From the courtside to the classroom, Thad Longmire ’28 sports a familiar smile and distinctive energy. Although he doesn’t wear a jersey on the field, Longmire — the sports manager for the football, basketball and track teams — remains an integral part of West High’s athletic program.

As a sports manager, Longmire’s responsibilities range from assisting football coaches with drills to operating drones and filming plays.

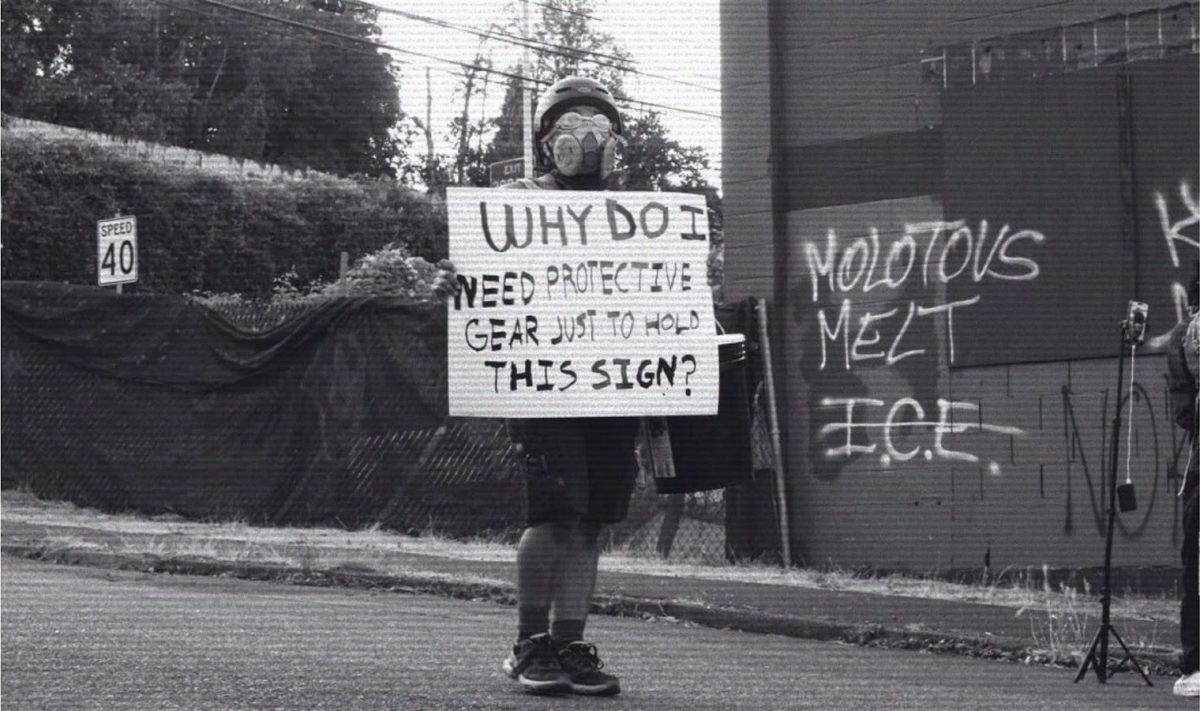

However, Longmire’s journey to discover his passion for sports was unorthodox. Born with a disability that prevents him from having arms, Longmire, unlike most kids who played on the field, discovered his vocation for sports through the screen — specifically, television and gaming.

“In sixth grade, I got an Xbox with money I earned and got my first game, Madden [NFL]. That’s how I learned most of how to play the sport, because it’s based on real-life football. Ever since, I’ve gotten really close to football,” Longmire said.

Longmire was adopted from China with his siblings, who also have disabilities. Longmire notes that his family has always upheld a gold standard, regardless of their physical limitations.

“My mom and dad encouraged me to do [football]. They’re very supportive of what [my siblings and I] do. My sister Hannah has no legs, and you see her doing track, cross country [and] winning state [competitions],” Longmire said. “You can tell she pushed [herself] and worked hard — [even] with her disability, she’s still really successful. I looked up to that because if she could do it, then I could do the same.”

However, Longmire being a sports manager wasn’t always the plan. In seventh grade, he suited up on the football field as a tight end. His former football coach and middle school science teacher, Timothy Van Dee, recalls that Longmire had a natural instinct for the game.

“The first day of football, Thad was kicking snaps to the quarterback, pretending to be the center. The guy’s feet are better than my hands — snapped it right to the quarterback,” Van Dee said.

Longmire and Van Dee first met when Longmire joined his seventh-grade science class, where Van Dee recalls he explored his interests in science as a student, as well as his passion for gaming.

“I remember Thad was playing [Fortnite] on his Chromebook. I walked over and told him ‘Alright buddy, we can’t be [gaming] at school,’ but the five people left in the classroom [started] to crowd around him, waiting for the Battle Royale win,” Van Dee said. “I don’t think I’ve ever had a louder cheer in my class than when Thad won that game. I knew right away that we would build that connection.”

After playing for the football team for a year, a serious back surgery targeting Longmire’s scoliosis cut his time as a player short.

“I had scoliosis with my spine because I use my legs [for tasks],” Longmire said. “Over time, my back started curving, so I had to get surgery [during seventh grade], because if [my spine] got too bad, the bone could mess up. Surgery made my life better, because [my back] got sore over time.”

Post-surgery, Van Dee encouraged Longmire to channel his love for football into sports management. As manager, Longmire’s spirit, whether on the field or on the sidelines, was unparalleled.

“Thad always has [charisma] and people around him,” Van Dee said. “You’re never really going to catch Thad by himself, because people want to be around him. He always has humor, cracking a joke here and there — a huge social butterfly.”

Longmire also maintains traditions to uphold team spirit. For example, he — alongside his childhood friend and teammate, Ryan Tracy ’28 — would celebrate at the 50-yard line after every win.

“After every victory since eighth grade, Thad and I meet at the 50-yard line so he can jump up and have me lift him into the air,” Tracy said. “Even though this may be corny to others, our tradition has become a staple of our friendship and the football season. Every game, when the clock is winding down and we are about to win, it has become a habit to immediately think about [our] victory celebration. Neither of us have to communicate it, because we both know that we will see each other at the 50-yard line.”

Longmire’s team spirit goes beyond celebrating victories — he’s also there to lift his teammates during their toughest moments. Throughout the season, Longmire stays cognizant of the fact that emotions run high among athletes; he recalls empathizing with injured players on the sidelines and keeping them company.

“We had a couple of injuries for football this year, and I’d just sit with them on a bench, because they tore their ACL and couldn’t walk,” Longmire said. “If [they had] a bad day, I would just hang out with them during practice and talk to them.”

Tracy echoes this, stating that Longmire would provide teammates with perspective to stay grounded and see the bigger picture.

“Every time a player is hurt on our team, Thad is the first to cheer them up and make sure they’re OK,” Tracy said. “In previous years, when [players] were down about how they performed in a game, Thad was the one to assure them that one game doesn’t define someone.”

Van Dee believes that Longmire’s ability to relate with teammates, paired with his resilience surrounding his disability, makes him an asset to the team.

“We’re talking about a kid that loves a game he can’t play — that’s gotta be a really hard thing to do, so his resilience is one of his most impressive [traits],” Van Dee said. “How does [Thad] know a game that well without playing it? How can he relate to a player and coach them in a way that they listen?”

While Longmire serves to carry out managerial tasks and support his teammates, Van Dee sees his future beyond this. He believes that Longmire’s executive vision and understanding of the game will make him a successful coach in the long run.

“He’s going to be a football coach. He’s probably smarter than me in football,” Van Dee said. “The way he watches and understands the game; the counters, ‘If they do this, we need to do that,’ or, ‘If we’re doing this, they should do that.’ He’s got a bright future in the game of football.”

Whether it be sports or science, Van Dee’s encouragement led Longmire to look up to him as a mentor and supportive figure. Having Longmire on the field and in the classroom, Van Dee sees him thrive in various areas.

“Thad is hilarious, and he’s wicked smart — [he] had an A all the way through science class. I had him on the football field as a manager, and he would see things that I would miss. He would say, ‘That tight end is on the outside of the [defensive] end, maybe we need to move the [defensive] end out to contain help,’” Van Dee said. “His football awareness, social awareness [and] educational prowess truly [makes Thad] a diamond in the rough.”

Outside of sports management, schoolwork and hobbies, Longmire’s work ethic shines through his job. Longmire currently works as a cashier at the Colony Acres Family Farm in North Liberty. Although he believes sports had the greatest impact on his work ethic, his job also played a role.

“Sports [made] me want to work harder, because in the future, I want to be a football coach at a college. That’s why I’m a manager; learning from these coaches makes me want to work harder,” Longmire said. “[My job also] definitely boosts my work ethic, because it helps me get on task.”

Tracy believes that Longmire’s hard work, intense love for football and resilience compound to encourage players on the team.

“Thad should be an inspiration to everyone,” Tracy said. “Not only [is he] inspiring [players] with what he does to help us, [but it’s also] incredible that he helps us and is a great person to be around.”

Despite Longmire’s tribulations with his disability, he believes everyone — irrespective of their physical limitations — should give their all.

“You’re here for a reason. There’s a reason why you have a disability; use it to your advantage,” Longmire said. “Some people with disabilities think they can’t do much, so they just hide themselves and don’t try. You’ve just got to try.”

This story was originally published on West Side Story on October 10, 2025.