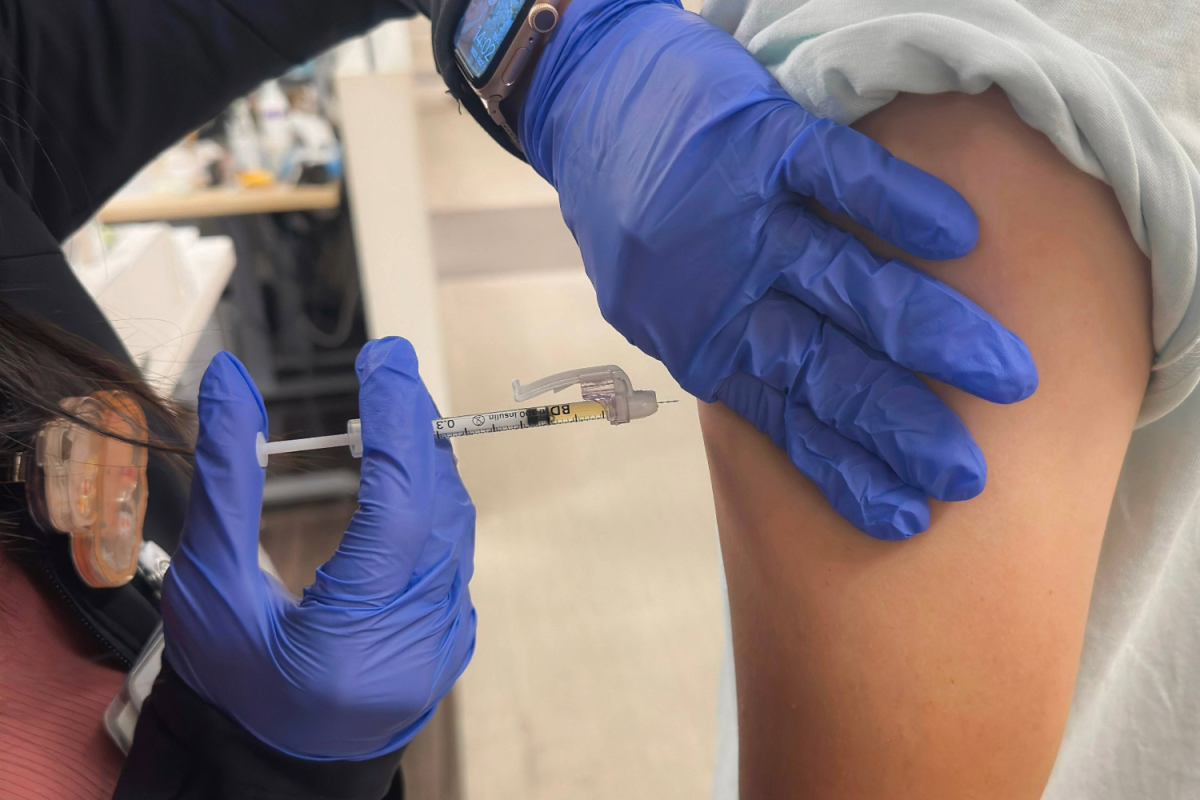

Four West Coast states, including California, issued a joint recommendation on who should be vaccinated for winter respiratory viruses, announcing it as a counterbalance to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s own guidance, which they say President Donald Trump has compromised in politicizing.

That same day, Sept. 17, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill (AB) 144, granting California authority to base future vaccine guidance on recommendations from credible independent medical organizations, rather than relying on the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

Yet the debate over federal vaccine and health policy is not new.

The vaccine argument

Catherine Flores is the executive director of the California Immunization Coalition, a nonprofit committed to achieving full immunization across California to prevent the spread of infectious diseases and their long-term health outcomes.

“Since the beginning of time, when diseases were ravaging communities, people were just treating what happened and sort of dealing with it,” Flores said. “Fortunately, thanks to science and discovery, people figured out that creating vaccines and preventing disease was a far better way to go.”

Vaccines have been around for over two centuries, ever since the world’s first vaccine started saving millions of lives from smallpox. Today, most people never have to see the devastating effects of once-common deadly diseases like polio, measles, and rubella — a success story, but also part of the problem.

Flores remembers how, growing up, diseases like smallpox felt like ancient history — something distant and no longer a threat. However, the sense of security that comes with this generational distance has led to a dangerous complacency in many.

“When I was a kid and I saw pictures of smallpox, I was deathly afraid, but I was very relieved when my mother told me, ‘No, that’s gone now.’ Similarly, measles and chickenpox are gone for most people, and polio is gone, so the impact of vaccines is substantial,” Flores said. “You’ve probably heard the phrase: ‘We’re a victim of our own success.’ Because people don’t see these diseases much anymore, they don’t think their vaccines are necessary, but that’s not true. Take COVID-19, for example: even though we keep trying to get rid of it, it’s going to keep coming back, and so is the flu, so we need to keep up with our vaccines.”

Despite this, many continue to argue that there’s no need for vaccination simply because they never get sick, according to Dr. Karen Suskiewicz, who has been an internal medicine physician at Sutter Health for 17 years. This overlooks the fact that vaccines were designed to protect not just individuals, but entire communities, a concept known as herd immunity.

“The first thing everybody thinks of is that vaccines help prevent disease in you. If you get vaccinated against measles, you are very unlikely to get measles,” Suskiewicz said. “But it also helps with herd immunity. If I vaccinate you, then you’re not able to get the disease and pass it on to someone else. So, the more people to get vaccinated, the less likely a disease will be able to spread throughout a community, which also reduces the risk of passing on the disease to those who are more vulnerable.”

Not everyone can be vaccinated. Some individuals have medical conditions that prevent them from receiving immunization, while others don’t respond fully to it, so they rely on the immunity of those around them to stay protected.

“It may not be that you’re worried that if you get the flu that you’ll get very sick, but I’m worried about someone you come across who’s more vulnerable, who could get sick and pass it on to someone else,” Suskiewicz said.

Suskiewicz also warns that dropping vaccination coverage doesn’t just increase individual risk; it also puts more pressure on the already fragile healthcare system.

“One of the big things that happened with the first part of the pandemic was that the medical healthcare system got overwhelmed by the number of people who were sick,” Suskiewicz said. “If we stop encouraging vaccines in everybody, we could have another large wave of COVID-19 infections or other infections. We won’t have the staffing, the support, or the infrastructure to support that.”

New controversy: politics or public safety?

While the CDC has faced political pressure in the past, the governors of California, Oregon, Washington, and Hawaii argue that the Trump administration has brought an unprecedented increase in interference, calling it an assault on science.

“I feel like it’s a very political issue because, generally, the right is anti-vaccine and the left is pro-vaccine,” said Carlmont junior Sequoia Leger. “The fact that the CDC has completely flipped because of a newly elected president is emblematic that it’s a very biased source at the moment.”

In response, the four governors formed the West Coast Health Alliance (WCHA) earlier this month, which has chosen to release its own vaccine guidelines after finding it impossible to ignore the recent actions of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

“The current secretary of the HHS, Kennedy, is a longtime anti-vaccine activist who’s lived in California,” Flores said. “When we passed vaccine legislation in California, he was right there, front and center, to combat it. He and his network of supporters believe that vaccines are not a good choice, and now, he has the ability to implement his vision and his ideology on the largest scale possible.”

In the past few months, Kennedy has dismissed all 17 members of the ACIP — a panel that plays a key role in shaping national vaccine policy and insurance coverage — and replaced them with cherry-picked appointees, including several vaccine skeptics, according to the WCHA.

“I was surprised. We thought that Kennedy would make sure that other persons who aligned with his ideology would be appointed, but we didn’t think that he would just fire them all,” Flores said. “That was probably my worst week because we know how good these people are with how their backgrounds are vetted, and how much integrity, education, experience, and knowledge they have. To have all of those people not only dismissed, but their reputations also demeaned in public by saying that they were compromised and beholden to the pharmaceutical companies, was really appalling.”

However, this move, while alarming to many, is not entirely unexpected from Kennedy, who, prior to his appointment, was affiliated with organizations such as the Children’s Health Defense, an organization widely criticized for supporting and spreading anti-vaccine misinformation. During this time, he repeatedly promoted widely debunked claims, most notably the false link between vaccines and autism.

“There’s science involved, and there’s sociology involved, and there’s study involved, but these administration officials don’t have this background,” Flores said. “That’s why our public health network is alarmed about how these persons in leadership positions are saying things that are outside of their area of expertise.”

Adding to the controversy, Kennedy also recently fired CDC Director Susan Monarez, just 29 days into her tenure. Montarez, who testified before Congress on the same day the WCHA issued its new vaccine guidance, said her dismissal came after she refused to comply with Kennedy’s unreasonable demands, including pre-approving all future vaccine recommendations and terminating career scientists without cause. Her removal has triggered a wave of resignations from high-level and career CDC staff, who agree that Kennedy is compromising the agency’s scientific integrity.

Suskiewicz shares these concerns.

“I’m worried because I’ve seen a lot of turnover in the CDC, and it seems like they’re not getting the funding or the support from the government that they’ve gotten in past years. That’s worrisome to me because, as a physician, if someone asks me about a vaccine or something that I’m not familiar with, the CDC is always what I’ve turned to,” Suskiewicz said. “I don’t know where else I would go right now to get that information.”

The split: new recommendations

While the CDC has been scaling back its recommendations for who should receive the COVID-19 vaccine — not only no longer advising the shot for healthy children and pregnant women, but also making it harder for those who still wish to receive it by pushing for requiring a prior consultation with a medical professional — the WCHA has chosen to adopt the universal policy the agency previously supported.

Suskiewicz recalls the confusion and uncertainty that followed the CDC’s shift this past year and how they were addressed by the WCHA.

“Usually, at work, we’ll get updates about when we’re going to be getting our supply of flu or COVID-19 vaccines and what our policy’s going to be, but it was very quiet this summer. And then you read in the papers that the government is changing its policy on who’s eligible and who they recommend to get the vaccines,” Suskiewicz said. “I have a lot of patients over the age of 65, who have a higher risk if they get sick with the flu or COVID-19, and we’ve all tried very hard to stay vaccinated and stay protected, so it was very frustrating, until recently, to feel like I didn’t have much control over what the government was recommending. Luckily, that seems to have changed, at least here in California.”

Under the WCHA’s new recommendations, all children aged six to 23 months and two to 18 years with risk factors or no previous vaccination should receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Concerning adults, those who are 65 years and older, younger with risk factors, and planning pregnancy are encouraged to get vaccinated. Anyone in close contact with someone with risk factors is also advised to be immunized.

Importantly, the alliance emphasizes that the vaccine remains available to “all who choose protection,” regardless of age or risk level.

“What we’re saying is that, for any patients who are interested in getting a COVID-19 or a flu vaccine this winter, we are happy to give it to them,” Suskiewicz said. “And I fully support that. I want to keep all of my patients protected. I want to keep up the herd immunity.”

The WCHA also recommends that everyone six months and older receive their flu vaccines, and infants under eight months and adults who are 50 to 74 years with risk factors or 75 years and older get an RSV vaccine.

According to the WCHA, these new immunization guidelines follow those of trusted national medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Many of these groups have recently distanced themselves from the CDC after learning their guidance would no longer be considered in their decisions. As a result, they have also started to release their own recommendations for this vaccine season.

For the first time in 30 years, the AAP is not aligned with the CDC on vaccinations.

“The exciting thing is that we have all of the major medical associations really working together, and that should give the public some comfort and assurances that vaccines are going to continue to be safe and the recommendations continue to be solid,” Flores said.

Adding to the relief of many, these new WCHA recommendations and AB 144 have already made a visible impact. According to Suskiewicz, before Newsom’s recent actions, many medical foundations were unsure if they’d be able to provide vaccinations to everyone.

“We just got our supply of the COVID-19 vaccines, so I was just able to start vaccinating patients against COVID-19. We’ve had the flu vaccine, but we had been waiting for Newsom so that Sutter Health could order vaccines and feel comfortable with us administering them to patients,” Suskiewicz said.

One of the main concerns with the ACIP’s updated guidance was that, despite being only a recommendation, its federal status would make it risky for physicians to follow alternate guidelines, especially if insurance providers declined to cover vaccines not endorsed by the CDC. AB 144 directly addressed this issue.

“The bill did a lot of things, but, related to vaccines, it also required that insurance plans cover all of these vaccines. And then it also provided liability protections for healthcare providers who really needed that assurance that they would be protected under the law with the federal recommendations,” Flores said.

Still, the bill has its limitations. One of its most critical involves federal immunization coverage for vulnerable children.

“The challenge is the Vaccines for Children program, a federal program that pays for vaccines for children who are uninsured or underinsured in vaccine coverage,” Flores said. “We’re not sure what’s going to happen with that. That’s what’s scary for pediatricians right now, or anybody who’s seeing children. It’s a federal program, and the state law won’t impact that. So, we’ll have to wait and see.”

The shifting landscape of vaccine policies is not limited to the West Coast. Other states outside of the WCHA have also issued guidance differing from that of the CDC.

In particular, many northeastern states have formed their own coalition: the Northeast Public Health Collaborative, which has recently added its own COVID-19 vaccination recommendations to the conversation.

Meanwhile, Florida rests on the far end as the first state to suggest ending vaccine mandates for children, and is being strongly opposed by health organizations.

“That was another gutting day to think that somebody would do that,” Flores said. “Idaho and Louisiana are also areas of trouble. There’s a risk with doing away with mandates. It’s so loose up there now, too, so I don’t know why they think they need to get rid of mandates because people can just decline anyway, so it’s more of a political statement they’re making.”

As vaccine policies become more and more divided between states, the question is raised: are these divides permanent?

“I’m concerned that we’re going to have to continue to stay separate in order to continue to vaccinate patients. I hope we do whatever we can to vaccinate as many people as possible,” Suskiewicz said. “But I would not be surprised if recommendations in California and the West Coast are different from other parts of the country from here on out.”

Flores, however, sees a different path forward.

“I’m optimistic that once changes are made at the federal level, it will return to balance and overall protection, but I feel like this is also an opportunity. This experience has highlighted some weaknesses,” Flores said. “So, when we get back to balance, I’m hopeful that there’ll be some safeguards put in place to protect the organizations from being compromised like I believe they are now.”

Despite the uncertainty, Flores emphasizes that public health, not politics, must remain the priority, with the ultimate goal of protecting lives, not agendas.

“I think we can always rebuild,” Flores said. “We can rebuild organizations like the CDC, but we can’t get back lives, so that’s what we have to focus on: protecting lives to make sure children, adolescents, and adults don’t needlessly suffer from a preventable disease.”

This story was originally published on Scot Scoop News on October 3, 2025.