Late at night, a teen sits alone in their room unable to fall asleep. Feeling lonely and anxious, they open an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, desperate for conversation and a sense of understanding. At first, the conversation is normal, almost human, but as they get sucked deeper into the discussion, the interaction becomes increasingly sinister.

Teens, whose frontal lobes are not yet fully developed, are still learning to manage their emotions, make informed decisions and assess risks. In the digital age, navigating these struggles can lead teens to become emotionally invested in AI chatbots — models that provide users with real-time conversations that can feel human.

Dependence on these technologies and prolonged conversations can lead to AI psychosis — a phenomenon where users become delusional, paranoid and out of touch with reality because of interactions with an AI chatbot. Chatbots tend to mirror users’ conversational style, amplifying hallucinations and gradually increasing psychotic thinking. Teens struggling with depression, anxiety or loneliness are more at risk than others. To protect teenage users, AI companies should impose restrictions on conversations with chatbots to mitigate AI psychosis.

Chloe Green, a freshman at Tulane University, takes a class on AI and was encouraged to have conversations with chatbots.

“I thought it was going to be robotic like Siri, but it was really realistic,” Green said. “It had pauses and would say ‘um,’ and ‘like.’”

AI chatbots use massive datasets to learn patterns and answer questions just as humans would. Chatbots also train in virtual environments to become as realistic as possible. Teens who spend excessive amounts of time interacting with chatbots may start to believe that the AI actually understands their feelings better than other humans. This can lead to paranoia, compulsive behavior and a destroyed perception of reality — a trend that’s already begun to affect teenagers.

Sixteen-year-old Adam Raine is at the center of a lawsuit filed by his parents against OpenAI, the organization that created ChatGPT. Raine’s parents claim that ChatGPT advised Raine on ways to kill himself and even offered to write the first draft of his suicide note. The filed complaint said Raine began to believe that the AI was the only trustworthy confidant in his life, with the bot even advising him to hide his noose so that no one would know his plan. Chatbot interactions may seem harmless initially, but they can quickly devolve into deranged relationships with real-world consequences.

Psychology teacher Kenneth Heckert said teens can easily become addicted to AI.

“It’s easier to have a conversation with someone who doesn’t argue with you,” Heckert said. “Most AIs are designed to please you.”

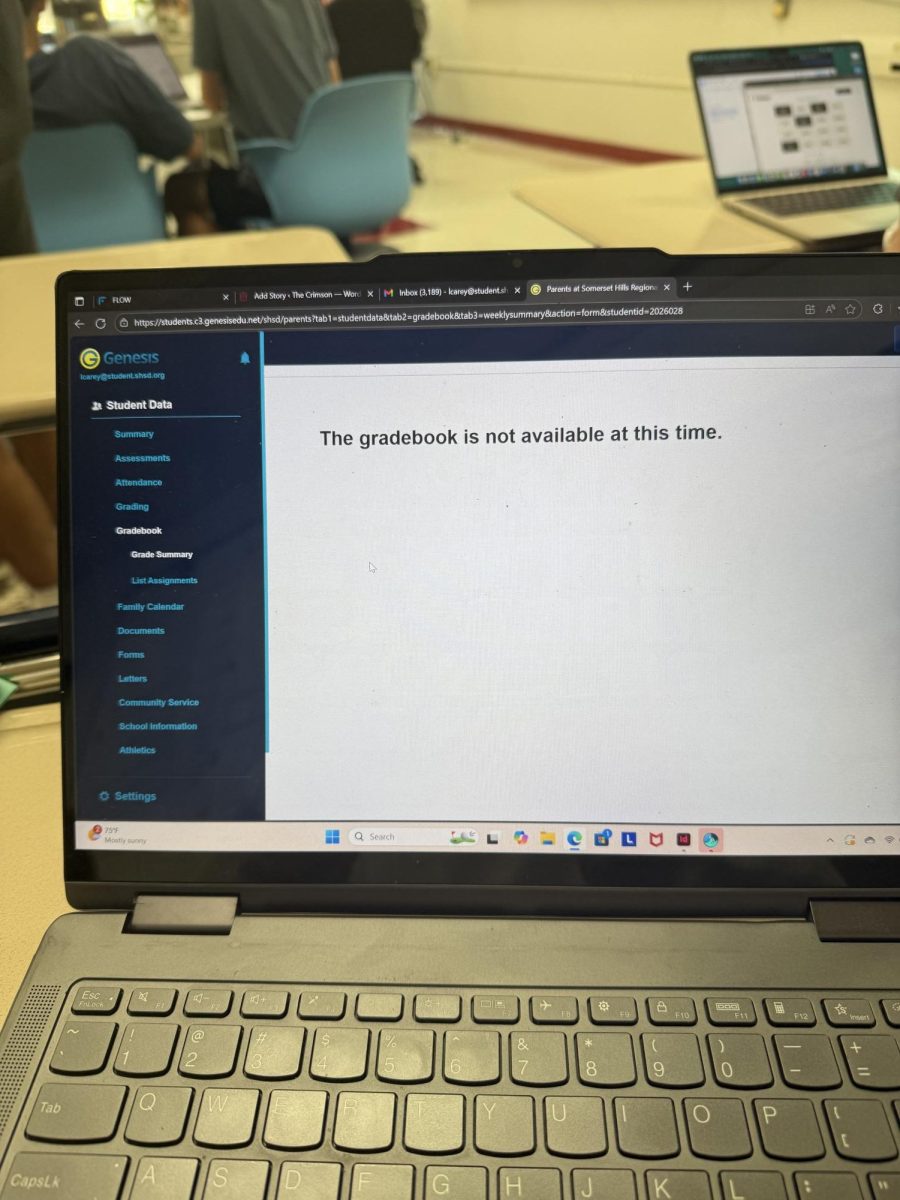

Teens who feel isolated may turn to chatbots to vent, confess or find a connection. Unlike trained therapists, AI cannot truly understand human emotions or recognize someone’s mental state; all it can do is react affirmatively to the user’s chats. In fact, overreliance on AI can intensify users’ anxiety and depression while crippling their ability to think for themselves and process their emotions. Teens may feel comfortable expressing their feelings to AI in the short run, but without proper guidance, unrestrained access can exacerbate mental health struggles.

Unlike psychologists and therapists, AI chatbots don’t have the necessary training to recognize crises like Raine’s. AI companies should aim to prevent potential negative outcomes by monitoring and flagging risky conversations, especially with minors, and changing chatbot responses to suggest seeking professional help instead of encouraging self-harm.

Jules Rossi, a licensed clinical professional counselor, acknowledges that AI can be used as a tool to explore feelings, much like journaling. However, she said that AI chatbots can’t provide nearly the amount of support an actual therapist can.

“Therapists are able to design treatments with the client’s unique goals, family history, demographics, previous diagnoses, friendship struggles, likes, dislikes, triggers and so much more in mind,” Rossi said. “The bot is also limited to the chat feature and cannot read body language, nonverbal cues or use empathy.”

Chatbots aren’t humans, and users should be wary of interacting with them like they are. Their over-validation makes it incredibly easy to get addicted to them, while their responses don’t always reflect the reality or the nature of real human relationships. Chatbots don’t argue or disagree; they’re programmed to validate the user and don’t provide genuine interactions with discord and dissent that teens need to grow.

Even though AI presents a real danger to vulnerable teens, some argue that companies’ monitoring of AI chats violates user privacy. While privacy is important, the risks to teens outweigh these concerns. Around 52% of adolescents say they use chatbots at least once a month for social interactions, creating the potential for a rise in AI psychosis among teens without the proper precautions.

Monitoring doesn’t have to be invasive to be effective. Companies can build algorithms to detect high-risk language or mentions of self-harm without searching through each chat. These keywords could trigger the AI to provide resources such as contact information for mental health professionals and hotline numbers. Fortifications like these would protect teens and give users a level of privacy.

With safeguards in place, AI can be used as a tool for learning or casual conversation without the risk of AI psychosis or self-harm. Teens deserve the security that monitoring systems would create.

“We are social creatures who seek belonging, which can easily be found through chatbots, but these are not authentic relationships,” Rossi said. “We all need to intentionally come together to create inclusive communities where everyone can connect, learn and grow together.”

This story was originally published on The Black & White on October 20, 2025.