For years, “systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” infested the United States and targeted Indigenous children, stripping them of their traditions and reprimanding them if they spoke their language. A cultural genocide occurred in the country for decades, and many outside of these communities were unaware of what was happening.

Spanning from 1819 to 1970, as many as 523 schools were created across the country with the sole purpose of culturally assimilating groups of Native Americans, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians under the federal Indian boarding school system, with 408 of them receiving federal funding. The assimilation took form in many ways, but most commonly displayed itself through forbidding the use of their native languages along with their cultural and religious practices.

Within most of these schools, children were expected to adhere to strict rules and schedules. They carried out what could be seen as child labor in many states, and actively worked through different activities and lessons so that Western practices would be learned by the children rather than their own. Not only did the average day leave no room for freedom, but it was also revealed in an investigative report about these boarding schools that failure to obey often resulted in punishments such as whipping, flogging, slapping, and more, which were the norm at these boarding schools. In more extreme cases of discipline, some schools would also have the older students punish the younger ones, as it was considered an effective method.

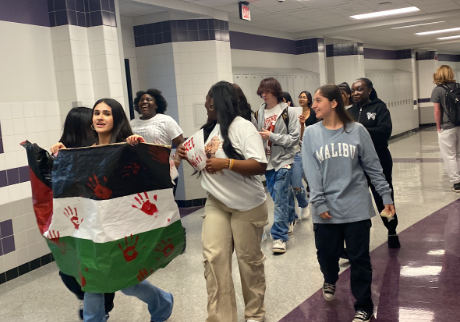

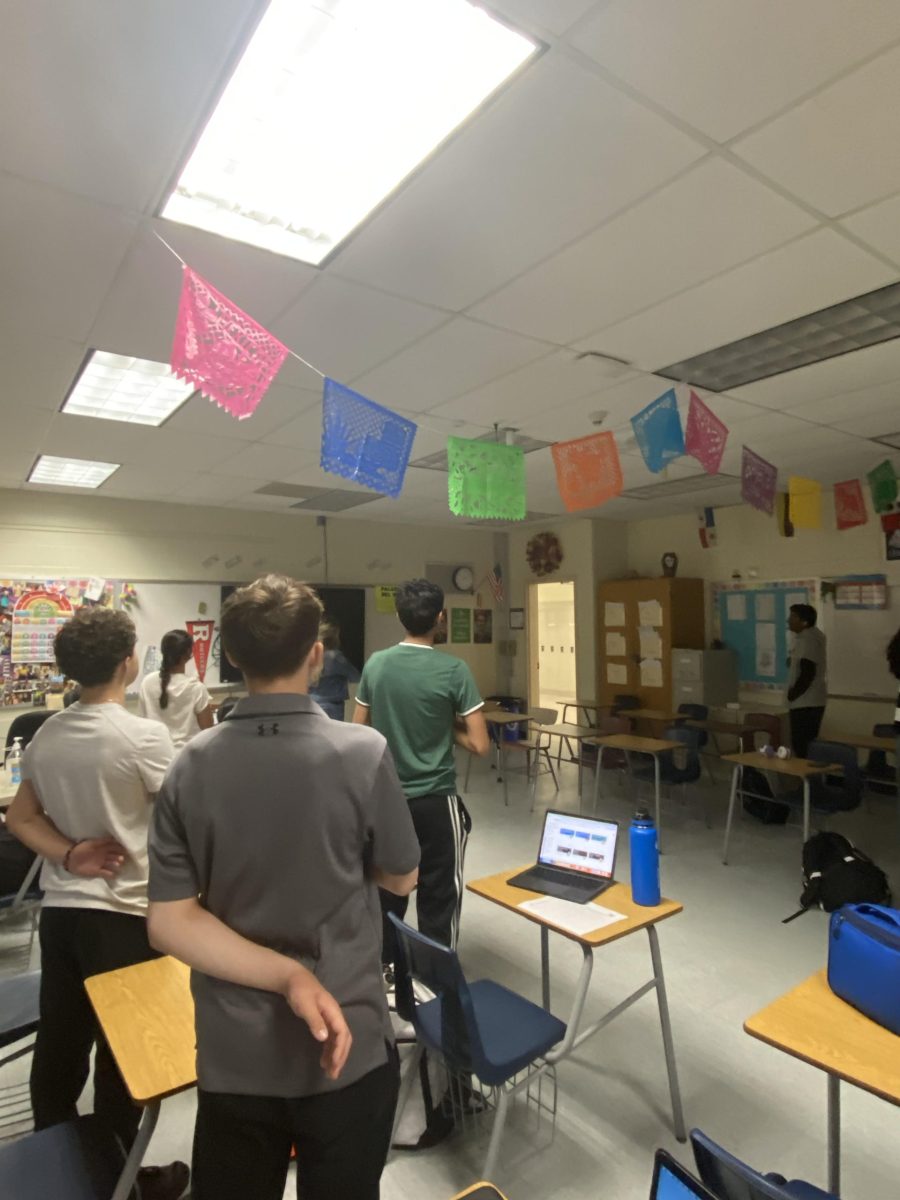

This year, to recognize the month of Native American Heritage, the Native American Student Union (NASU) helped arrange for students to watch a documentary during homerooms about the Red Cloud Indian School in the Pine Ridge Reservation of South Dakota in order for the student body to gain awareness about the history of boarding schools and how they have impacted Indigenous communities.

Mr. Mario Garza, the Director of Equity and Inclusion, who recently took this position in January, knows that the level of interest will vary among students when watching the film, but what’s important is that the students who are willing to pay attention are impacted. “Our idea is to reach whoever wants to be reached,” he said. “Just in terms of the way they view the world, maybe in terms of the way they view their fellow students.”

Amani Campbell, Officer of Inclusion within the student body, who — along with the NASU leaders — spearheaded the celebration for Native American Heritage this month, reflected on how the broad goal is to ensure that every culture feels represented, and that starts by acknowledging the issue of boarding schools since the impacts are still recent and ongoing.

“It’s important to continue to highlight it, even if some things have been settled, like compensation has been given to victim’s families,” Adeline Moreland, one of the two Native American Student Union leaders, said. For example, in January of 2021, Canada settled reparations for the indigenous communities harmed as a result of the residential schools, distributing approximately $2 billion after 215 unmarked graves of former students were found. “I think that it’s still important to bring it up every year, especially around Orange Shirt Day,” she said.

Orange Shirt Day is a time of remembrance to honor the indigenous children who were forced into boarding schools and recognize their resilience while also acknowledging the abuse and suffering they endured. This year, Orange Shirt Day fell on a Saturday, but Moreland still encouraged members of her group and community to participate. Her hope is that more students will participate in the future, no matter what day of the week.

Another way Native American Heritage has been highlighted in our community is through the land acknowledgement created by Moreland and her cousin, Annie Page, a current senior, which is used before the beginning of assemblies and other events in the school. The acknowledgement recognizes the indigenous people who lived on the land before the school existed, ranging from the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde to the Molalla, Kalapuya, and Clackamas tribes and bands.

The NASU, alongside Mr. Garza, has been working towards a goal of having a land acknowledgment plaque displayed on campus. According to Mr. Garza, “the movement from words to getting something more permanent on our campus” is important, especially in the context of a Catholic high school. “Unfortunately, at various times, the greater Catholic Church played a role in some of these issues,” Mr. Garza said.

He noted that, no matter where he is, whether it be at a conference or outside of school, there is likely to be a land acknowledgement, but the impact of something more tangible still stands. “There’s a lot of power in having that kind of memorial in a high school like ours,” he said.

The idea of showing a film coincided with this objective and the fact that having an assembly would be out of the range for the NASU, as there aren’t many people within the group that could or were willing to speak. “It’s hard to listen when it’s just educational, like you need something that’s actually fun and interesting, but you are also learning at the same time,” Campbell said, in relation to deciding what they would do to spur more engagement for students and awareness.

Within the school, he believes that teachers are efficient with implementing a range of voices in the curriculum when it applies to things like English or Social Studies. “I think a lot of the things that we’re doing are almost becoming so institutionalized here where people are just doing it, which I think is great, but it’s also one of those things you have to continue to be intentional about,” he said. “If you do something once and then forget about it, chances are the students are going to forget about it.”

Returning from COVID, creating engagement around affinity groups and heritage months was difficult, but the goal for affinity groups remains to create a space for students of all backgrounds. Moreland said that during her first two years at La Salle, the heritage months that had larger populations at the school were more likely to be celebrated. Furthermore, the NASU didn’t exist until her junior year. “It has been underrepresented in the past,” she said.

“It’s important just to make sure that we recognize the various backgrounds, cultures, [and] students that make up our community, because it can be difficult for some of these people depending on where they grew up, depending on what their middle school experience may have been like,” Mr. Garza said.

Considering the histories and issues embedded in heritage months, Mr. Garza believes that as a community, the school should work to make sure that heritage isn’t only recognized within the allotted time and to not be bound by a month alone. “We have posters all over campus about these famous Native Americans, I couldn’t tell you how many kids are taking the time to look at those and reflect on those things,” he said. “But even if a few are, I think that’s important.”

This story was originally published on The La Salle Falconer on November 29, 2023.

![With the AISD rank and GPA discrepancies, some students had significant changes to their stats. College and career counselor Camille Nix worked with students to appeal their college decisions if they got rejected from schools depending on their previous stats before getting updated. Students worked with Nix to update schools on their new stats in order to fully get their appropriate decisions. “Those who already were accepted [won’t be affected], but it could factor in if a student appeals their initial decision,” Principal Andy Baxa said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53674616658_18d367e00f_o-1200x676.jpg)

![Junior Mia Milicevic practices her forehand at tennis practice with the WJ girls tennis team. “Sometimes I don’t like [tennis] because you’re alone but most of the time, I do like it for that reason because it really is just you out there. I do experience being part of a team at WJ but in tournaments and when I’m playing outside of school, I like that rush when I win a point because I did it all by myself, Milicevic said. (Courtesy Mia Milicevic)](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/c54807e1-6ab6-4b0b-9c65-bfa256bc7587.jpg)

![The Jaguar student section sits down while the girls basketball team plays in the Great Eight game at the Denver Coliseum against Valor Christian High School Feb. 29. Many students who participated in the boys basketball student section prior to the girls basketball game left before half-time. I think it [the student section] plays a huge role because we actually had a decent crowd at a ranch game. I think that was the only time we had like a student section. And the energy was just awesome, varsity pointing and shooting guard Brooke Harding ‘25 said. I dont expect much from them [the Golden Boys] at all. But the fact that they left at the Elite Eight game when they were already there is honestly mind blowing to me.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_7517-e1716250578550-900x1200.jpeg)

![BACKGROUND IN THE BUSINESS: Dressed by junior designer Kaitlyn Gerrie, senior Chamila Muñoz took to the “Dreamland” runway this past weekend. While it was her first time participating in the McCallum fashion show, Muñoz isn’t new to the modeling world.

I modeled here and there when I was a lot younger, maybe five or six [years old] for some jewelry brands and small businesses, but not much in recent years,” Muñoz said.

Muñoz had hoped to participate in last year’s show but couldn’t due to scheduling conflicts. For her senior year, though, she couldn’t let the opportunity pass her by.

“It’s [modeling] something I haven’t done in a while so I was excited to step out of my comfort zone in a way,” Muñoz said. “I always love trying new things and being able to show off designs of my schoolmates is such an honor.”

The preparation process for the show was hectic, leaving the final reveal of Gerrie’s design until days before the show, but the moment Muñoz tried on the outfit, all the stress for both designer and model melted away.

“I didn’t get to try on my outfit until the day before, but the look on Kaitlyn’s face when she saw what she had worked so hard to make actually on a model was just so special,” Muñoz said. “I know it meant so much to her. But then she handed me a blindfold and told me I’d be walking with it on, so that was pretty wild.”

Caption by Francie Wilhelm.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53535098892_130167352f_o-1200x800.jpg)