From the colorful flyers lining Carlmont’s hallways to the specialized programs beyond campus, extracurriculars promise passion, growth, and belonging. But for many students, those opportunities come with a price tag that puts them just out of reach.

Sports team fees, arts program expenses, and Advanced Placement (AP) exam costs make activities that are advertised as open to all feel far less accessible. These opportunities often shape students’ identities, from the thrill of athletics to the creativity of the arts, yet behind the laughter on the field and the music in the practice rooms lies a quieter reality: some students simply cannot take part.

The result is a divide: while many at Carlmont can stack their resumes with multiple activities for college, others are left with fewer options. This inequity not only affects individual students but also reflects a broader national conversation about fairness in education.

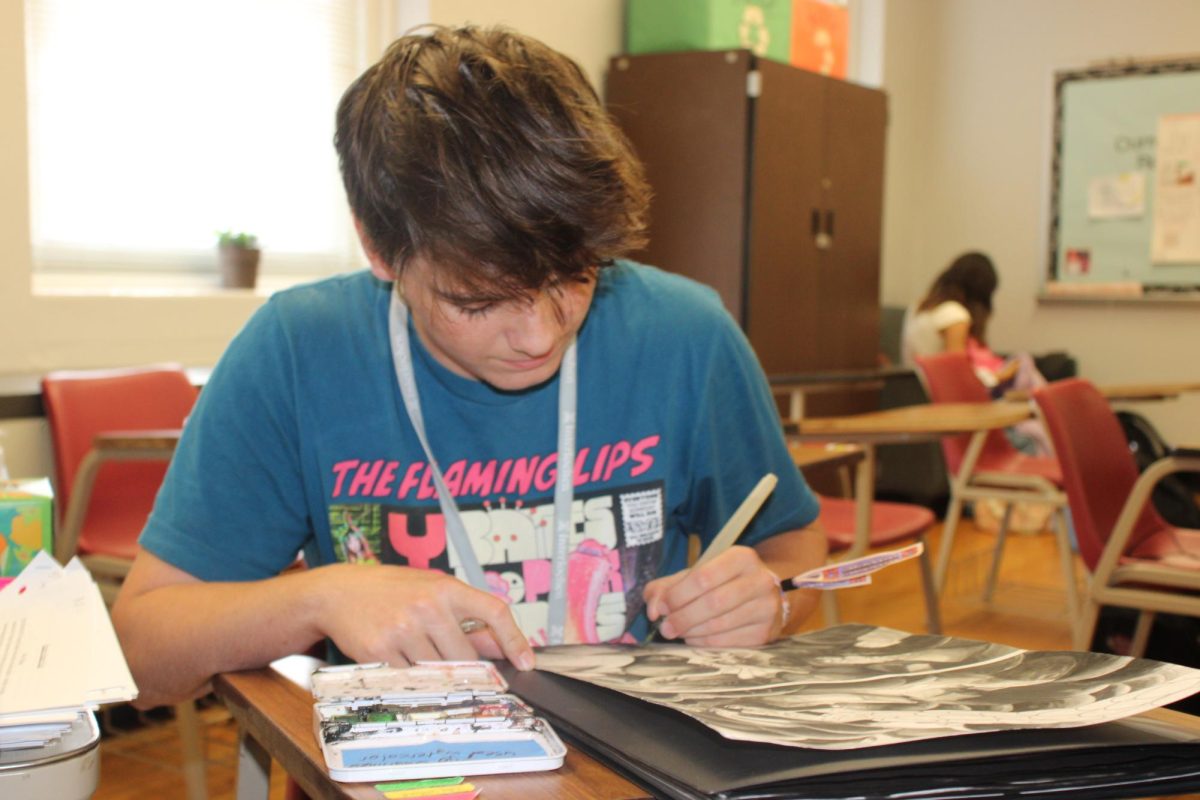

Michelle Peng, a junior at Carlmont, who had been taking art classes for several years, said she had to step away from something she loved when her family’s finances became a challenge.

“When I realized I couldn’t take art classes anymore, I felt very empty and depressed. I even felt a bit of hopelessness, because I feared that without my teacher’s guidance, I would not be able to produce quality art,” Peng said.

Uniform fees, instrument rentals, competition travel, and supply costs quickly add up. While some students can absorb these expenses, others are left out, missing opportunities that build skills and connections.

According to a straw poll of 120 Carlmont students, 28.3% said they had decided not to join or continue an extracurricular activity because of the cost.

At Carlmont, administrators recognize that fee waivers and support systems exist, but not all students know how to access them or feel comfortable asking. The survey also revealed uncertainty: 65% of students were unsure whether Carlmont provides enough financial support, while 12.5% said support was lacking and only 22.5% felt it was adequate.

“Socioeconomic differences are some of the things I have noticed when it comes to the people who can access certain extracurricular activities. Sports such as fencing, rowing, squash, and equestrian are considered expensive due to equipment and sometimes travel costs, making them less accessible to people without as much financial flexibility,” said Amy Kim, a junior at Carlmont.

National data reflect this same trend. Studies show that students from lower-income households are significantly less likely to join extracurricular activities due to financial barriers. In California, while public schools cannot charge tuition for activities, indirect costs such as travel, uniforms, or materials still add up quickly.

At Carlmont, many activities depend on fundraising and family contributions to cover these expenses, leaving students to weigh passion against price.

A student’s story: creativity limited by cost

For Peng, the price of pursuing her passion in art became unsustainable. Her experience shows a challenge that some students face: extracurriculars can provide growth and community, but financial barriers often determine who can participate fully.

“Each hour of art was around $70, and it was just too much. Art supplies are super expensive, so I couldn’t afford to buy good-quality paint or canvas. So now, I can only rely on my old supplies and my iPad. It’s hard to watch others continue doing activities you wanted to be a part of, even when you’re working just as hard,” Peng said.

Pursuing her passion for art became increasingly difficult as her family faced financial instability. The costs of materials, supplies, and classes added up, creating pressure that extended beyond finances to her creative development.

“My mom might be starting her own business since she doesn’t have a job right now. She previously worked at a pharmaceutical company, but ended up quitting. My dad writes books, but because he hasn’t published anything yet, our family doesn’t have a stable source of income,” Peng said.

Without structured lessons, Peng’s confidence began to waver. The absence of structured lessons left her uncertain of her own skills.

“I began fearing failure, as I was on my own now, and all the supplies I needed had to be bought and paid for from my own pocket. I literally could not afford to paint a bad painting, because I would waste materials,” Peng said.

Her family’s financial situation meant she had to make tough choices, cutting back on more than just art. These limitations show how extracurricular costs can affect not only learning but also emotional well-being.

“My family isn’t quite on a budget for living yet, but I quit all of my extracurricular classes to save my parents’ money. They like to save, and my extracurriculars, especially the classes, were less necessary than other house expenses,” Peng said.

Though Peng’s future plans remain stable, financial realities still influence her decisions and narrow her opportunities, affecting which programs she can pursue.

“My family’s financial situation won’t affect my plans for the future much, but it did add a little limitation on what programs I would choose and what schools I would be able to attend. My parents assured me that they have enough money for whatever I do for my education, but after knowing that my family doesn’t earn a stable income anymore, I still wish to save as much as I can for them, just in case there are medical emergencies,” Peng said.

Peng hopes school leaders will recognize how finances quietly shape student potential and limit opportunity, since participating in extracurriculars often depends on more than just talent and hard work.

“In this current economy, I hope everybody, especially the district leaders, understands that there are families out there that cannot afford to pay for their children’s education and interests. The families try their best to support their children, but the financial burden just won’t alleviate,” Peng said.

One solution, Peng believes, would be greater transparency around costs, helping students and families plan ahead rather than being blindsided by “invisible charges.”

“I would eliminate ‘invisible charges’ in extracurricular activities. Extracurricular programs should list every single payment that parents are responsible for, or just fund everything,” Peng said.

Peng’s situation isn’t unique. While some students continue extracurriculars without worry, others like her are forced to step back, missing opportunities that build skills and confidence.

How access shapes aspirations

For Kim, money has not been a concern for her extracurriculars. Since many of her activities happen outside Carlmont, Kim said finances didn’t change her sense of belonging or opportunities at school.

However, Kim acknowledges that not every student has that privilege and sees how expensive opportunities, especially academic ones, can create unfair advantages.

“There is definitely a preference for people who do extracurriculars outside of school in terms of educational potential. Cost and access change a student’s path beyond high school, especially when applying to college or research camps, which can be expensive and unavailable for students and families who don’t have the financial flexibility to make it happen,” Kim said.

These differences often appear in subtle but powerful ways, shaping how students see their futures and what opportunities they feel within reach. Students with greater financial support can access additional programs and experiences that not only develop skills but also build résumés for college and careers, while others are left with fewer options.

“I do notice differences between students who can afford activities and those who can’t. Those with the financial means are often better off, and many talk more confidently about their future plans. Expensive extracurriculars give them advantages — like access to summer programs, internships, or recruiting opportunities — that directly influence their aspirations at Carlmont and beyond, whether that’s in college, academics, or future occupations,” Kim said.

For Kim, fair funding is important. Schools need to distribute resources thoughtfully so all students can participate. When money favors certain programs or students, challenges form for those in less popular or costly activities.

“I am not an expert on how Carlmont funds their extracurriculars, but I would like to say that Carlmont should try to divide their funds equally for all sorts of extracurriculars. Spending a majority of their funds on a certain activity and leaving less for others would create an unfair advantage to the activity, team, or students receiving larger proportions of Carlmont’s funds,” Kim said.

Carlmont’s response to equity concerns

Carlmont administrators recognize that cost can be a hurdle for some students, but say that support systems are in place to help families when necessary.

“The school is supposed to cover the cost of extracurricular activities for students if they cannot afford it. Many families opt to pay for whether it’s a field trip or a sport, but to participate in an extracurricular school-sanctioned activity, the school pays for students if they cannot pay themselves,” Carlmont Administrative Vice Principal Grant Steunenberg said.

Carlmont also leans on booster clubs and community support to bridge the gap.

“For instance, sports boosters raise money. They assist students within and teams with student costs. The Carlmont Academic Foundation (CAF), music boosters, and all booster organizations raise money not only to buy equipment, jerseys, instruments, and things like that, but some of that money that they raise can also be used to offset the cost for students who can’t afford it,” Steunenberg said.

Still, Steunenberg said that some activities are more costly by nature, forming barriers despite available support, which affects more than participation; they impact belonging and identity.

“Anytime a student feels they can’t participate in an activity due to financial reasons, it has a dramatic impact on their well-being. There’s a sense of being ‘less than’ compared to peers who can afford outside lessons or club sports,” Steunenberg said.

Another problem is that public schools’ resources vary compared to private schools, which can limit the opportunities they can fund.

“Private schools are funded through tuition and boosters, often from wealthier families who are willing to pay for top-tier equipment, uniforms, and travel. Public schools rely on tax revenue and don’t have the same ability to provide those experiences,” Steunenberg said. “What public schools can offer often depends on the community. Some communities can donate more, which allows for better experiences. Carlmont is in a fairly fortunate area, so our families can contribute extra toward students’ activities,” he said.

The broader equity picture

For Lindsay Pérez Huber, a professor of equity, education and social justice at California State University Long Beach (CSULB), financial barriers in extracurriculars cannot be separated from systemic inequities.

“Many public schools in California, especially in urban areas like Los Angeles and Oakland, serve predominantly students of color from working-class families. Most of our public schools are highly segregated, and so when we think about the intersection between race, racial background, and socioeconomic status (SES), those are typically very much tied together in our state because of the high level of segregation,” Huber said.

However, cost is only part of the equation, as limitations can also be tied to family obligations.

“It is not only costs, but also time. So many students from working-class families are taking care of siblings while their parents are at work, or they’re working to help support their family. So there is really limited time for students to participate, aside from the financial burden,” Huber said.

The consequences ripple into academics and identity, affecting how they perform in class.

“The more engaged students are in extracurricular activities, the better they do academically and feel a greater sense of belonging. Students who don’t have those opportunities have a lower sense of belonging — not feeling that place is theirs,” Huber said.

Activities requiring equipment or travel tend to hit hardest, leaving some completely shut out since networks often form around teams and shared activities.

“A new bat is $300. If a family doesn’t have $300 to spend on a bat, that means that your child doesn’t have a way to participate in the sport,” Huber said. “If the team has to travel and go to another city or to a championship out of state, that family has to afford gas, hotel, and food.”

For students of color, microaggressions can make participating even harder.

“Besides the financial burden, for students who don’t feel comfortable on campus or feel like they belong, they’re less likely to want to become involved. Unfortunately, research shows that our Black and brown students often face forms of microaggressions at their high schools, based on racialized perceptions of who they are,” Huber said.

Schools are trying innovative ways to help all students participate. Initiatives like lending equipment and helping cover travel costs make sure everyone has a fair chance to join, regardless of income or background.

“Some schools are starting to do equipment loan-out programs, others earmark district money for sports or academic programs. It really comes from administrators who understand their community and think about creative ways to support students,” Huber said.

From policy to participation

Students like Peng aren’t alone in feeling priced out. Sequoia Union High School District’s (SUHSD) Education Services division also recognizes the issue. Elizabeth Chacón, Assistant Superintendent of Education Services, said financial challenges can limit participation and deepen inequities. Schools often step in to cover costs so students can still access activities that build leadership, teamwork, and confidence.

“In SUHSD, we do everything we can to provide support that opens doors for our many students whose participation in some activities may otherwise be limited,” Chacón said.

Still, costs can quickly create opportunity gaps if left unaddressed.

“Without support for things like fees for AP exams, sports equipment, or club dues, it is possible to widen opportunity gaps for students. In SUHSD, we provide financial support to ensure that opportunities aren’t limited to only certain students in order to avoid these disparities,” Chacón said.

District strategies include free lunches, waiving or reducing AP exam fees, providing equipment for athletes, and ensuring that dances and other events are accessible regardless of cost. Partnerships with PTAs, school foundations, and community organizations also help ease expenses, particularly for students from lower-income households.

“Sequoia Union uses a mix of strategies, like supporting fundraising that benefits entire teams, groups, and clubs of students. Schools continually work with community partners to ensure no student is excluded from participating if they want to,” Chacón said.

One of the district’s most effective policies has been AP exam fee reductions, which have made advanced courses more accessible for many families. In athletics, uniform and equipment assistance has also removed barriers for students who otherwise may not have been able to participate.

“These efforts have helped more students join, enjoy, and stay engaged in various aspects of our school communities,” Chacón said.

SUHSD helps students obtain work permits and explore careers if they choose this path in addition to or instead of extracurriculars, and helps them build skills through work experiences.

Looking forward, Chacón said it is important to keep students informed so they know help exists.

“Keep communication clear and supportive so students know that financial help is available. SUHSD already makes strong efforts to reduce barriers, and continuing to expand those supports — whether through fee waivers, scholarships, and partnerships — ensures that every student can explore their interests without worrying about cost,” Chacón said.

Beyond the balance sheet

Extracurriculars are more than hobbies, they are pathways to self-expression, belonging, and opportunity. But when hidden costs push students out, the consequences extend beyond participation.

At Carlmont and across the country, financial barriers to extracurriculars are quietly shaping whose voices are heard, whose talents are nurtured, and whose futures feel possible.

Schools face the challenge of ensuring that all students, regardless of income, can fully participate. For now, Carlmont is working to bridge the gap, but the voices of students make it clear: access to opportunities shouldn’t come with a price tag.

Steunenberg said that while the district provides some funding, it often isn’t enough to cover all costs at the level students need to fully participate. Steunenberg said that meaningful change must extend beyond Carlmont to the entire district.

“If we had the genie in the bottle that could grant us a magic wish, it would be enough money to cover all extracurricular activities. The district does provide some funds, but we often only cover the bare minimum so that as many students as possible can participate,” Steunenberg said.

This story was originally published on Scot Scoop News on September 22, 2025.

![Senior Dhiya Prasanna examines a bottle of Tylenol. Prasanna has observed data in science labs and in real life. “[I] advise the public not to just look or search for information that supports your argument, but search for information that doesn't support it,” Prasanna said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_0073-2-1200x800.jpg)