They call her “Na’cho.”

From underneath the rim of a shiny black S1 helmet that glitters in the outdoor basketball court’s bright floodlights, she silently observes the pattern of her teammates’ movements. Her shoulder-length hair, done up in finger-wide locs, frames her face.

At this practice, no one has completed the obstacle course. The skater who went before her was knocked out of bounds halfway through.

On the sharp blow of the coach’s whistle, Na’cho kicks into gear.

The obstacle course, consisting of two jagged lines of six skaters, moves back and forth like targets in a carnival game; darting from side to side, never twisting or turning their bodies away from their opponent.

Na’cho skilfully moves past her first obstacle, then carefully side steps the next on the toe stops of her quad skates past the opening the third skater makes.

To the frenzied strumming of electric guitars and bass of 90s alternative rock thundering in the background, she swiftly and expertly dodges her obstacles and clears the course to the cheering of her teammates waiting on the sidelines.

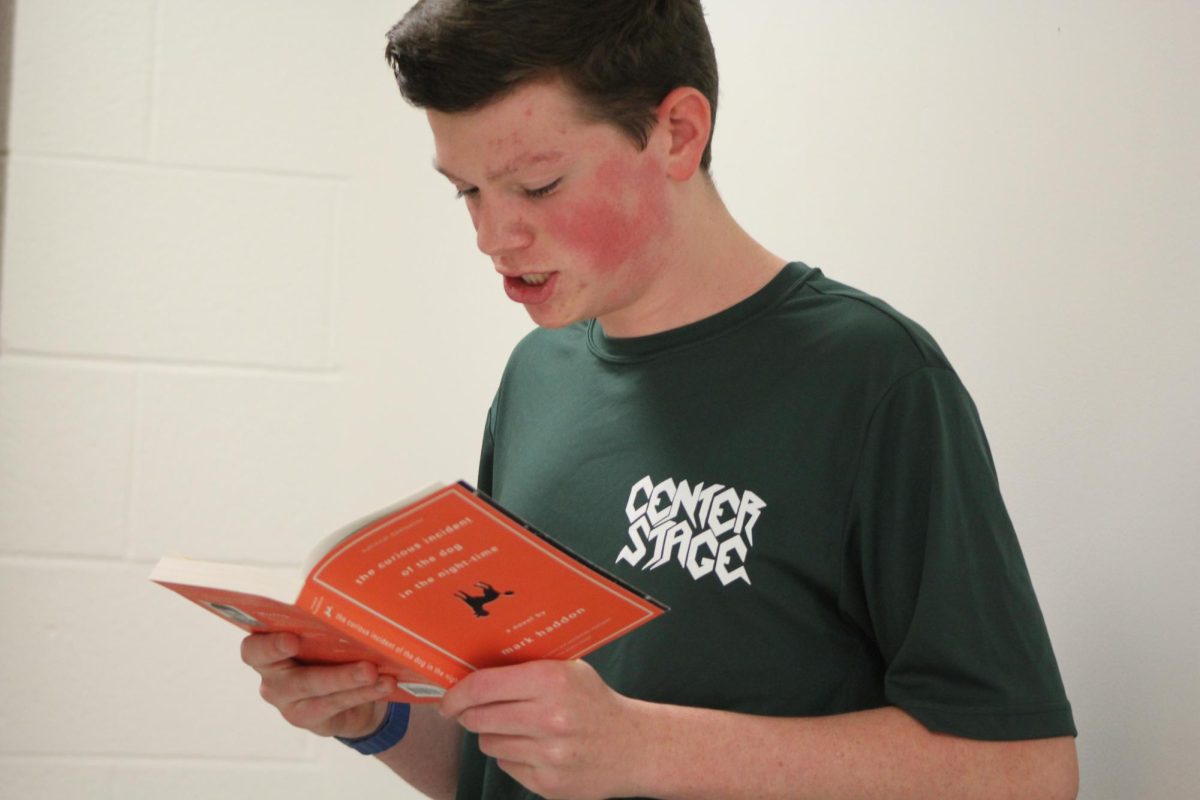

![(L-R) Manuel Grimaldo, Alie Quistberg, Jenn Lee, Elise Vu, Cynthia Beers, Alma Grimaldo and Keiana Daniel line up at Junipero Beach Sports Center in Long Beach on Saturday, April 19. Founded in 2014 and named after a Sublime song, Badfish is one of four roller derby leagues representing the South Bay. [Erica Lee | Warrior Life]](https://eccunion.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Lee_KDPort-1015_EDIT-600x400.jpg)

As she flashes them a broad grin, a black mouth guard carefully fitted over her teeth, the lapels of her black zip-up hoodie fluttering in the breeze like a cape, Na’cho makes a triumphant victory lap before returning to the line for another round.

By night, Na’cho Luckiday is the indomitable jammer and blocker of the Badfish Roller Derby League.

By day, she is Keiana Daniel, the student success coordinator for the Black Student Success Center at El Camino College.

Since 2018, Daniel, 36, has led the growth and development of two communities.

One them is the Black Student Success Center, a support system as ECC students navigate community college life in pursuit of their academic and personal goals.

The other are the skaters of Badfish, a pool of new talent and seasoned pros from all walks of life who come together to practice and compete against other roller derby leagues from across the state and beyond.

The United Skates of America

Back in the 90s, long before she became “Na’cho Luckiday,” Keiana Daniel was just a girl growing up in Southern California who loved books and sports. While she calls Riverside “home,” her schooling would take her to Norwalk, La Habra, Cerritos and Long Beach.

She played soccer, volleyball and was even on a swim team.

“Athletics have always been a big part of my life,” Daniel said. “So is reading, still does.”

Like many girls growing up in the 90s, Daniel found escapism in fantasy novels and the American Girl books, a series of historical fiction stories based on a line of dolls.

Addy Walker, the courageous 9-year-old who fled to freedom on the Underground Railroad, was her favorite character.

“There’s this resilience in her story that really just made me excited to see her achieve something,” she said.

While she wouldn’t know it yet, reading Addy’s stories where she got to attend school, make friends and even have a birthday celebration as a free girl in Philadelphia lit a spark in Daniel. That one day, she’ll grow up to help others find their potential and achieve their goals in academics and more.

In the meantime, Daniel was an elementary school student learning how to roller skate.

Her dad would take her and her sister to Skate Depot in Cerritos for lessons. Skate Depot, which was featured in the 2018 documentary “United Skates” about African-American roller skating culture, closed in 2014.

Daniel’s first pair of skates was a rental.

“My parents’ rule is, ‘try something out. If you really love it, then we can invest,” Daniel said.

When she was 10 years old, she graduated to a pair of black Reidell quad skates with red wheels. These would eventually be the first skates she would use at a roller derby practice over a decade later.

Cut to 2016.

After graduating with a master’s degree in linguistics at California State University, Long Beach, Daniel returned to work with their TRiO Talent Search program, which helps low-income and first-generation high school students from Long Beach and the surrounding communities go to college.

One day, a coworker offered to take her to a roller derby practice after work.

It was for Badfish, a local league the coworker skated with under the name “Necronancy.”

“They [skaters] were just like these superstars,” Daniel said. “Just watching them blow through a warm-up was both intimidating and inspiring.”

In her mid to late-twenties, she had a desire to be just like those skaters.

“And so, it was just like that, I wanted to be like them,” Daniel said.

“Noise, color, body contact”

Roller derby’s roots go back to 1930s Chicago.

That was when Leo Seltzer, a one-time movie theater owner from Oregon, made the career switch to capitalizing on one of the biggest fads sweeping the nation at the time: endurance contests.

Flagpole sitting, walkathons and dance marathons gave Americans an escape from the drudgery of the Great Depression. Some could even win money if they stuck it out long enough and outlast their competition.

His latest venture wouldn’t be any different.

After reading an article in “Literary Digest” about how 90% of Americans have tried roller skating, Seltzer decided to cash in on these early ultramarathons by combining the two.

It worked.

Twenty thousand people packed the Chicago Coliseum to watch as two teams, consisting of a man and a woman, attempted to skate 57,000 laps around a flat track at the first-ever Transcontinental Derby on Aug. 13, 1935.

When attendance began to slow down two years later, Seltzer needed to inject some fresh blood if he hoped to continue bringing in the crowds.

That was when sportswriter Damon Runyon suggested spilling blood.

Introducing full-contact proved to be a monumental success.

Like professional wrestling today, roller derby in the 1930s to the 1970s drew in the crowds with violence and over-the-top theatrics. Players were encouraged to shove, hit, headlock and even get into fist fights with their opponents.

There were even accusations that some matches were rigged.

“Noise, color, body contact,” Seltzer said in a 1971 article for The New York Times when asked to describe roller derby’s appeal.

But by 1973, Seltzer’s son Jerry had shut down the roller derby empire his dad had built, citing high maintenance and travel costs. Because the elder Seltzer had owned all the teams in the league, they had disappeared.

There were attempts to revive roller derby in the 80s and 90s.

But roller derby wouldn’t experience a full-blown resurrection until the early 2000s.

That was when a group of women in Austin, Texas, decided to bring back the sport but with a feminist bent. This time, the teams were all-women with a strong DIY culture and elements borrowed from the Austin drag scene.

According to the Women’s Flat Track Derby Association, there were currently 413 member leagues spread across six continents by 2024.

Whip It

Although they are not a WFTDA-ranked league, Badfish Roller Derby follows their rules and regulations.

The rules of roller derby are simple.

A roller derby bout consists of two 30-minute periods. Active game play during those periods is called “jams,” which can last up to two minutes.

Each team can have up to five skaters, four blockers and a jammer.

The jammer, who wears a helmet cover with a star, scores points by passing the blockers on the opposing team and making a successful lap around the track.

The team with the most points at the end of the game wins.

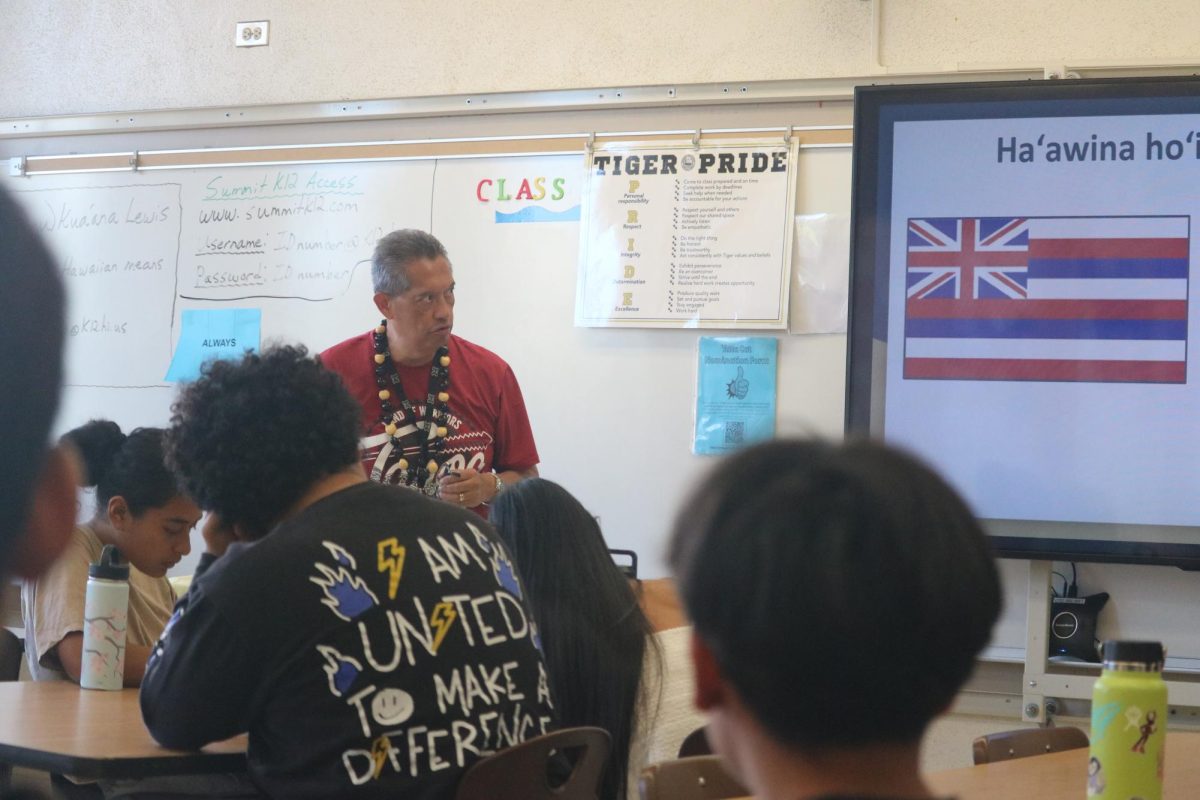

Founded in 2014 and named after a Sublime song, Badfish is a flat track roller derby team from Long Beach. They are one of four roller derby leagues based in the South Bay.

Flat track roller derby refers to the flat oval track on which skaters roll.

This is in contrast to banked track roller derby, which takes place on a slanted track and is ingrained in pop culture with movies such as 2009’s “Whip It” and 2020’s “Birds of Prey.”

Banked track also increases the chances of injury from falling out of range during bouts.

Not that flat track derby doesn’t come with its own risks.

During a scrimmage in 2018, Daniel lost a toenail.

“They somehow convinced me to be a jammer,” she said. “And I lost a toenail that day.”

To be fair, she had played as a jammer during practice. Her teammates had seen her incredible dodging skills and knew she could do it.

“It really pushed me out of my comfort zone,” she said. “I laughed about it later. It’s fine, toenails grow back.”

Breaking Barriers

“There’s no such thing as an average day in the Center,” Daniel said.

A day at the Black Student Success Center can range from a “giggle-fest” where staff and students bond over upcoming events and share and celebrate their accomplishments. Other days, Daniel can be seen showing around high school students who plan on enrolling at El Camino. And other days, the mood is more somber.

“The last few weeks, there’s been more therapy referrals than I’ve had in the past,” she said.

The center is a hub for the college’s student athletes, who are gobsmacked that their mentor plays just as hard and lifts as hard as they can.

“Last semester, I got challenged in person with a football player,” Daniel said. “We went toe-to-toe to see how many [repetitions] we can do. It was very crazy.”

As one of the founders of the Black Student Success Center, Daniel’s heart and soul went into the creation of a community space where El Camino’s Black students can thrive.

“She’s passionate, she is very student-centered,” Chris Hurd, the Student Equity and Achievement counselor and Daniel’s colleague said. “She is someone who fights fearlessly for the best interest of her students.”

There’s even a personal touch with two pothos cuttings at the front desk. These came from Daniel’s own plants at home, which she shares with her wife of two years and their tiny box turtles, Bert and Ernie.

When the BSSC closes for the day at 4:30 p.m., that’s when Daniel starts to make the change to Na’cho.

Tell me, are you a Badfish too?

Badfish practice begins just as the sun sets and the lights surrounding the basketball court at Long Beach’s El Dorado Park burst to life. The air is filled with cheers from the baseball field, where a girls’ softball team plays, and the rush of airplanes landing at the nearby Long Beach Airport.

The time it takes to reach El Dorado Park from ECC is an hour if one takes the Interstate 405.

For Daniel, the commute can take 10 to 15 minutes from her home in the LB area if she takes Interstate 91.

Like Clark Kent, she seamlessly makes the transition to her secret identity.

By the time she rolls up to the basketball court at 7 o’clock, with her gear bag and skates in tow, the thin black and gold glasses she had been wearing at El Camino earlier that day have come off. She’s not Keiana Daniel anymore.

She is Na’cho Luckiday.

Roller Derby names act as a secret identity.

This is where the influence of the Austin drag scene over 20 years ago comes into play.

These skaters come from all walks of life.

They are students, doctors, teachers and business owners. Their derby names reflect their personality. It can be chosen by the skater or someone close to them.

They’re like drag names, but more risqué and violent. Names like Slammin De Beers. Llama Trauma. Esmay Hurt. Kandi The Kid. Malice in Wonderland.

In the case of Na’cho Luckiday, her name came from brainstorming ideas with a skater who went by “Mandatory Beat Down.”

“We tried a play on my actual name because it’s kind of like Keanu Reeves from The Matrix,” Daniel said. “We tried that and we were like, ‘yeah, it doesn’t really give derby.’”

On an average night, there can be up to 40 skaters practicing in one of the two basketball courts. Some skaters have been with Badfish since the beginning.

Others come from other leagues and teams. At least three once skated for Beach Cities Roller Derby, a WFTDA league that disbanded during the pandemic.

“We have a comradery that is unique to the area because we have had roller derby here for so long and people who have played for so long,” Shayna “Pigeon” Meikle said.

Once in charge of Beach Cities Roller Derby, she is also owner of Pigeon’s Skate Shop in Long Beach as well as Pigeon’s Roller Rink.

“That’s the beautiful thing about roller derby. There are so many reasons it draws people in… from finding social groups to getting athletic discipline to finding happiness again. The list goes on,” Meikle said.

The Badfish skaters split off into two practice groups.

The beginners are known as the “guppies,” skaters learning basic skills and the rules of roller derby. To move on to the next group, known as the “school,” they must pass an assessment test.

This week, the school is practicing for an upcoming bout that will be held in Corona.

“We have to travel everywhere for our games because our track is too small,” Badfish President Cynthia Beers said.

The basketball court that serves as a makeshift roller derby track measures 90 feet by 60.5 feet. There’s not enough room for the referee to stand. There’s not even room for spectators.

The lack of a home track invites the opportunity for the Badfish Roller Derby team to get out of the fenced-in confines of their practice space.

“We went to Alaska last year,” Elise Vu, who skates as “Deja Bruise,” said. “Casa Grande, Arizona, Oceanside, San Diego… People in Hawaii want us to go there. So yeah, we get to travel a lot, which is fun.”

Travel costs are covered through fundraising and merchandise sales.

These include sparkly stickers, T-shirts, hoodies and hats. There’s a Pride-themed Badfish shirt featuring their team emblem, an anglerfish with a pair of skated feet sticking out of its toothy maw.

Daniel sticks by Creepy Taco, one of the derby coaches, as the school skaters practice blocking and jamming, simulating gameplay.

“There it is, there it is,” she murmurs, watching as one jammer seamlessly passes the three blockers, who have linked arms and are pivoting to and fro, trying to stop their opposition from scoring.

Then she calls out, “nice, good job!” as the jammer breaks past the wall and proceeds to skate a lap around the track.

When another skater is knocked down, she’s the first to offer comfort and support.

The best trait a roller derby coach can have is leadership.

“When you are a coach, you are a leader and you have to keep your cool and be non-biased,” Meikel said. “If a coach can bring a team together, that’s really powerful.”

Although it’s been two years since she last coached for Badfish, the instinct is still there. Mentoring others doesn’t stop at El Camino. It goes far beyond the confines of the campus.

“Na’cho is very good at explaining things in derby,” Ezra Messer, a studio arts major at ECC who skates as Kandi the Kid, said. “I look up to Na’cho, Na’cho is strong.”

When she is on skates, Daniel can be as swift as a running river or as formidable as a mountain.

“I’m just hitting you in vain,” one Badfish skater said during a blocking exercise. This is when two skaters are paired off. The blocker, assuming a crouching derby stance, has to stop her partner, who is pushing against her, from moving.

Try as she might, the other skater can’t force Daniel to budge.

Daniel sees herself more as a blocker, but has excelled as a jammer.

“This year is different, switching it up,” Daniel said. ‘We’ll see. Maybe I will be a pivot. Who knows?”

This story was originally published on El Camino College Union on May 8, 2025.