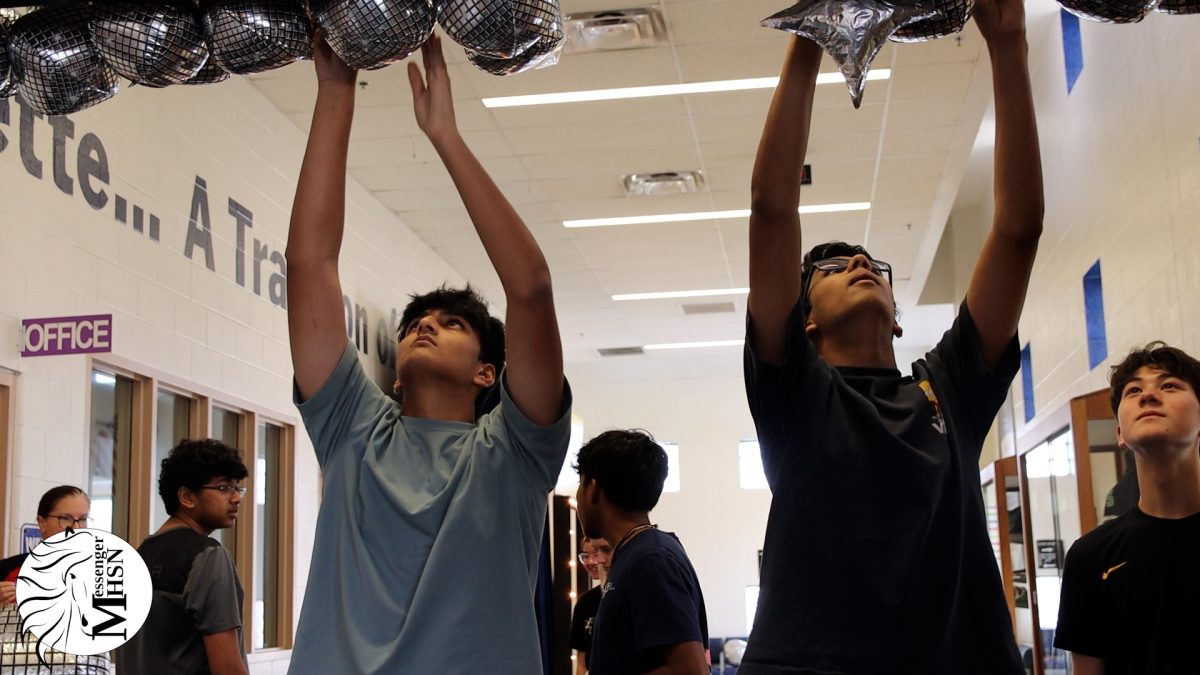

Hunched over microscopes, a group of students quietly and carefully dust and air drill away matrices from fossils that are millions of years old. While most of the volunteers are older, in college or retired, two are teenagers in high school who are turning their hobbies and interests into opportunities for a career.

Most people don’t discover their career until college, but some teens are already getting hands-on experience with paleontology through the University of Chicago’s Fossil Lab. For U-High junior Alex Dearing and senior Catherine Groves, studying fossils started out as just a curiosity but grew into a more serious interest through the Fossil Lab.

“I’m a huge dinosaur nerd. I have been for a few years, and my mom found out that there was a talk at the Fossil Lab and she was like, ‘Oh, that sounds cool,’” Catherine said.

Soon after the talk, Catherine got in touch with the Fossil Lab manager, Tyler Keillor, and set up time to volunteer.

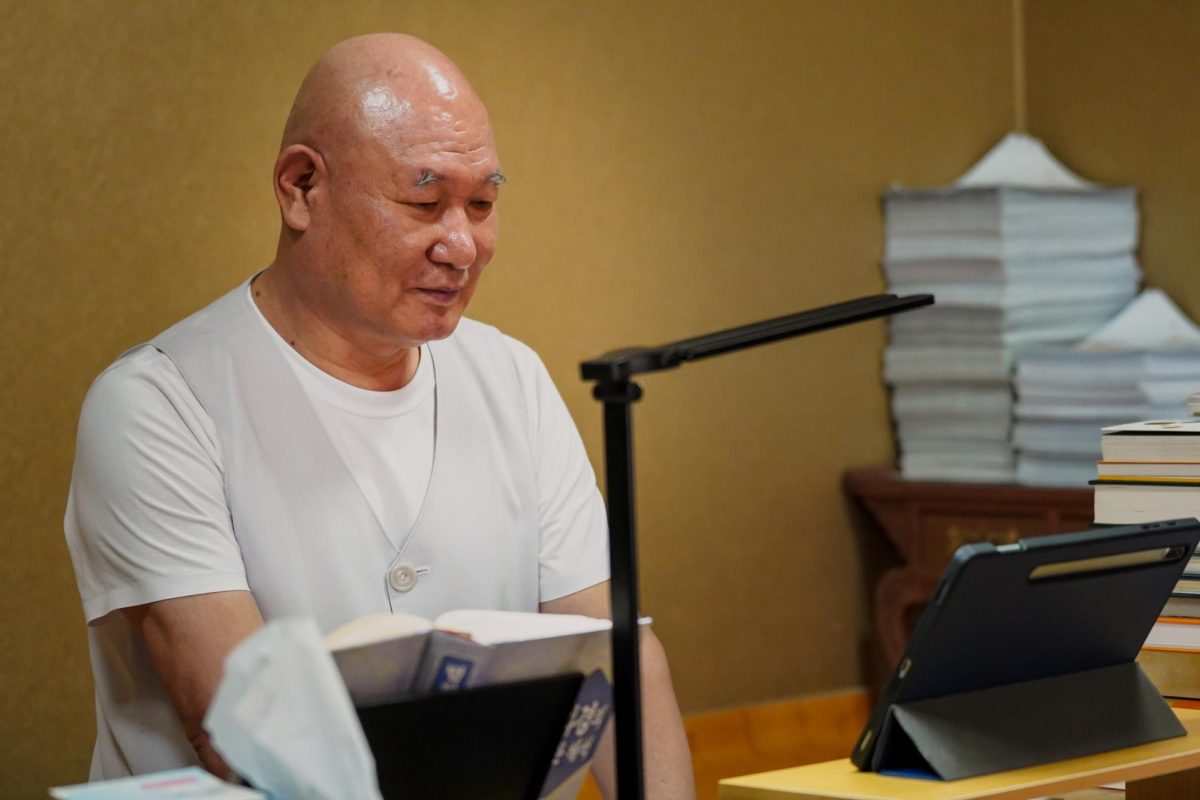

“It’s always really heartening to see new students come in who are just as enthusiastic as the little kids, who are super enthusiastic about learning about dinosaurs,” Mr. Keillor said. “Anytime you see a young person who’s that motivated and enthusiastic, it’s really special because that’s a wonderful thing.”

While one might imagine that working in a fossil lab includes reassembling bones of ancient specimens and working to identify new species, a lot of the work is on a smaller scale. When Alex first began at the lab in middle school, she spent hours at the microscope sorting through sediment, a process called microsorting.

“It is where you have a bag of sediment from a location and you scoop out in very tiny amounts, and then look under a microscope for microfossils, which could be anything from really tiny teeth to fish scales to bone fragments,” she said. “It’s important because it gets those really tiny things that you don’t see as clearly the first time around.”

Now, both Alex and Catherine regularly spend hours of their week at the Fossil Lab working on identifying, sorting and cleaning fossils. After her orientation and training Catherine went on to spend five hours every weekday at the lab but has now adjusted to only going on Wednesdays and Sundays.

“Catherine would just sit there, you know, for hours working at a microscope,” Mr. Keillor said. “Working with the tools, cleaning fossils and doing really good work, picking up the techniques really quickly and really focused and dedicated to doing a nice job.”

The long hours in the lab and the repetitive work have given Alex the confidence to pursue a career in paleontology.

“I’m more excited now, because now I know I won’t go crazy on my first day in the labs,” Alex said. “I have a tolerance for it.”

The Fossil Lab offers more than just work with specimens but also a source of connection to a field most people don’t get into until adulthood.

“Most schools do not have undergraduate paleontology classes, usually specialization you take on yourself, or rarely they’ll have someone actually teaching paleontology courses,” Alex said. “Most of the time you go to school and get a degree in biology or geology.”

In fields of science, the importance of volunteering is substantial as it allows for students to explore their interests and meet professionals in the field. Mr. Keillor said many local institutions offer programs, workshops and activities throughout the year.

Building those kinds of connections has already started to shape Alex’s path in science as she plans to use her connections at The Fossil Lab to help build her future in paleontology.

“I’m very excited because I have a lot of connections that will hopefully help me get into college,” Alex said.

While paleontology is about studying the past, for these two students, their work at the fossil lab is helping build their future.

This story was originally published on U-High Midway on October 24, 2025.