“Rizz” was crowned as the word of the year in 2023 by Oxford University Press. Every year, Oxford University Press hosts a “word of the year” contest, and in 2023, the contest was extended to allow the general public to participate. Each person was allowed to vote for one of the eight words Oxford University Press had pre-selected, and the word with the most votes was “rizz.” The term comes from the word “charisma” and is used to indicate a high-level proficiency in flirting with someone.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, slang is defined as “language peculiar to a particular group.” Slang is often used as an indication of belonging to a group or as a way of expressing attitudes towards another group. Slang also commonly differs between people, and can be recycled and revived from previous generations.

New terms are often coined to accommodate slang for rising generations or to communicate a shared experience. For example, phrases such as “the ‘rona” and “Zoom fatigue” emerged during COVID-19, and words such as “delulu” and “cooked” were popularized over social media platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok.

According to Preply, Generation Z — people born between 1997-2012 — uses slang the most out of any other generation, and 89% of Americans learn slang from the internet and social media. However, new slang doesn’t strictly emerge from generation to generation; it often originates from African American Vernacular Language.

Defining Generational Slang

History teacher Nicholas Graham defines generational slang as the colloquial, informal language that each generation uses as its own in order to separate itself from previous generations. Graham also cited the example of cockney rhyming slang — a coded language criminals in England used to avoid law enforcement – as a model of how language has evolved to fit a group’s needs, especially when used for isolation.

“[Slang] adds a bit of spice to what you’re saying a lot of the time. If we were all to communicate formally, in the way that I’m doing now, I think that life would be a little bit dull,” Graham said. “Language is rich after all. Slang is wonderfully creative, wonderfully inventive. It can also be almost like a secret code.”

Math teacher Matthew Bartha defines generational slang as the sociological evolution of culture. Bartha said he sees slang developing anywhere, such as within groups who share commonalities. During class, Bartha often uses slang in his interactions with students.

“I feel like younger generations always [want to] look like they’re cool — they want to look separate, different or unique,” Bartha said. “So, they form their own ways of communicating based on their culture and whatever else is going on at the time.”

Champs Charter High sophomore Atticus Perry was born into Generation Z and said he feels as though he does not use slang correctly. Perry elaborated that he commonly uses terms from past generations, such as “bummer” or “swell,” but he will probably pick up new phrases with the emergence of Generation Alpha.

“[Slang] has kind of stuck with me, and probably will continue to stick with me,” Perry said. “I feel like every generation starts picking up whatever the younger generation is saying. So that’s probably going be me, but I’m going to be really bad at it. And my grandchildren will be like, ‘Oh my god, like just stop.'”

Graham, who has also taught at schools in Britain, said he noticed an increase in diversity of slang there. He said he believes more people introduce slang from their cultures in the United Kingdom, in comparison to the United States.

“I think [slang] seems to me far more commonplace in the United Kingdom than it does in the United States. The UK is diversifying all the time,” Graham said. “A lot of slang terms entering usage amongst the younger generation have come from, say Jamaica, or from Vietnam because these various countries are introducing their own slang terms. Now, our population in terms of its diversity, it looks ever so slightly different to the United States.”

Slang Inside and Outside the Classroom

Graham said even though he works with students, he is not familiar with Generation Z slang as he speaks in a semi-formal classroom setting on a day-to-day basis. He added that while he enjoys using British slang in American classrooms to see the reaction on his students’ faces, he does not feel comfortable adopting Generation Z slang into his own vocabulary.

“Older generations should not be adopting the slang of younger generations. Leave them alone. It’s not for you,” Graham said. “The reason that a generation acquires and develops its own slang is to mark itself off from [other groups], almost as an act of rebellion. So to hear older people speak, it would be really quite sad. I think I come off a bit of an idiot.”

Loyola High School sophomore Selene Earley was born into Generation Z and said she does not often use slang in her everyday life because she does not have a habit of using it. Earley added that within school, it felt amusing yet unnatural to hear teachers use slang from younger generations.

“The other day, my theology teacher — who is kind of old — described his outfit as ‘skibidi’, and everyone was trying not to laugh,” Earley said. “If you understand what [Generation Z slang] means and you use it correctly, then it should be fine.”

While conversing with friends and family outside the classroom, Perry not only adopts new slang, but notices his family using the same slang he does.

“I use slang with my friends a lot. Sometimes I use it with my parents, and then they’ll pick it up and then they won’t drop it,” Perry said. “Everyone in my family has been saying ‘sus’ since 2020. Including my grandmother, who I was talking to once and she was like, ‘Man, this is just pretty sus,’ and I felt a little part of me die inside.”

As a part of Generation Z, Archer sophomore Serenity Jones said she subconsciously uses slang during assignments, even when she does not mean to.

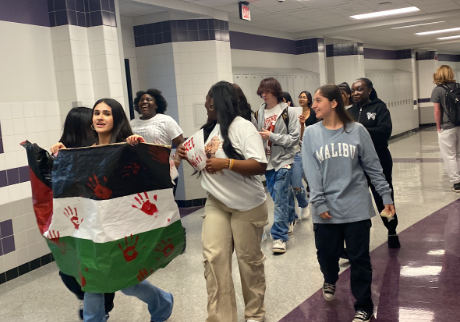

“I’ve definitely noticed it in my writing where if I’m trying to say ‘low key,’ I’ll put ‘lowk’ and I’ll be writing in history or something. When we’re drafting an English, I’ll put ‘LMFAO’ in my annotations and all that,” Jones said. “I can definitely notice [slang] in my life, but since I code-switch. It’s easier for me to differentiate when to not use it and when to use it. Especially in my writing, it doesn’t really change that much in my life because I know that I’ve grown up knowing the difference already.”

Code switching is the practice of switching between languages during conversation. Jones said she code-switches after she comes home from school, which has affected her perception of the English language.

“At Archer, I have a very different voice when I’m talking to certain teachers and faculty members, whereas at home, I have a bit more of a different cadence when I talk to my family or friends,” Jones said. “When I’m here, I try to be more lively and more professional. Whereas when I’m home, I’m trying to be casual and live my life in peace.”

Problems With Generation Z Slang

Many people born into Generation Z use terms such as “rizz,” “cap” and “slay,” which are derived from African American Vernacular English. Celebrities and the usage of social media has popularized such terms. Without a clear origin, terms such as “rizz” or “cap” are seen as created by Generation Z instead.

Jones said she grew up using AAVE around her family and considers Generation Z slang to come from AAVE instead.

“It’s kind of weird when people at Archer trying to use it because it doesn’t sound right. I think here, people go based off of what they hear off TikTok,” Jones said. “But it’s words that I’ve already been using. People start using it and then they’ll give up on it. Whereas, I’ll keep saying it because it’s something that I grew up with and never stopped using.”

According to an Oracle survey sent to all 267 upper school students, only 37 responded. An anonymous student reported they hate the term “Gen Z slang” when asked to give their additional thoughts on Generation Z slang.

“TikTok and other social media popularized these terms and have turned them into universal vernacular when it’s supposed to be African American vernacular,” one student wrote in their survey response.”The reason why it’s so frustrating is because it’s used incorrectly and way too often and no one knows where these words come from. People think some random teenagers just came up with it when really Black people and queer people have been using these words for decades. It’s really, really annoying.”

In addition to noticing how slang is often popularized and marketed to students through TikToks, Bartha said he has noticed growth in how quickly Archer students adopt slang from social media.

“From what I understand, Archer girls are late to a lot of things — or maybe they’re late in telling me — but I think it allows things to go viral more so I think [slang] spreads faster,” Bartha said. “It also dies out quicker: people’s attention [spans] go down, and then they’re on to the next video that causes kids to say things don’t make any sense.”

Perry said he sees new slang emerge every few months, but feels many terms never fully lose relevance.

“You get little packages of slang every few months. ‘Slay’ is pretty popular and starting to slowly [settle],” Perry said. “Some [terms] can last up to a year but overall, I don’t think slang really ever fully lessens if you’re talking to somebody and they start saying a common catchphrase or common little bit of slang. Slang comes in waves, and I don’t think it’ll ever fully dissipate.”

Graham said while he does not think slang can withstand the test of time as generations die out, it can be preserved through literature.

“If you come across a term from a book written in the early 20th century or something, you have to appreciate that was a term that was popularized at that time,” Graham said. “But language is always evolving. Language changes. keeps up with the times, and it’s richer for that as well.”

This story was originally published on The Oracle on May 27, 2024.

![With the AISD rank and GPA discrepancies, some students had significant changes to their stats. College and career counselor Camille Nix worked with students to appeal their college decisions if they got rejected from schools depending on their previous stats before getting updated. Students worked with Nix to update schools on their new stats in order to fully get their appropriate decisions. “Those who already were accepted [won’t be affected], but it could factor in if a student appeals their initial decision,” Principal Andy Baxa said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53674616658_18d367e00f_o-1200x676.jpg)

![Junior Mia Milicevic practices her forehand at tennis practice with the WJ girls tennis team. “Sometimes I don’t like [tennis] because you’re alone but most of the time, I do like it for that reason because it really is just you out there. I do experience being part of a team at WJ but in tournaments and when I’m playing outside of school, I like that rush when I win a point because I did it all by myself, Milicevic said. (Courtesy Mia Milicevic)](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/c54807e1-6ab6-4b0b-9c65-bfa256bc7587.jpg)

![The Jaguar student section sits down while the girls basketball team plays in the Great Eight game at the Denver Coliseum against Valor Christian High School Feb. 29. Many students who participated in the boys basketball student section prior to the girls basketball game left before half-time. I think it [the student section] plays a huge role because we actually had a decent crowd at a ranch game. I think that was the only time we had like a student section. And the energy was just awesome, varsity pointing and shooting guard Brooke Harding ‘25 said. I dont expect much from them [the Golden Boys] at all. But the fact that they left at the Elite Eight game when they were already there is honestly mind blowing to me.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_7517-e1716250578550-900x1200.jpeg)

![BACKGROUND IN THE BUSINESS: Dressed by junior designer Kaitlyn Gerrie, senior Chamila Muñoz took to the “Dreamland” runway this past weekend. While it was her first time participating in the McCallum fashion show, Muñoz isn’t new to the modeling world.

I modeled here and there when I was a lot younger, maybe five or six [years old] for some jewelry brands and small businesses, but not much in recent years,” Muñoz said.

Muñoz had hoped to participate in last year’s show but couldn’t due to scheduling conflicts. For her senior year, though, she couldn’t let the opportunity pass her by.

“It’s [modeling] something I haven’t done in a while so I was excited to step out of my comfort zone in a way,” Muñoz said. “I always love trying new things and being able to show off designs of my schoolmates is such an honor.”

The preparation process for the show was hectic, leaving the final reveal of Gerrie’s design until days before the show, but the moment Muñoz tried on the outfit, all the stress for both designer and model melted away.

“I didn’t get to try on my outfit until the day before, but the look on Kaitlyn’s face when she saw what she had worked so hard to make actually on a model was just so special,” Muñoz said. “I know it meant so much to her. But then she handed me a blindfold and told me I’d be walking with it on, so that was pretty wild.”

Caption by Francie Wilhelm.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53535098892_130167352f_o-1200x800.jpg)