As Immigration and Customs Enforcement intensifies its tactics under the Trump administration, immigrant high schoolers face an unfamiliar pressure. Across the country, agents have appeared at extracurriculars, traffic stops, court hearings and neighborhood strolls, targeting non-citizens with limited legal protections. Agents have even entered private homes — sometimes using ruses or false pretenses to gain entry — leaving families terrified behind front doors.

This extension of enforcement reflects the reach of federal policies. Passed July 1, President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act endowed ICE with an additional $170 billion to secure the Mexico–United States border and oversee migrant flow. Since January, more than 1,000 deportation flights have occurred, with several viral videos documenting the arrests. Meanwhile, the president has pledged to deport one million immigrants per year during his term.

Prior to the OBBBA, in early 2025, claims of ICE trucks in Iowa City alarmed residents, and on Jan. 20, the Department of Homeland Security lifted arrest restrictions on schools. Although Iowa City Community School District superintendent Matt Degner reassured families Sept. 8 in an email that the district’s core value is “being all in for all kids,” the threat of deportation continues to rattle West’s student body. West has the second-highest minority enrollment of any high school in the district, after Tate High School, and such pressures force its most vulnerable groups to be on high alert.

At West, Victor Diaz Galindo, a Spanish teacher and Unidos club sponsor, aims to create “a space to welcome students of color or [students] with immigrant backgrounds.” As an immigrant with similar experiences to many Unidos students, Galindo is attuned to ICE’s public raids.

“Everyone’s hands are tied legally,” Galindo said. “It’s scary to think what we would do [if a student were deported]. The biggest thing I do is support who I can. I want to be a mentor for students [and] create a space for anyone to let their guard down. These small efforts make a bigger impact.”

While Galindo’s work may seem limited to classrooms, he sees the impact of immigrant communities far beyond instructional time.

“If it [weren’t] for immigrants, Iowa would be decaying. Iowa has stagnated in growth population-wise,” Galindo said. “Immigrants came in and made towns grow and flourish. West High [has] continued its growth because of international students, migrants and new populations that come in.”

Findings from the American Immigration Council suggest that immigrants are essential to Iowa’s economic vitality. In 2017, immigrants paid $390 million in state and local taxes and held $3.4 billion in spending power, representing a net positive for Iowa’s economic health.

Despite immigrant contributions, in April, the Pew Research Center found that 42% of Hispanic adults worry about deportation due to the administration’s policies. This anxiety also extends across multiple minority communities; for Black adults, the rate was 19%. Many West students also reflect this fear, particularly the school’s vibrant Sudanese population, including Student Government President Waleed Ibrahim ’26, the son of Sudanese immigrants.

“[Deportations are] horrible,” Ibrahim said. “There’s no reason for ICE to go to any high school [and] actively find people and deport them. As a community, city, state or nation, we have to shed light on how bad this is.”

At West, diversity is central to the school’s identity. Students come from dozens of cultural, racial and religious backgrounds, and many, like Ibrahim, see how immigration shapes daily life. While his role as Student Government president doesn’t give him authority over district policy, it positions him as a voice for peers facing challenges of ethnic identity under the Trump administration.

“People individually make school a better place,” Ibrahim said. “Being able to communicate not only makes things more comfortable to talk about, but [also] helps people understand the severity.”

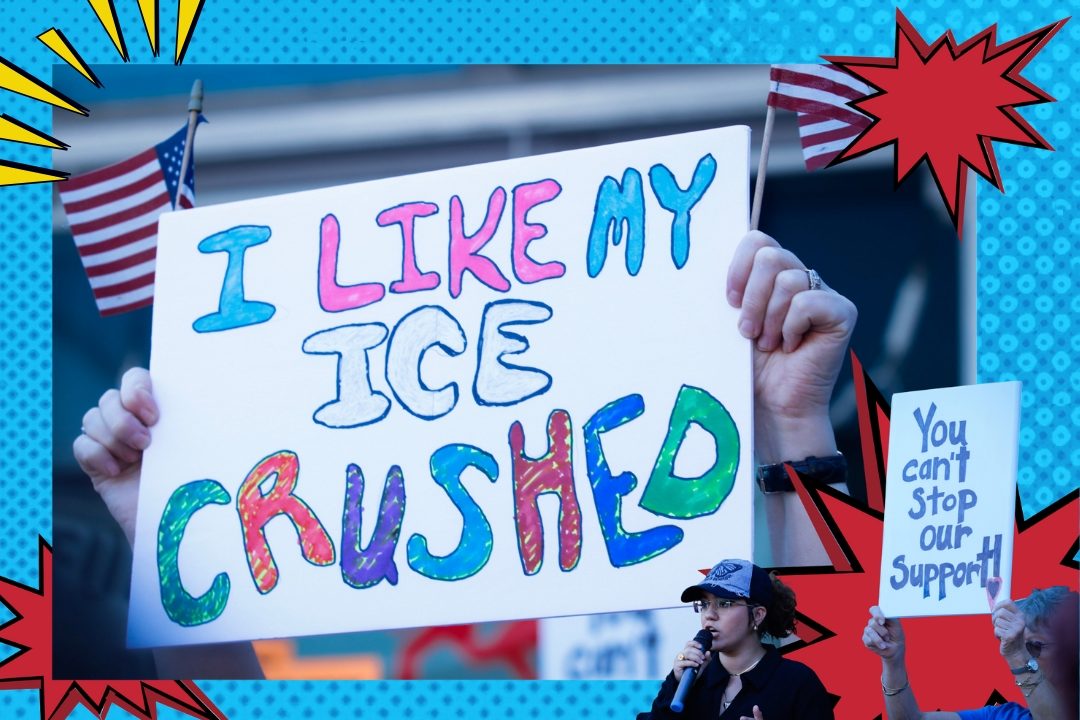

Students and teachers at West grapple with these realities inside the classroom, but the effects are also visible in the broader Iowa City community. On Sept. 26, over 350 Iowa City residents protested at the Ped Mall Fountain Stage after undercover ICE agents arrested Jorge Elieser González Ochoa, a Bread Garden employee. Immigrant-led organizations such as Escucha Mi Voz shared videos of González’s arrest, reaching sizable social media audiences. At the protest, community members — such as Katy Brown of The Kitty Corner Social Club — expressed dissatisfaction over ICE’s prominence in the area, especially over videos of González’s arrest.

“I was moved as a human being,” Brown said.“When I look at someone, I see them as a force of love and goodness in our community. I think that oftentimes, we think of people as disposable to make us feel better about the situation. [González] was a human being, a dad, a partner, a son. Somebody is always something to someone.”

Iowa City’s political unease soon connected with a nationwide headline that startled educators. On the day of the Ped Mall protest, Sept. 26, federal agents arrested Ian Andre Roberts, the superintendent of Des Moines Public Schools, citing alleged concerns about his immigration status and an outstanding firearm charge. Roberts, originally from Guyana, had led the state’s largest school district since 2023. Days after his arrest, the board voted to place him on leave. Despite his administrative leave, hundreds of Des Moines Public Schools students marched out of their schools in support of Roberts and in ridicule of ICE’s procedures.

While federal law does give ICE authority to detain immigrants, advocates like Deborah Dunkhase, co-founder of Open Heartland, a Johnson County nonprofit serving immigrant families, see the actions taken against González and Roberts as unlawful overreach. Dunkhase expresses the changes the organization has made since the OBBBA was passed in July.

“It’s horrific. It’s unconstitutional,” Dunkhase said. “The fact our government is allowing this to happen — that’s the most horrifying piece to me.”

As enforcement policies ripple outward from Washington D.C., organizations like Open Heartland have taken on roles that intersect with immigration enforcement, education and family life, providing after-school programs and legal navigation. Dunkhase said the nonprofit works to balance urgent needs with reassurance, ensuring that families know their rights and can access reliable information.

“If someone had told me five years ago how we treat new people who come to the U.S., I would have never believed it could be true,” Dunkhase said. “My heart is breaking for these families who have given up so much. There are so many challenges [in] leaving your culture, leaving your family, leaving everything you know, to come to a [new place] and find that the people in this new country are not welcoming [of] you.”

With ICE operating openly in Iowa City under Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the anxiety in classrooms and workplaces has shifted from rumor to reality. What began in Washington has now settled in local Iowan schools, where fear has spilled into the streets in the form of protests and public outcry.

This story was originally published on West Side Story on October 10, 2025.