Queer people in the South are increasingly pushing back against a wave of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. However, queer communities thrive in the South by building support systems among each other to resist these legislative attacks and create safe spaces.

The laws are a part of a broader legislative trend across the United States, as the American Civil Liberties Union tracked a total of 533 anti-LGBTQ+ bills nationally in 2024.

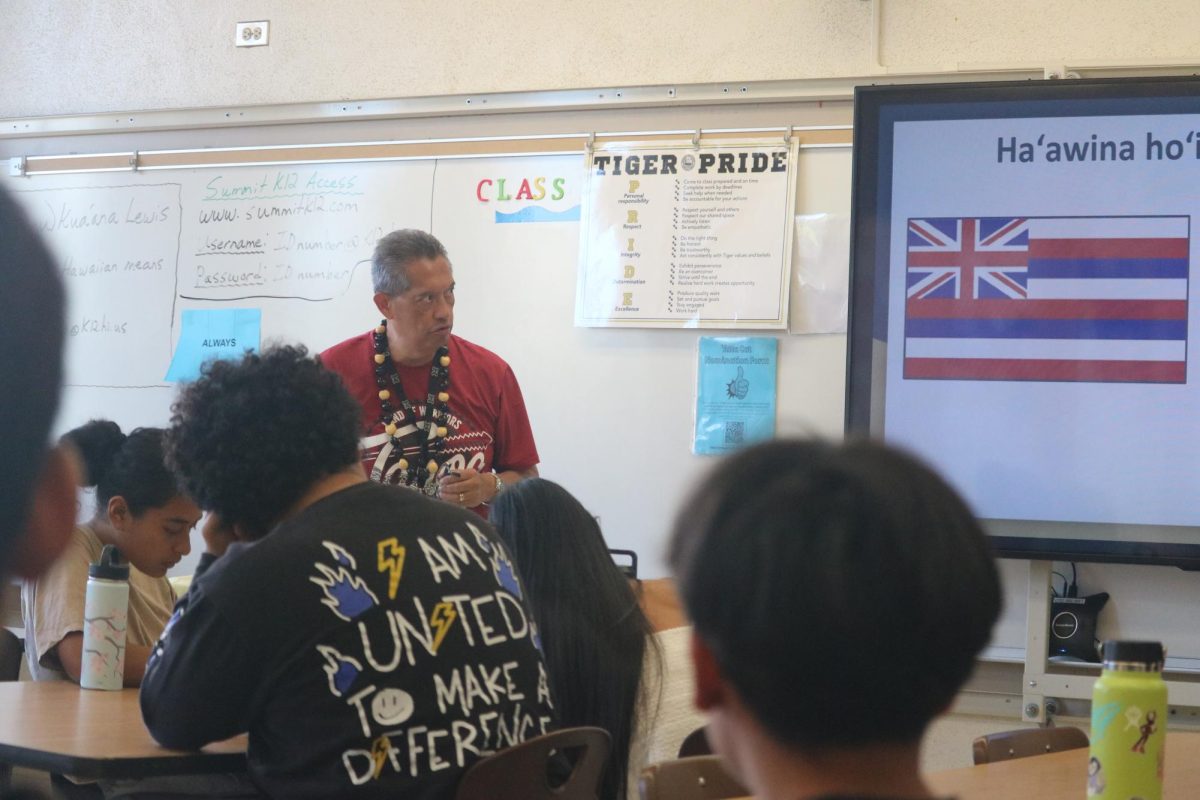

The South houses 36% of the United States’ adult LGBTQ+ population, more than 5 million people, according to USA Today. The region also possesses the most hostile laws and policies affecting LGBTQ+ people. In 2024, the ACLU tracked 40 anti-LGBTQ+ bills in Tennessee, and 14 passed while Governor Bill Lee has signed five into law. Most commonly, these bills targeted students, educators and healthcare for minors.

The Tennessee Equality Project advocates for LGBTQ+ rights in Tennessee by lobbying local government and state legislators. Additionally, the organization provides educational workshops and annually hosts Boro Pride in Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Bean Chapman, who uses they/them pronouns, works as a TEP Chair and a policy analyst for Knox, Anderson and Blount counties. Chapman has three main goals: to advocate for beneficial policies, challenge harmful ones and speak out for queer youth.

Chapman moved from Ohio in 1999 to attend the University of Tennessee for graduate school, which presented new challenges for them and their gender, as they never enjoyed being called “Mrs” or “Ma’am.”

“Sitting silently holding a 3-inch rainbow flag or wearing a rainbow lapel pin is a radical act of protest here,” Chapman said. “So much that the legislature is trying to outlaw them in schools and government buildings.”

The resistance to even the smallest symbols of allyship reflects the broader challenges faced by queer individuals in the South.

Chapman believes abandoning the fight or writing off the South as a lost cause only exacerbates the divide. They found that stigma about the South, weaponized religion and the lack of progressive political support in rural areas became the biggest challenges in their experience.

“Hearing the refrain that we aren’t worth fighting for because we choose to live here isn’t helpful for us, or them,” Chapman said. “More LGBTQ+ people live in the Southeast than any other region, and we have been the bellwethers for what’s to come.”

Another organization at the forefront of queer acceptance in Tennessee is Nashville Pride. Brady Ruffin, who uses he/him pronouns, serves on the Board of Directors, and his mission is to elevate the voices of queer members in the South by creating safe spaces, telling stories and fostering connections. Ruffin emphasized that one of the most common misconceptions about being queer in the South is that it is only hardship and suffering. He first attended Nashville Pride in either 2015 or 2016, and described it as a transformative experience.

“[I]t was the first time I saw such a vibrant and unapologetic celebration of queer joy and livelihood — particularly in the South of all places,” Ruffin said. “The place I’ve always called home and felt comfortable [in], but still a little uneasy about my ability to be fully gay.”

Ruffin said he would still choose to live in Nashville, Tennessee, even if he could live anywhere he wanted. While the queer community faces unique challenges in the Bible Belt, they also possess a profound source of resilience, creativity and a deep sense of community, he said.

One of the unique challenges Ruffin faced was navigating spaces where his queerness felt like a liability, particularly in rural areas. To build relationships and gain trust, he had to mask his identity. Denying his queerness to connect with others felt like shrinking parts of himself. He knows that other queer members feel similarly, and the experience can be exhausting.

“Southern queer folk are some of the most resourceful, unapologetic and loving people I have ever met,” Ruffin said. “ … We’re your neighbors, brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles, family members … The only seemingly different thing about us, the queer community, is that we are viewed differently because of who we love.”

Ruffin does not see the queer community in the South going anywhere, describing it as more unified and resilient than ever.

During 2024, Nashville Pride experienced a record-breaking 125,000 people in attendance.

Elizabeth Cannan-Knight, who uses she/they pronouns, is the president of MTSU’s LGBTQ+ and ally organization — MT Lambda. Cannan-Knight believes the community is a vital part of queerness because of the constant fear of government suppression.

Cannan-Knight recalled an experience that personifies what being queer in the South is like. One time, she was forcibly removed from a bus stop bathroom by security.

She was in line at the women’s bathroom when someone “clocked” her as being transgender. Even after she showed the woman her ID with an “F” gender marker on it, the woman left to get security. Cannan-Knight tried to continue to use the restroom, but she was stopped midway by security slamming on the bathroom door. She left the bathroom stall and showed the security guard her ID. He insisted she needed to leave, and he forcibly escorted her out.

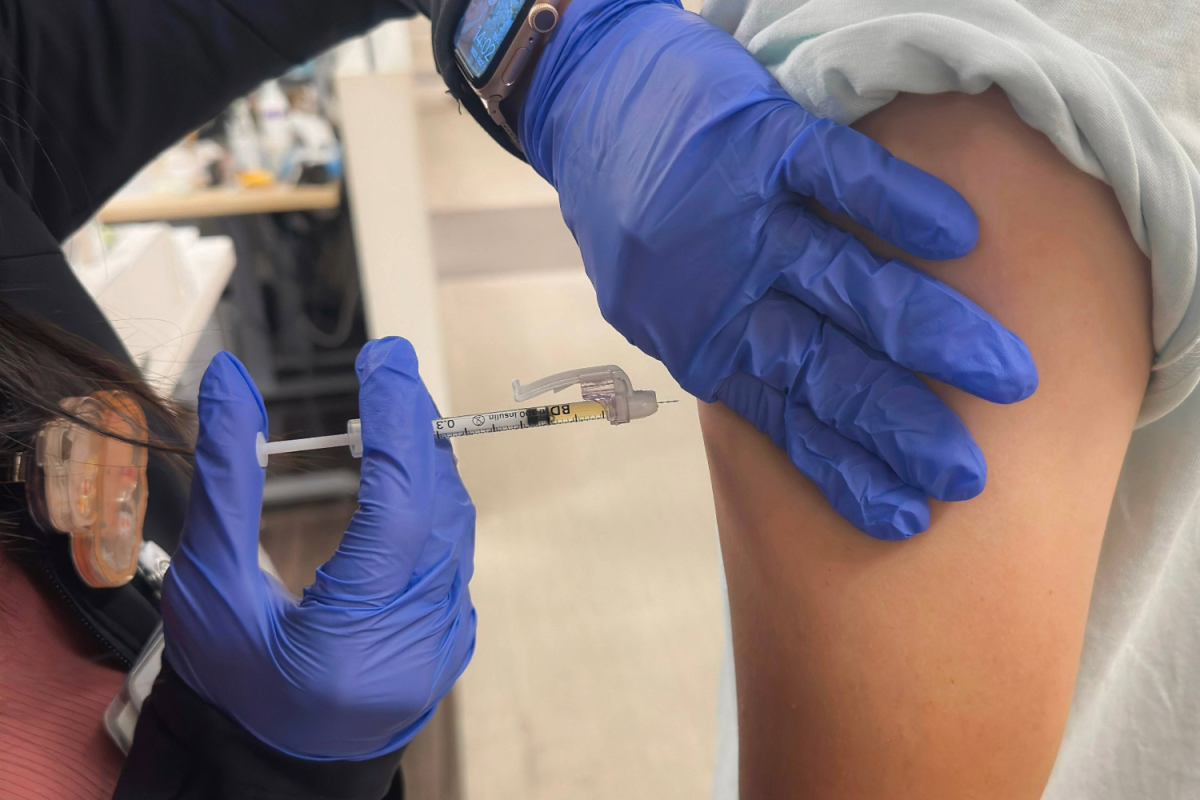

“The primary challenges for queer and trans people, specifically in the South, are legal challenges, and these are what differentiates Southern states from other states,” Cannan-Knight said. “Trans youth are banned from getting gender-affirming care and accessing the bathroom of their gender identity, and trans adults face barriers to proper identification and discrimination protections which can put them in increased danger, especially from law enforcement.”

Cannan-Knight explained that while fear from these experiences leads to poor mental health, it can also lead to a stronger community bond.

Since queer people cannot rely on government institutions in the South, they form support systems of chosen families and mutual aid.

“Most legislation only affects children right now, but we are starting to see an increase in potential legislation that could affect adults as well — bathroom bans, removing anti-discrimination protections, targeting DEI programs, blocking access to proper identification, etc.,” Cannan-Knight said.

This story was originally published on MTSU Sidelines on April 16, 2025.