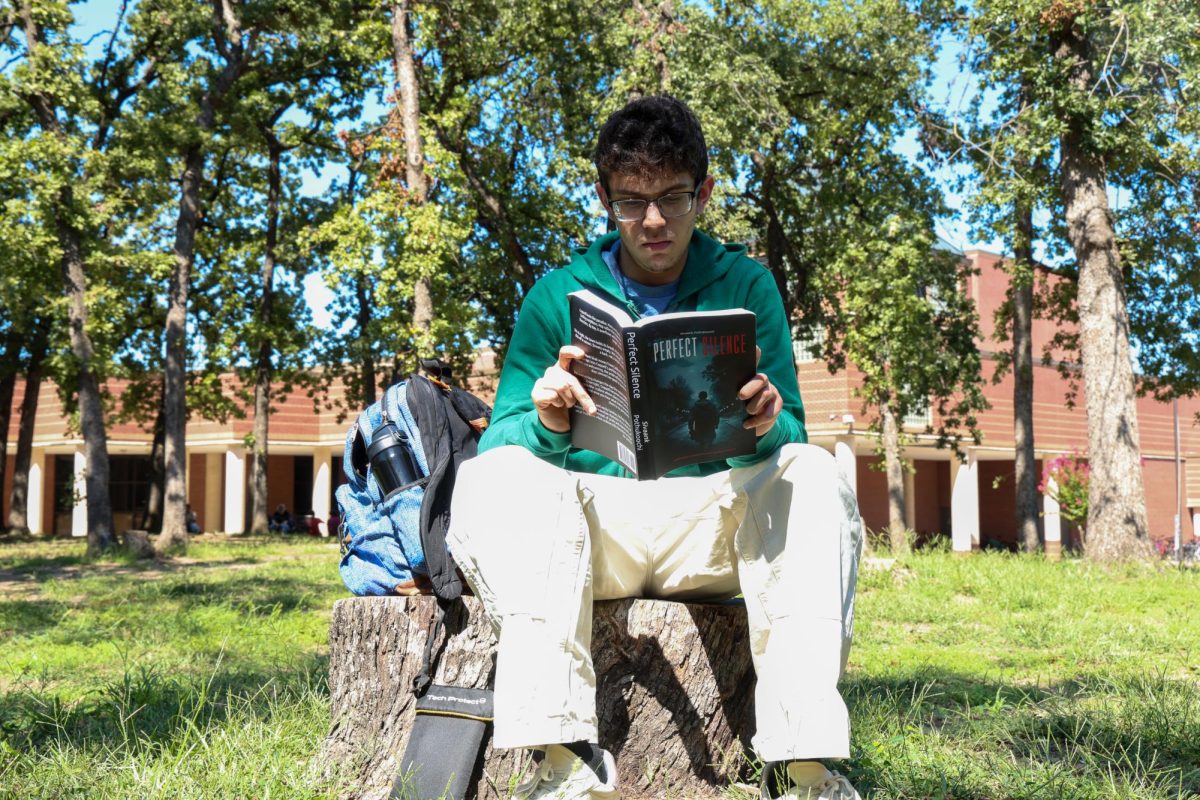

Ashwini Peruri, currently an internal medicine physician, experienced frequent bullying during her time at Spreckels School, a public school in California, which started as early as third grade. Sometimes it would be making fun of her, like calling her names, and other times it would be saying inappropriate comments to make her uncomfortable.

“The school bus was one of the worst places for me because going to and from school, the kids used to talk about me being brown, made fun of my name: ‘Ashwini-burger, Ash-Wienerschnitzel,’” Peruri said.

Racial interpellation is the act of assigning a specific title to a person, oftentimes in a derogatory way, to make fun of one’s race.

According to “A Case for Inclusion: A Study of the Relationship between Students of Color in Private Progressive Institution” by Aasiyah A. Ali, “an interpellator, a person who enacts racial interpellation to another, will create a differentiation between himself and the subject of his attention that brings to reality the deeply inherent racial caste system that exists between them.”

While racial interpellation is a definitive reason for racial bullying, it isn’t a solution to it, as shown in Peruri’s case. She constantly got called names, but the teachers never stepped in to help.

“Schools are on the side of not doing anything and not getting involved. Because a lot of times they’re hoping, ‘this will just blow over,’ or ‘we’ve got enough to worry about,’ or ‘this is a home problem,’ but it isn’t,” said Nicole Vidalakis, a licensed clinical psychologist.

Ever since the creation of free public schools, minorities have dealt with great forms of racism, some even going as far as to reject education from the subgroup.

Spreckels School was no different. At the time, it was a primarily white and Hispanic public school. Since Peruri was the only Indian, she bore the brunt of the bullying.

“I wasn’t Mexican and I wasn’t American in a predominantly Hispanic and white school. So I think I was the only Indian,” Peruri said.

A school climate is described as the “quality and character of school life,” according to the National School Climate Center. According to “Racial Equity in Academic Success: The Role of School Climate and Social Emotional Learning” by Tiffany M. Jones, Charles Flemming, and Anne Wilford, “numerous studies across grade levels have documented differences in perceptions of school climate based on students’ race, with students of color generally reporting worse school climate compared to white students.”

A bad school climate additionally leads to a power imbalance between white people and people of color.

According to “Seeing Like a Racial State: The Census and the Politics of Race in the United States, Great Britain and Canada” by Debra Elizabeth Thompson, “race is clearly more than supposed biological differences or state-derived modes of classification. It is encompassed in ideas and ideologies about how society should operate and how social order should be maintained, animated through many and varied practices and relationships of power.”

As illustrated, people of one race inherit power and utilize that power through the dominance of people of other races.

“When I look at some of the school districts that have mostly Caucasian and very few children of other races, the dominant race becomes significantly teasing, insulting, and telling the other children that they really are not very smart and they should go somewhere else,” said Dhara Meghani, a licensed psychologist in the School of Nursing and Health Professions Clinical Psychology Psy.D program at the University of San Francisco.

Peruri never told any adult about her bullying issue. Even still, she always felt as if the teachers knew about her situation; however, they never did anything to try to fix it.

In fourth grade, the bullying got so bad that Peruri started to skip school by faking stomach aches. Her mom vividly remembers the confusion she felt as her daughter constantly had these stomach issues.

“I didn’t know anything. I thought it was medical problems, stomach aches; she was complaining so much,” said Vijayalakshmi Ashokkumar, Peruri’s mother.

It was Peruri’s sister who first noticed her suffering and convinced her parents to move her to a private school for her middle school years. After further consideration, her parents decided to make the switch to a school called Santa Catalina in California.

During her time in Santa Catalina, her bullying experience decreased drastically. Peruri recalls only one incident in which she got teased.

“We were playing flag football, and a kid called me a ‘fudge-stickle’ because I was brown and a stick. I didn’t tell anyone, but somehow the teachers found out,” Peruri said.

Rather than ignoring her, the school faculty initiated an assembly about how name-calling was unacceptable. After that, the bullying stopped.

The money that follows: the incentivisation of bullying

Peruri’s case is not rare, as many people have experienced something similar. Even now that people have become more accepting of others’ differences, bullying is still very prevalent and is still being treated the same.

According to “Litigating Bullying Cases: Holding School Districts and Officials Accountable” by Adele Kimmel, “approximately 75% of the time that children get bullied at school, no adult intervenes.”

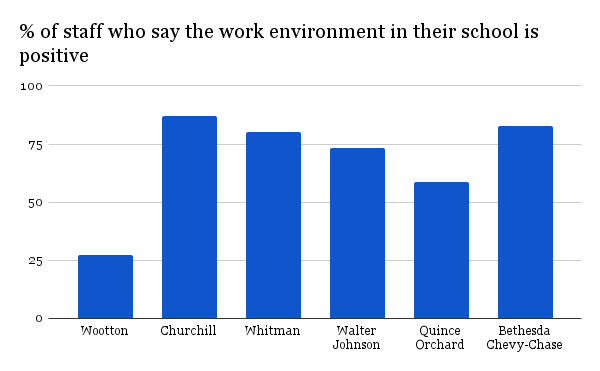

Along with that, in public schools, another factor that seems to slow them down when it comes to resolving bullying is resources. Since public schools do not require money from the families sending their children to the school, that means their funds come from the government and from donations.

“For example, if there is a school with a 200-student body, they would hardly have a part-time social worker, whereas in a private school with the same number of students, they may not even have a social worker, but their teachers are trained to a lot of aspects of the children’s behavior,” Meghani said.

However, according to the Education Data Initiative, the nation provides 12.6% of funding towards public education, well under the standard of 15%.

On the contrary, private schools do have an incentive to take care of their students because of the money they are getting paid. According to an article by Chrissy Kapralos, private school tuition is on average $15,000, and tuition is around 52% of the revenue they make.

“Parents kind of think, my child can be babysat by the school instead of public school. In theory, paying for a private school to give your child more tools and skills,” Vidalakis said.

Therefore, the percentage of bullying occurring in private schools is about 5.5% less than what it is in public schools, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

Economic differences aside, Peruri still reflects on her childhood and is very grateful for the environment switch. She appreciates the people around her who stood up for her when she couldn’t and is glad that her parents’ decision was not in vain. She is glad that more people were vocal about bullying in her private school so that she could heal from all the hardships she had to endure in primary school.

“I think I’d actually just tell myself, none of this matters. They can say and do whatever they want. It’s up to me to give them power by acknowledging it,” Peruri said.

This story was originally published on Scot Scoop News on September 17, 2025.