Just behind Kentner Stadium is a corner of campus that few students venture to regularly. Each weekday, environmental program students and anthropology majors spill out of their department’s respective homes, isolated from Wake Forest University’s other academic buildings. Athletes trek to the Miller Center. Pickleball players head to the courts. Those who find themselves in this unusual corner of campus are greeted by a strange sight if they look up.

There, two large satellite dishes and a silver tower loom behind a pale yellow farmhouse. The tiny shuttered house looks a bit out of place on a campus renowned for its Virginian brick. This building isn’t a small-town dentist’s office, though. Since 1991, it has been the home of Winston-Salem’s local National Public Radio (NPR) affiliate station: WFDD.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, most employees only come in three days a week. On the day I visit, only a few employees, including radio engineer George Newman, reporter April Laissle and local “Morning Edition” host Neal Charnoff are there as Molly Davis, assistant station manager and WFDD employee since 2005, shows me around.

The rest of the farmhouse is home to three recording studios, an engineering room filled with ceiling-high radio transmitting technology and storage closets.

Each studio is used differently depending on size and availability, although all three can broadcast directly over the air. WFDD’s broadcast schedule currently consists of a mix of local and national NPR content throughout the waking hours and classical music from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., at which point “BBC World Service” begins the day.

The farmhouse is the office of some, but not all, of WFDD’s approximately 20 employees. Others work in offices on Reynolds Boulevard inside of the University Corporate Center, a large glass-paned building about a two-mile drive down busy University Parkway from Wake Forest’s campus.

At the moment, there are prospective plans to move the station off-campus entirely within the next few years, a move that would further distance the station from its founding body– Wake Forest students.

“Most students don’t know we’re here,” Davis said.

The lack of student awareness about WFDD is perhaps unsurprising on the surface. Not many Wake Forest students are prone to listening to NPR in their free time — at least not over the radio waves. Yet, others see this disconnect as the result of years of student separation from a station whose name, ironically, is short for Wake Forest Demon Deacons.

***

In 1946, Wake Forest students Henry Randall and Al Parris illegally aired the first-ever broadcast of what, at the time, was known as W-A-K-E radio from the old campus of Wake Forest College in Wake Forest, NC. Two years later, after brothers David Herring and Ralph Herring Jr. built a transmitter under the direction of WRAL Raleigh’s radio engineer, the station received a license from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and changed its name to WFDD. The station aired its inaugural broadcast from Wake Forest, N.C. featuring then-college president Dr. Thurman D. Kitchin.

A year after the station’s officially sanctioned establishment, Jack Thomas arrived on the Wake Forest College campus and immediately became involved with the station. Today at 95 years old, Thomas lives in a Winston-Salem retirement community, still regaling the memories from the station’s early days. As Thomas recalls, its university-sanctioned founding grew out of the popularity of Randall and Parris’ bootleg station, which could be heard from the girls’ dormitory nearby.

By 1949, WFDD was three years removed from Parris and Randall’s first escapade into campus radio, and one year into a legally licensed, university-sponsored station. The infrastructure for broadcasting had significantly improved.

“By the time I got there, they had wired the campus,” Thomas explained. “There was a telephone wire going through the trees and a microphone in the church.”

This system of electrical wires allowed WFDD to broadcast both from its control room in an old sorority house just off campus, as well as from the chapel.

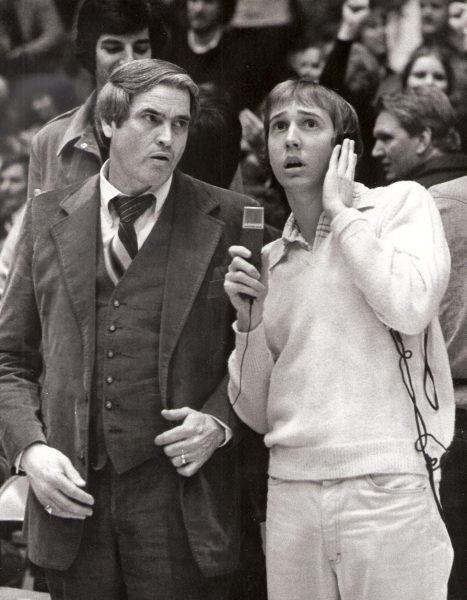

Thomas was part of a group of 10 to 15 students who broadcast scripted, pre-recorded and original programs including classical music, educational programming and sports. His interests lay mainly in sports and educational content at that time. He frequently accompanied sports commentators to away games at various schools around the state. There, he manned the equipment and read ads between breaks.

Despite his interest in radio, Thomas was not a music fanatic at the time. He was quite the opposite.

“I was pretty religious then, and I didn’t like some of the songs, so I scratched ‘em,” he admitted regarding some of the records the studio received.

Despite Thomas’ misgivings about the station’s musical content, it flourished in time. It was during this time that one of WFDD’s hallmark shows emerged: Deaconlight Serenade.

***

When Wake Forest moved to Winston-Salem in 1956, WFDD followed. From 1956 to 1991, the station occupied a significant portion of the third floor of Reynolda Hall. It was in those hallowed halls where Deaconlight saw its heyday.

Over two decades after Jack Thomas graduated from Wake Forest College in 1952, a man by the name of Paul Ingles became involved with WFDD as a sophomore.

“I don’t remember having any knowledge of WFDD until we were all packing up to go back home at the end of that freshman year of 1975,” Ingles said.

He credits one late-night party in the Kitchin dormitory as his WFDD awakening.

“We were rocking out, and I said ‘What is that?’”

Ingles’ friend answered: “What else? WFDD!”

Someone along the hall relayed that students could get involved if they took the required radio practicum. In the fall of 1975, Ingles took the class and quickly made friends with upperclassmen involved in the studio, including fellow lifelong journalist Steve Pendlebury, whom he now describes as a close friend of 50 years.

At that time, there were two shows at WFDD hosted exclusively by Wake Forest students: Renaissance, which ran from 7 a.m. to 9 a.m., and Deaconlight, the late-night show that began at 11 p.m. each night and served as Ingles’ introduction to the station. Renaissance was a newer production that offered a prime opportunity for student hosts to reach an audience across the Piedmont Triad during “drive time,” as Ingles calls it, when radio stations receive the most listeners during the morning commute.

“The only stipulation for [Renaissance] was that it not be rocking as hard as Deaconlight rocked, so you had to pick acoustic artists and keep it kind of mellow,” Ingles recalled.

At that time, Pendlebury was the host of Renaissance. Following his enrollment in the radio practicum class, Ingles quickly began accompanying Pendlebury in the studio during the show.

“Sometime in the fall, after I’d only been in [the radio practicum] class for a week or two, Steve let me sit with him,” Ingles said, “And I never left.”

After passing the on-air announcing test that required pronouncing and memorizing various classical composers due to the show’s daytime classical content, Ingles was primed to take over a Deaconlight slot. Beginning in the fall of 1976, he began hosting the Sunday night Deaconlight every week until his graduation in May 1978. On air, he was known mainly for his fondness for Southern California rock artists like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell.

“Everybody leaned in one direction or the other [music wise],” Ingles said, “It was an environment where the student staff was like hanging out at your best friend’s house because everybody was sampling music, the records came in for free and they’d pile up in the student station office where people would just sit there listening for the first time to great albums.”

While the studios created a sense of community for Ingles, working at WFDD wasn’t all fun and games for the students involved.

Under the leadership of Dr. Julian Burroughs, the station’s first non-student manager and a former classmate of Thomas’s on the old campus, WFDD became the first NPR affiliate station in North Carolina in 1970. As a result, students like Ingles were given the opportunity to develop radio journalism skills at a professional-level station with a 36,000-watt transmitter that reached dozens of counties across North Carolina.

After graduating from Wake Forest in 1978, Ingles moved to Charlotte and worked as a news reporter for an AM radio station, a moderator for a local TV news station, a sports reporter for a second AM station and, finally, a program director for a small classic rock station.

Ingles saw lots of parallels between his role at the classic rock station and WFDD.

“We turned [that station] into classic rock radio, which played a lot of the rock bands and the album cuts,” Ingles said, “And that’s what we were doing at WFDD on our own as students.”

After his self-described “good luck streak” ended with the sale of that station in Charlotte, Ingles moved to Albuquerque, N.M. where he worked as a guest announcer, then Cleveland, Ohio, in classic rock again. He then moved back to Albuquerque where he eventually landed a role as a production director for the NPR affiliate associated with the University of New Mexico.

Following his exit from public radio in 2002, Ingles began working as a freelance audio reporter for news and music-related stories. He also began hosting a self-made podcast called “Peace Talks Radio,” which continues today. In October 2023, he started broadcasting his own internet radio station from his garage with a self-established goal to never repeat a song until the total number reached 10,000.

“[The station] is Deaconlight 20 hours a day and two hours a day we play ‘Peace Talks Radio’ episodes and two hours a day we play some of my music documentaries,” Ingles said. “I want to live the dream of making a radio station that sounds like Deaconlight.”

***

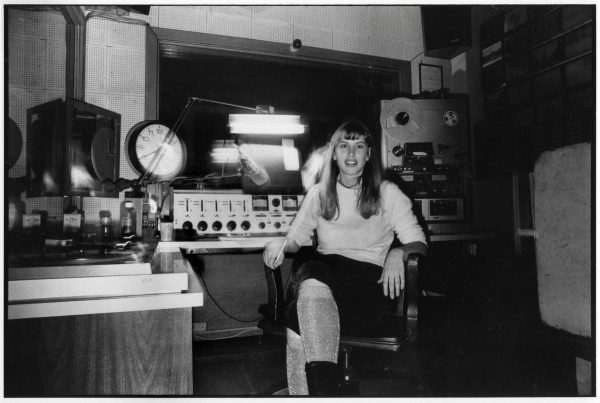

As Paul Ingles began his senior year in the fall of 1977, another WFDD student legend, DD Thornton, arrived at Wake Forest as a freshman.

A Winston-Salem area native, Thornton’s ties to Deaconlight were firmly rooted by the time she arrived on campus a year earlier than scheduled, beginning her freshman year as her friends were starting their senior year of high school.

“You got to go back to when I was in high school,” Thornton said. “I used to listen to Deaconlight every night, or most every night, when it came on at 11 o’clock.”

Despite her love for Deaconlight, Thornton wasn’t initially interested in radio as a career.

“My freshman year, I wasn’t thinking so much about Deaconlight,” she said. “I was thinking about becoming a lawyer or something.”

Yet, the pull toward radio was strong and Thornton couldn’t stay away. After enrolling in the radio practicum course and passing the announcing test, she hosted her first-ever Deaconlight show on Dec. 13, 1977. In the fall of 1978, Thornton discovered the new wave band DEVO.

“After [playing the first DEVO song], I just started getting more interested in all this new stuff coming in,” she remembered.

In time, students began playing new wave bands regularly on Deaconlight, particularly on Fridays and Saturdays when the show ran until 3 a.m. While they were initially met with complaints, there were soon listeners calling in with requests for more, Thornton recalls. A new era had begun at Deaconlight, but it quickly came crashing down.

Burroughs, the aforementioned WFDD faculty advisor, decided to retire from his role at the station at the conclusion of the 1980-81 school year. Around the same time, student announcers hosted their first-ever fundraising drive for the station, raising around $20,000 to support WFDD’s operations and programming.

In the fall of 1981, a new station manager named Pat Crawford arrived. In November, just after student members held their second fundraising drive, it was announced that Deaconlight would be taken off the air by the end of the year.

Crawford said the cancellation of Deaconlight was unfortunate collateral damage in the station’s quest toward professionalization. WFDD had to adopt a program schedule consistent with the network brand and focused on a much larger audience.

“I completely understand why the students initially were not happy with my decision,” Crawford said.

Thorton, however, attributes this to Crawford’s dislike of the type of rock music students played on the show.

“He says there are only three types of art and music: classical, folk and jazz. Rock was, in his mind, not art,” Thornton said.

Crawford, who has worked at the NPR affiliate WUWF radio in Florida since departing WFDD, denied in clear terms that he ever said anything along those lines, finding the accusation preposterous.

“I can be accused of many things, but being a musical snob isn’t one of them,” he said.

Crawford also said that he loves rock music and rock documentaries “to this day.”

Back on campus in 1981, students voiced their disagreement with the decision. More than 600 signatures were collected in a petition organized by students, and opinion pieces were published in the Old Gold & Black student newspaper.

According to his WUWF biography page, Pat Crawford left his position at WFDD in 1982. But the decision was final. On Dec. 27, 1981, DD Thornton hosted the last ever Deaconlight broadcast.

***

As a student at Reynolds High School in the late 70s and early 80s, Paul Garber recalls listening to Deaconlight regularly for its unique sound.

“In the South, we had really regimented, formulaic radio [that] didn’t really break the mold very much,” Garber said. “Deaconlight completely broke the mold. They didn’t care about the mold. There was no mold.”

By the time he arrived at Wake Forest in 1982, however, Deaconlight was gone and student flexibility at WFDD had been drastically reduced. A new club, the ongoing student-run station known as WAKE Radio, was formed in its place.

Garber wasn’t part of the station’s founding but recalls those who faced an uphill battle when it came to WAKE Radio’s establishment.

“It was a situation where [students] needed to make a strong argument as to why there needed to be a breakaway station because Wake Forest already had a station,” Garber said.

Following the university’s approval, WAKE Radio was officially formed and broadcast on a local AM band beginning in 1983. Today, the station broadcasts from the internet, and Garber, who is a reporter for WFDD, is the club’s faculty advisor.

“The goal is that I do as little as possible,” Garber said. “Because I really strongly believe in the student-run ethos of the station.”

One of the student leaders on this year’s WAKE Radio executive board is senior Rachel Gauthier, the assistant station manager. Gauthier joined WAKE Radio at the beginning of her freshman year in 2020. It was WAKE Radio that provided her with a sense of community at a time when little else was happening around campus amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

“There was not a lot happening on campus social life-wise, it was kind of dead compared to how it is now,” Gauthier recalled. “I still wanted to have things to do and look forward to every week. As someone who’s always really loved listening to music and playing music, WAKE radio kind of seemed like the perfect fit for me.”

Since then, aside from her one semester abroad, Gauthier has maintained her 8 p.m. Friday showtime. While some people make themes for each of their shows, Gauthier said she tends to keep hers “pretty eclectic.” In addition to community and friendships, Gauthier sees her shows as a time to decompress.

“I can go into the studio, play what I want, talk about what these songs mean to me [and] decompress for an hour,” she said. “Having this showtime is helpful for me to work through stuff.”

Gauthier has been on the WAKE Radio executive board since her sophomore year, having served as the publications manager and the music director before assuming her current role as assistant station manager.

Over the years, Gauthier’s involvement and leadership in WAKE Radio have allowed her to watch the club flourish.

“My freshman year there were a lot of blank showtimes,” Gauthier said, “This year we’ve had to develop a mechanism to make sure people are showing up to their shows on time because there are more people who want to have a show on WAKE Radio than there are currently showtimes.”

When considering the growth of WAKE Radio over the past four years and its constancy in the 41 years since its founding, it’s clear that the club has offered students a space to be undeniably themselves. Students have free reign over what they choose to play (except the required three “ad” songs per show) and events like semesterly concerts allow space for student hosts to gather in community and student musicians to shine.

***

Deaconlight was pulled off the air nearly 43 years ago. Its loss was felt across campus and the community and, for many, the opportunities the show provided were pivotal in embarking upon a career path. Today, despite the show’s cancellation, the Deaconlight shines on.

On Facebook, DD Thornton, Paul Ingles and other Deaconlight alumni moderate the Deaconlight Virtual Music Bar group, which was founded on December 27, 2007– exactly 26 years after Thornton hosted the final Deaconlight broadcast. As of publication, the group boasts more than 1,300 members who share posts like videos of live performances and memories from their Wake Forest days.

On campus at Wake Forest, WAKE Radio alum Paul Garber teaches a radio journalism course and watches from a distance as dozens of WAKE Radio student hosts plug in their phones and queue up Spotify playlists each week. Records, cassette tapes, CDs, show titles and leaders have come and gone, but the music remains.

This story was originally published on Old Gold & Black on April 29, 2024.