Over 100 students were held back from joining their senior class at the beginning of this year. The student body’s failing classes continue to cause issues for the administrative team.

Despite the number of students failing, head principal Andrew Neely stays optimistic about the student body’s ability to pass their courses.

“I know, and I believe that my teaching staff will work with any student, as long as the student is willing to work,” Neely said. “Very rarely is there a time where I think a student has a good reason as to why someone would not earn credit for a course.”

Although Neely has a desire to have all students pass, people continue to fail courses. The administrative team worked on fixing this issue because they want to see students graduating and taking the next step in their lives. A solution appeared when assistant principal Kerri Harrington attended a nationally required class for her principalship. During the class, Harrington and other principals learned about Dr. Henry A. Wise Jr. High School. The school offered a program for credit recovery that students would sign up for in order to earn back lost credits.

“When I returned from that course I brought it up during one of our Tuesday meetings. [It was] something interesting that came out of that course, and the more we talked about it and saw the amount of kids who were retained, we thought this might be a nice idea to try to help some of those kids get pushed forward a little bit,” Harrington said, “So we took that idea and ran with it. We tried to make it work for us and help some kids who have fallen behind a little bit.”

After planning out the program, students who were falling behind received the offer for two types of credit recovery. The first option is focused credit recovery where students are scheduled into one class for most of the day. The students using this pathway have lost almost a year’s worth of credits. They complete a full year’s worth of core courses over the span of one semester. This is achieved through supervised ACA courses with teachers who are present the full day. After the semester is up, these students will participate in their current year courses.

“It really takes dedication to buckle down on your academics, especially for kids who are behind. That’s not easy to do,” Harrington said.

Students are also given the chance to participate in the regular credit recovery program. Students who are offered this option often only have one or two credits missing. They are put into a study hall where they work on receiving their missing credits through ACA. A teacher supervises the study hall, and the class continues throughout the whole year.

Before getting into either program, students must qualify. Counselors and principals work together to determine which students seem like a good fit for the program.

“If a student missed a ton of school days, they’re probably not who we feel are going to show up every day. If a student had a lot of discipline issues, where it looks like they’re going to have some trouble just buckling down, then that might not have been a student who might qualify to be in the program,” Harrington said.

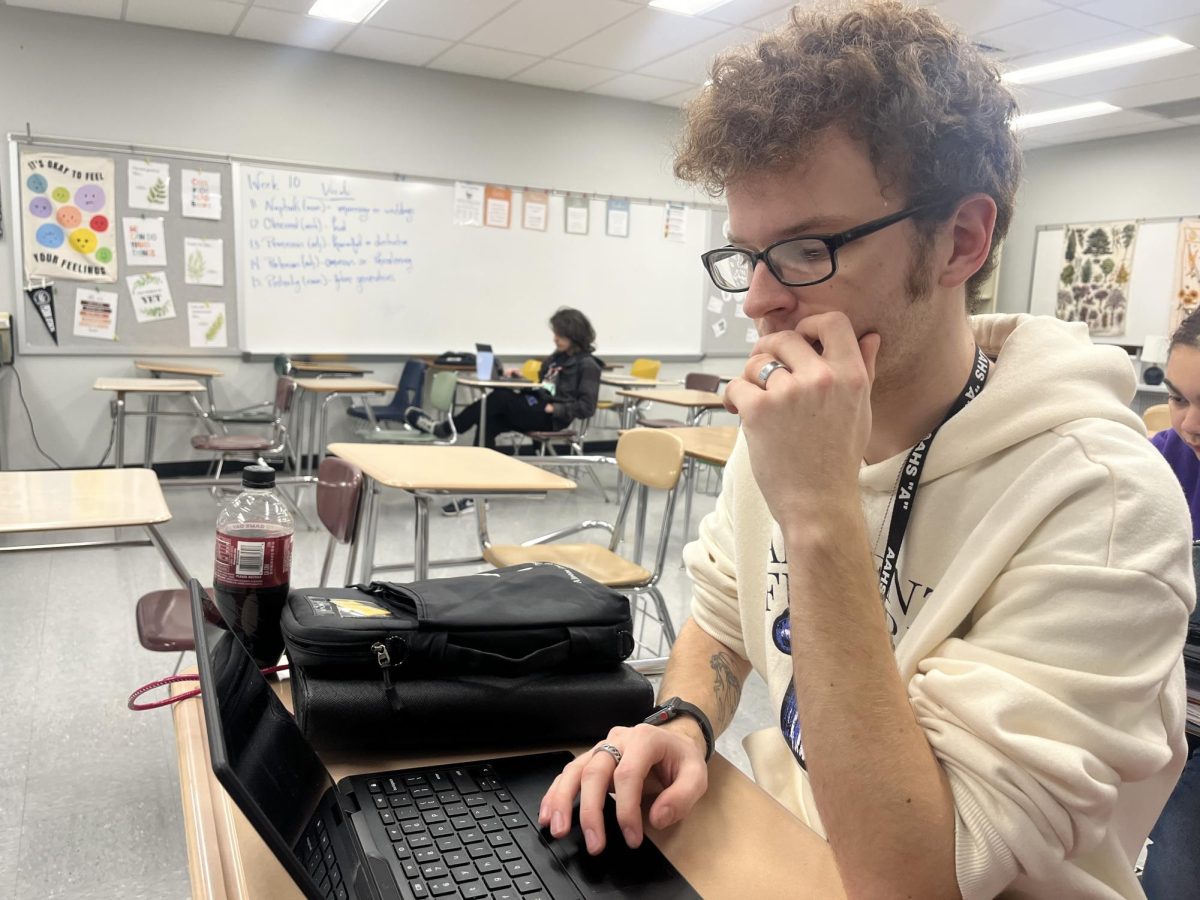

Senior Nickolas Stevenson failed his first two years as a freshman. He took his classes through the cyber program for both of his first two years.

“Once COVID-19 hit, that’s when everything went downhill. The lockdown put me in sort of a state of depression. And because of that, my academics dropped. So I had to get held back,” Stevenson said. “My second year of ninth grade wasn’t really any better. The lockdown was still in effect, and family issues were occurring. So I just put my education on the side.”

After failing his second freshman year, Stevenson was only able to get two credits through summer school. He was ready to give up on his education.

“I wanted to get done with it. And I was in a position where I didn’t think there was a way to climb out of it. So I just didn’t do anything,” Stevenson said. “I didn’t really care about my education whatsoever. And I was already planning on dropping out and getting my GED.”

However, Stevenson’s plans changed when his counselor made a plan for him to go back to school in person. Stevenson felt inspired by the plan, and his mindset changed.

“I wanted to prove to myself that I could graduate. Cyber school wasn’t the right option for me, and it took me a while to realize that. I was able to knock some sense into myself and go back to school because I knew how important it was,” Stevenson said.

His first year back didn’t go as smoothly as planned, but he was offered the opportunity to take the credit recovery program the next year. By the time he finished his third year at the high school, Stevenson turned his two credits into 12 with the help of summer school.

When he entered his fourth year at the high school, Stevenson was considered a junior. He had the credit recovery program incorporated into his schedule, and he worked with the program to get him to 23 credits by the end of the year. Stevenson’s first period is a study hall with Kathryn Salada, where he works on making up his English 10 credit.

Besides the credit recovery program, Stevenson also utilizes other programs to help him receive more credits. He plans on taking biology in summer school, and he currently takes work experience through the cyber program to receive another two credits. By the end of the year, Stevenson plans to accumulate 23 total credits, meaning he will graduate at risk.

Graduating at risk occurs when a counselor approaches Neely to discuss a specific student’s situation. They ask him to consider allowing a student to graduate depending on previous events that may have prevented them from accumulating all necessary credits.

Once the first semester ended, administrators saw positive progress. Due to the credit recovery program and other students passing their first semester courses, the student body saw people advancing to the next grade.

“I’m happy to say that after the first semester concluded, we promoted about 60 students out of that roughly 100 back up to senior status because they’re doing what they need to do,” Neely said.

While the regular credit recovery program has had positive outcomes, the focused credit recovery has had less success.

“The focused credit recovery is much more difficult to maintain as far as record keeping and grade reporting goes. And we’re finding that not that many kids qualify for it, so I don’t know if we’ll continue on with that next year or not,” Harrington said. “But we have had a lot of success with kids in the regular credit recovery, where they’re just working on one course.”

Even with the success it has had, the credit recovery program has shown it doesn’t work for every student.

“When they [students in the program] start to do it, they realize that it’s a ton of work…so that can become very overwhelming,” Neely said. “So I don’t know if the system is for every student. It’s for a certain group that is willing and able to accelerate that way. So it’s not a one size fits all solution.”

Although the program does help certain students, it is not meant to be a solution for all students. Neely warns students that they should keep up with their classes before they decide to depend on the program.

“[Students] work the hardest that you can to the best of your ability in your classes. And if you’re falling behind in a class, you need to talk with the teacher first and foremost. Then if it’s still not working out, school counselors are the next line of defense, and so are grade level principals,” Neely said, “There’s a lot of people here that are here to help you stop from getting that point. No one wants to be in that position.”

This story was originally published on Mountain Echo on February 21, 2024.

![With the AISD rank and GPA discrepancies, some students had significant changes to their stats. College and career counselor Camille Nix worked with students to appeal their college decisions if they got rejected from schools depending on their previous stats before getting updated. Students worked with Nix to update schools on their new stats in order to fully get their appropriate decisions. “Those who already were accepted [won’t be affected], but it could factor in if a student appeals their initial decision,” Principal Andy Baxa said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53674616658_18d367e00f_o-1200x676.jpg)

![Junior Mia Milicevic practices her forehand at tennis practice with the WJ girls tennis team. “Sometimes I don’t like [tennis] because you’re alone but most of the time, I do like it for that reason because it really is just you out there. I do experience being part of a team at WJ but in tournaments and when I’m playing outside of school, I like that rush when I win a point because I did it all by myself, Milicevic said. (Courtesy Mia Milicevic)](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/c54807e1-6ab6-4b0b-9c65-bfa256bc7587.jpg)

![The Jaguar student section sits down while the girls basketball team plays in the Great Eight game at the Denver Coliseum against Valor Christian High School Feb. 29. Many students who participated in the boys basketball student section prior to the girls basketball game left before half-time. I think it [the student section] plays a huge role because we actually had a decent crowd at a ranch game. I think that was the only time we had like a student section. And the energy was just awesome, varsity pointing and shooting guard Brooke Harding ‘25 said. I dont expect much from them [the Golden Boys] at all. But the fact that they left at the Elite Eight game when they were already there is honestly mind blowing to me.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_7517-e1716250578550-900x1200.jpeg)

![BACKGROUND IN THE BUSINESS: Dressed by junior designer Kaitlyn Gerrie, senior Chamila Muñoz took to the “Dreamland” runway this past weekend. While it was her first time participating in the McCallum fashion show, Muñoz isn’t new to the modeling world.

I modeled here and there when I was a lot younger, maybe five or six [years old] for some jewelry brands and small businesses, but not much in recent years,” Muñoz said.

Muñoz had hoped to participate in last year’s show but couldn’t due to scheduling conflicts. For her senior year, though, she couldn’t let the opportunity pass her by.

“It’s [modeling] something I haven’t done in a while so I was excited to step out of my comfort zone in a way,” Muñoz said. “I always love trying new things and being able to show off designs of my schoolmates is such an honor.”

The preparation process for the show was hectic, leaving the final reveal of Gerrie’s design until days before the show, but the moment Muñoz tried on the outfit, all the stress for both designer and model melted away.

“I didn’t get to try on my outfit until the day before, but the look on Kaitlyn’s face when she saw what she had worked so hard to make actually on a model was just so special,” Muñoz said. “I know it meant so much to her. But then she handed me a blindfold and told me I’d be walking with it on, so that was pretty wild.”

Caption by Francie Wilhelm.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53535098892_130167352f_o-1200x800.jpg)